Eros and Civilization

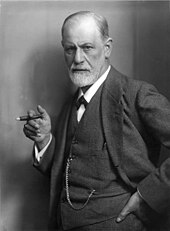

Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (1955; second edition, 1966) is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, and explores the potential of collective memory to be a source of disobedience and revolt and point the way to an alternative future.

Both Marcuse and many commentators have considered it his most important book, and it was seen by some as an improvement over the previous attempt to synthesize Marxist and psychoanalytic theory by the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich.

[2] Marcuse also discusses the views of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller,[3] and criticizes the psychiatrist Carl Jung, whose psychology he describes as an "obscurantist neo-mythology".

[5] Eros and Civilization received positive reviews from the philosopher Abraham Edel in The Nation and the historian of science Robert M. Young in the New Statesman.

"[7] Sontag wrote that together with Brown's Life Against Death (1959), Eros and Civilization represented a "new seriousness about Freudian ideas" and exposed most previous writing on Freud in the United States as irrelevant or superficial.

[9] Tuttle suggested that Eros and Civilization could not be properly understood without reading Marcuse's earlier work Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity (1932).

He credited Marcuse with developing "logically and psychologically the instinctual dynamic trends leading to the utopia of a nonrepressive civilization" and demonstrating that "true freedom is not possible in reality today", being reserved for "fantasies, dreams, and the experiences of art."

[16] Nyberg described the book as "brilliant", "moving", and "extraordinary", concluding that it was, "perhaps the most important work on psychoanalytic theory to have appeared in a very long time.

Celarent suggested that Eros and Civilization had commonly been misinterpreted, and that Marcuse was not concerned with advocating "free love and esoteric sexual positions.

"[21] Discussions of the work in Theory & Society include those by the philosopher and historian Martin Jay,[24] the psychoanalyst Nancy Chodorow,[25] and C. Fred Alford.

Jay suggested that the views of the philosopher Ernst Bloch might be superior to Marcuse's, since they did more to account for "the new in history" and more carefully avoided equating recollection with repetition.

"[26] Other discussions of the work include those by the philosopher Jeremy Shearmur in Philosophy of the Social Sciences,[27] the philosopher Timothy F. Murphy in the Journal of Homosexuality,[28] C. Fred Alford in Theory, Culture & Society,[29] Michael Beard in Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures,[30] Peter M. R. Stirk in the History of the Human Sciences,[31] Silke-Maria Weineck in The German Quarterly,[32] Joshua Rayman in Telos,[33] Daniel Cho in Policy Futures in Education,[34] Duston Moore in the Journal of Classical Sociology,[35] Sean Noah Walsh in Crime, Media, Culture,[36] the philosopher Espen Hammer in Philosophy & Social Criticism,[37] the historian Sara M. Evans in The American Historical Review,[38] Molly Hite in Contemporary Literature,[39] Nancy J. Holland in Hypatia,[40] Franco Fernandes and Sérgio Augusto in DoisPontos,[41] and Pieter Duvenage in Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe.

[40] Hammer argued that Marcuse was "incapable of offering an account of the empirical dynamics that may lead to the social change he envisions, and that his appeal to the benefits of automatism is blind to its negative effects" and that his "vision of the good life as centered on libidinal self-realization" threatens the freedom of individuals and would "potentially undermine their sense of self-integrity."

Hammer maintained that, unlike the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, Marcuse failed to "take temporality and transience properly into account" and had "no genuine appreciation of the need for mourning."

She argued that while Marcuse does not mention pedophilia, it fits his argument that perverse sex can be "revelatory or demystifying, because it returns experience to the physical body".

[42] Farr, Kellner, Lamas, and Reitz wrote that partly because of the impact of Eros and Civilization, Marcuse's work influenced several academic disciplines in the United States and in other countries.

He believed they went beyond Reich and the anthropologist Géza Róheim in probing the dialectical subtleties of Freud's thought, thereby reaching conclusions more extreme and utopian than theirs.

He maintained that Marcuse neglected politics, disregarded the class struggle, advocated "sublimation of human spontaneity and creativity", and failed to criticize the underlying assumptions of Freudian thinking.

[59] The psychotherapist Joel D. Hencken described Eros and Civilization as an important example of the intellectual influence of psychoanalysis and an "interesting precursor" to a study of psychology of the "internalization of oppression".

She concluded that all the esoteric Fruedian theory and endorsements of libertine sexual behavior were ultimately meant only to colorfully illustrate what Marcuse had previously written about concerning the alienating force of the Power Principle.

[63] The philosopher Jeffrey Abramson credited Marcuse with revealing the "bleakness of social life" to him and forcing him to wonder why progress does "so little to end human misery and destructiveness".

[65] The anthropologist Pat Caplan identified Eros and Civilization as an influence on student protest movements of the 1960s, apparent in their use of the slogan, "Make love not war".

[66] Victor J. Seidler credited Marcuse with showing that the repressive organizations of the instincts described by Freud are not inherent in their nature but emerge from specific historical conditions.

[69] The philosopher Richard J. Bernstein described Eros and Civilization as "perverse, wild, phantasmal and surrealistic" and "strangely Hegelian and anti-Hegelian, Marxist and anti-Marxist, Nietzschean and anti-Nietzschean", and praised Marcuse's discussion of the theme of "negativity".

[75] The historian Arthur Marwick identified Eros and Civilization as the book with which Marcuse achieved international fame, a key work in the intellectual legacy of the 1950s, and an influence on the subcultures of the 1960s.

[76] The historian Roy Porter argued that Marcuse's view that "industrialization demanded erotic austerity" was not original, and was discredited by Foucault in The History of Sexuality (1976).

[77] The philosopher Todd Dufresne compared Eros and Civilization to Brown's Life Against Death and the anarchist author Paul Goodman's Growing Up Absurd (1960).

[80] The philosopher James Bohman wrote that Eros and Civilization "comes closer to presenting a positive conception of reason and Enlightenment than any other work of the Frankfurt School.

"[81] The historian Dagmar Herzog wrote that Eros and Civilization was, along with Life Against Death, one of the most notable examples of an effort to "use psychoanalytic ideas for culturally subversive and emancipatory purposes".

"[82] The critic Camille Paglia wrote that while Eros and Civilization was "one of the centerpieces of the Frankfurt School", she found the book inferior to Life Against Death.