Ernst Rüdin

[2] From 1907, Rüdin worked at the University of Munich as an assistant to Emil Kraepelin, the highly influential psychiatrist who had developed the diagnostic split between 'dementia praecox' ('early dementia' – reflecting his pessimistic prognosis – renamed schizophrenia) and 'manic-depressive illness' (including unipolar depression), and who is considered by many to be the father of modern psychiatric classification.

[5] Fears of degeneration were somewhat common internationally at the time, but the lengths to which Rüdin took them may have been unique, and from the very beginning of his career he made continuous efforts to have his research translate into political action.

[7] Rüdin's data did not show a high enough risk in siblings for schizophrenia to be due to a simple recessive gene as he and Kraepelin thought, but he put forward a two-recessive-gene theory to try to account for this.

[10] Nevertheless, Rüdin pioneered and refined complex techniques for conducting studies of inheritance, was widely cited in the international literature for decades, and is still regarded as "the father of psychiatric genetics".

The Institute incorporated a Department of Genealogical and Demographic Studies (known as the GDA in German) – the first in the world specialising in psychiatric genetics – and Rüdin was put in charge by overall director Kraepelin.

These included Eliot Slater and Erik Stromgren, considered the founding fathers of psychiatric genetics in Britain and Scandinavia respectively, as well as Franz Josef Kallmann, who became a leading figure in twins research in the US after emigrating in 1936.

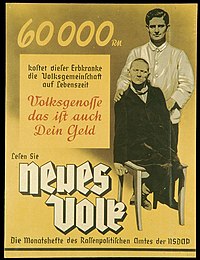

The committee's ideas were used as a scientific basis to justify the racial policy of Nazi Germany and its "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" was passed by the German government on 1 January 1934.

He supported and financially aided the work of Julius Duessen at Heidelberg University with Carl Schneider, clinical research which from the beginning involved killing children.

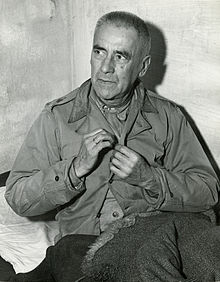

[6][20][24][25] At the end of the war in 1945, Rüdin claimed he had only ever engaged in academic science, only ever heard rumours of killings at the nearby insane asylums, and that he hated the Nazis.

"[citation needed] In 1945, Rüdin was stripped of his Swiss citizenship, which he had held jointly with German since 1912,[2] and two months later was placed under house arrest by the Munich Military Government.

However, interned in the US, he was released in 1947 after a 'denazification' trial where he was supported by former colleague Kallmann (a eugenicist himself) and famous quantum physicist Max Planck[verification needed]; his only punishment was a 500 ℛ︁ℳ︁ fine.

[26] Speculation about the reasons for his early release, despite having been considered as a potential criminal defendant for the Nuremberg trials, include the need to restore confidence and order in the German medical profession; his personal and financial connections to prestigious American and British researchers, funding bodies and others; and the fact that he repeatedly cited American eugenic sterilization initiatives to justify his own as legal (indeed the Nuremberg trials carefully avoided highlighting such links in general).

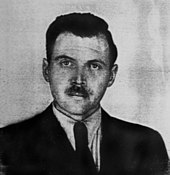

Nevertheless, Rüdin has been cited as a more senior and influential architect of Nazi crimes than the physician who was sentenced to death, Karl Brandt, or the infamous Josef Mengele, who had attended his lectures and been employed by his Institute.

[27] After Rüdin's death in 1952, the funeral eulogy was delivered by Kurt Pohlisch [de], a close friend who had been professor of psychiatry at Bonn University, director of the second-largest genetics research institute in Germany, and expert Nazi advisor on Action T4.