Ernie O'Malley

Following an abortive attempt to resume his medical studies, O'Malley went to the United States to raise funds for a new nationalist newspaper and spent seven years wandering around the country and Mexico before beginning his writing and coming back to Ireland.

These published works, in addition to his role as a senior leader on the losing side in the civil war, mark him as a primary source in the study of early twentieth-century Irish history and society.

[4][5][6] His was a middle class Catholic family in which he was the second of eleven children born to local man Luke Malley and his wife Marion (née Kearney) from Castlereagh, County Roscommon.

[22][23] O'Malley considered that he received a reasonably good education at the O'Connell Christian Brothers School in North Richmond St, where he "rubbed shoulders with all classes and conditions".

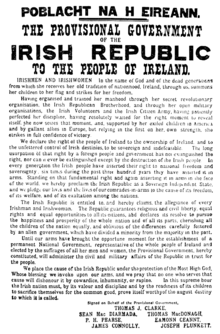

[45] The resentment O'Malley felt at the shooting by firing squad of three of the signatories to the proclamation turned to rage at the execution in early May of John MacBride, whom he knew from visits to the family home.

[59][60] Later, in order to acquire a modern firearm, O'Malley donned his brother's British Army uniform and, armed with a loaded "bulldog .45" revolver, entered Dublin Castle.

[75] From Athlone, where he was planning to seize the magazine fort, an order from Collins in July sent him to help organise brigades in north and south Roscommon on the border with Galway.

[79] Night drilling continued in near silence behind village schoolhouses, but in a number of counties secret organising and planning for raids on RIC barracks to seize weaponry went ahead regardless of risk.

This was an important duty: with minimal help from GHQ, he was to train recruits to become an effective local fighting force against a strong military opponent once the war against the British got under way in January 1919.

[109] This included being badly beaten during his interrogation at Dublin Castle where, as a self-confessed IRA volunteer,[110] he was in severe danger of execution following recent high-profile attacks on British forces.

By late January, a letter from Dublin Castle to senior British military authorities referred to an IRA officer, a "notorious rebel" called "E. Malley", whom they were most anxious to arrest in connection with "many attacks on barracks".

[121][103] In spring 1921 O'Malley chaired a stormy meeting near Mallow at which he advised senior Cork figures that GHQ had ordered the formation of the First Southern Division, in Munster.

[126] He was to complain that his orders to brigade commandants for a coordinated attack on British forces in mid-May, as part of a wider IRA effort to prevent the execution of captured comrades, had not been carried out.

[160][161] That body later established an anti-treaty headquarters staff in which O'Malley became director of organisation and a member of the executive; he was also secretary to the IRA Convention which went ahead on 26 March despite GHQ having banned it.

[163][164] On 14 April, O'Malley was one of the Anti-Treaty IRA officers who occupied the Four Courts in Dublin, an event that helped to widen the split even further prior to the start of the Irish Civil War.

Even in late June O'Malley was planning an attack on Northern Ireland and sent Todd to Cavan to meet local IRA commandant Paddy Smith.

[186] In September 1922, O'Malley pressed Lynch to implement Liam Mellows' proposed 10-Point Programme for the IRA, which would have seen it adopt communist policies in an attempt to secure support from left-wing elements in Ireland.

He joined Frank Aiken (commander of the IRA's 4th Northern Division) and Pádraig Ó Cuinn (quartermaster-general) for a planned assault on Free State positions in Dundalk.

[193] O'Malley also believed that Lynch's strategy of holding a defensive line in the south and locating GHQ in County Cork made no sense:[194][195] a concerted attack on Dublin should have been an early priority.

[198] In late October, O'Malley issued an order that the names of all enemy officers or soldiers who had ill-treated prisoners or been party of Free State “murder gangs” were to be circulated to IRA units with a shoot-on-sight instruction.

[199][200][201] On 4 November 1922, O'Malley was captured after a shoot-out with Free State soldiers at the family home of Nell O'Rahilly Humphreys, 36 Ailesbury Road, in the Donnybrook area of Dublin, which had been his headquarters for six weeks.

He also proposed a motion, passed unanimously, that IRA members must refuse to recognise courts in the Free State or Six Counties for charges relating to actions committed during the war or to political activities since then.

[251][252] O'Malley was one of two Irish republicans, the other being Ambrose Victor Martin, to have cooperated with the Basque and Catalan nationalists resident in Paris, then exiled from the Spanish dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera.

[251] The following excerpt from a letter from O'Malley to Harriet Monroe, dated 10 January 1935, provides an autobiographical summary of the years 1925–1926: I went to Catalonia to help the Catalan movement for independence; I studied their folklore and cultural institutions.

For eight months in 1928 and 1929, he and Frank Aiken toured the east and west coasts of the USA on behalf of de Valera's plan to raise funds for the establishment of the new, independent pro-republican newspaper, The Irish Press.

[45] In June of that year, it was noted in the Dáil that he was rumoured to be coming back into public life as chief of staff of the Volunteer Force created by the government in April.

[297] Todd Andrews stated that O'Malley had "taken part in more attacks on British soldiers, Black and Tans and RIC than any other IRA men in Ireland"; yet while admired, he was not generally liked.

[298] O’Malley's good friend Tony Woods, who had been in the Four Courts, disapproved of The Singing Flame (which he incorrectly attributed to Frances-Mary Blake) and considered O'Malley "only a third-rate general".

[321] In an article in The Irish Times in 1996, the writer John McGahern described On Another Man's Wound as "the one classic work to have emerged directly from the violence that led to independence", adding that it "deserves a permanent and honoured place in our literature".

[333] O'Malley also gathered ballads and stories from the revolutionary period; and during World War II, he noted down over 300 traditionary folktales from his native area near Clew Bay in Mayo.