Equivalent potential temperature

It is therefore more conserved than the ordinary potential temperature, which remains constant only for unsaturated vertical motions (pressure changes).

Like a ball balanced on top of a hill, denser fluid lying above less dense fluid would be dynamically unstable: overturning motions (convection) can lower the center of gravity, and thus will occur spontaneously, rapidly producing a stable stratification (see also stratification (water)) which is thus the observed condition almost all the time.

Such a saturated parcel of air can achieve buoyancy, and thus accelerate further upward, a runaway condition (instability) even if potential temperature increases with height.

The sufficient condition for an air column to be absolutely stable, even with respect to saturated convective motions, is that the equivalent potential temperature must increase monotonically with height.

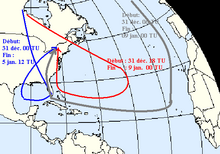

For instance, in a study of the North American Ice Storm of 1998, professors Gyakum (McGill University, Montreal) and Roebber (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) have demonstrated that the air masses involved originated from high Arctic at an altitude of 300 to 400 hPa the previous week, went down toward the surface as they moved to the Tropics, then moved back up along the Mississippi Valley toward the St. Lawrence Valley.

Under normal, stably stratified conditions, the potential temperature increases with height, and vertical motions are suppressed.

Situations in which the equivalent potential temperature decreases with height, indicating instability in saturated air, are quite common.