Eschatology

Christianity depicts the end time as a period of tribulation that precedes the second coming of Christ, who will face the rise of the Antichrist along with his power structure and false prophets, and usher in the Kingdom of God.

Dharmic religions tend to have more cyclical worldviews, with end-time eschatologies characterized by decay, redemption, and rebirth (though some believe transitions between cycles are relatively uneventful).

[4] The Oxford English Dictionary defines eschatology as "the part of theology concerned with death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of humankind".

The end times are addressed in the Book of Daniel and in numerous other prophetic passages in the Hebrew scriptures, and also in the Talmud, particularly Tractate Avodah Zarah.

The idea of a Messianic Age, an era of global peace and knowledge of the Creator, has a prominent place in Jewish thought, and is incorporated as part of the end of days.

A number of early and late Jewish scholars have written in support of this, including the Ramban,[10] Isaac Abarbanel,[11] Abraham Ibn Ezra,[12] Rabbeinu Bachya,[13] the Vilna Gaon,[14] the Lubavitcher Rebbe,[15] the Ramchal,[16] Aryeh Kaplan[17] and Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis.

[20] However, with beliefs paralleling and possibly predating the framework of the major Abrahamic faiths, a fully developed concept of the end of the world was not established in Zoroastrianism until 500 BCE.

The Bahman Yasht describes: At the end of thy tenth hundredth winter, the sun is more unseen and more spotted; the year, month, and day are shorter; and the earth is more barren; and the crop will not yield the seed.

[21][19] The Gnostic codex On the Origin of the World (possibly dating from near the end of the third century AD) states that during what is called the consummation of the age, the Sun and Moon will become dark as the stars change their ordinary course.

[22] Christian eschatology is the study concerned with the ultimate destiny of the individual soul and of the entire created order, based primarily upon biblical texts within the Old and New Testaments.

[23] In the New Testament, applicable passages include Matthew 24, Mark 13, the parable of "The Sheep and the Goats" and the Book of Revelation—Revelation often occupies a central place in Christian eschatology.

"In the New Testament, Jesus refers to this period preceding the end times as the "Great Tribulation" (Matthew 24:21), "Affliction" (Mark 13:19), and "days of vengeance" (Luke 21:22).

The Book of Matthew describes the devastation: When ye therefore shall see the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet, stand in the holy place, (whoso readeth, let him understand).

"And there will be signs in sun and moon and stars, and on the earth distress of nations in perplexity because of the roaring of the sea and the waves, people fainting with fear and with foreboding of what is coming on the world.

In 1918 a group of eight, well-known preachers produced the London Manifesto, warning of an imminent second coming of Christ shortly after the 1917 liberation of Jerusalem by the British.

Within dispensational premillennialist writing, there is the belief that Christians will be summoned to Heaven by Christ at the rapture, occurring before a Great Tribulation prophesied in Matthew 24–25; Mark 13 and Luke 21.

The difference between the 19th-century Millerite and adventist movements and contemporary prophecy is that William Miller and his followers, based on biblical interpretation, predicted the time of the Second Coming to have occurred in 1844.

Seventh-day Adventists believe biblical prophecy to foretell an end time scenario in which the United States works in conjunction with the Catholic Church to mandate worship on a day other than the true Sabbath, Saturday, as prescribed in the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:8–11).

As his predictions did not come true (referred to as the Great Disappointment), followers of Miller went on to found separate groups, the most successful of which is the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

[52] Several Baháʼí books and pamphlets make mention of the Millerites, the prophecies used by Miller and the Great Disappointment, most notably William Sears's Thief in the Night.

Claims about the significance of those years, including the presence of Jesus Christ, the beginning of the "last days", the destruction of worldly governments and the earthly resurrection of Jewish patriarchs, were successively abandoned.

Watch Tower Society publications also say that unfulfilled expectations are partly due to eagerness for God's Kingdom and that they do not call their core beliefs into question.

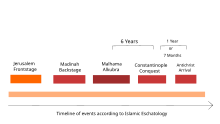

[83][84][85] Sunnis believe the dead will then stand in a grand assembly, awaiting a scroll detailing their righteous deeds, sinful acts and ultimate judgment.

[99] Ahmadis believe that despite harsh and strong opposition and discrimination they will eventually be triumphant and their message vindicated both by Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

There is also the expectation that Selassie will return for a day of judgment and bring home the "lost children of Israel", which in Rastafari refers to those taken from Africa through the slave trade.

[108] The cycle of birth, growth, decay, and renewal at the individual level finds its echo in the cosmic order, yet is affected by vagueries of divine intervention in Vaishnavite belief.

Once Buddha, he will rule over the Ketumati Pure Land, an earthly paradise sometimes associated with the Indian city of Varanasi or Benares in present-day Uttar Pradesh.

Edward Conze in his Buddhist Scriptures (1959) gives an account of Maitreya: The Lord replied, 'Maitreya, the best of men, will then leave the Tuṣita heavens and go for his last rebirth.

Maitreya eschatology forms the central canon of the White Lotus Society, a religious and political movement which emerged in Yuan China.

This end is described in a passage in the Coffin Texts and a more explicit one in the Book of the Dead, in which Atum says that he will one day dissolve the ordered world and return to his primeval, inert state within the waters of chaos.