Establishment Clause

The statute disestablished the Church of England in Virginia and guaranteed freedom of religion exercise to men of all religious faiths, including Catholics and Jews as well as members of all Protestant denominations.

As Virginia prepared to hold its elections to the state ratifying convention in 1788, the Baptists were concerned that the Constitution had no safeguard against the creation of a new national church.

[7] A number of historians have concluded on the basis of compelling circumstantial evidence that, just prior to the election in March 1788, Madison met with Leland and gained his support of ratification by addressing these concerns and providing him with the necessary reassurances.

[23] Other colonies would more generally assist religion by requiring taxes that would partially fund religious institutions - taxpayers could direct payments to the Protestant denomination of their choosing.

During and after the American Revolution, religious minorities, such as the Methodists and the Baptists, argued that taxes to support religion violated freedoms won from the British.

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme Court upheld a New Jersey statute funding student transportation to schools, whether parochial or not.

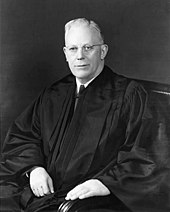

Justice Hugo Black held, The "establishment of religion" clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the federal government can set up a church.

No tax in any amount, large or small, can be levied to support any religious activities or institutions, whatever they may be called, or whatever form they may adopt to teach or practice religion.

Critics of Black's reasoning (most notably, former Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist) have argued that the majority of states did have "official" churches at the time of the First Amendment's adoption and that James Madison, not Jefferson, was the principal drafter.

Another description reads: "line of separation between the rights of religion and the civil authority... entire abstinence of the government" (1832 letter Rev.

Adams), and "practical distinction between Religion and Civil Government as essential to the purity of both, and as guaranteed by the Constitution of the United States" (1811 letter to Baptist Churches).

In both cases, states—New York and Pennsylvania—had enacted laws whereby public tax revenues would be paid to low-income parents so as to permit them to send students to private schools.

It was found that there was no "excessive entanglement" since the buildings were themselves not religious, unlike teachers in parochial schools, and because the aid came in the form of a one-time grant, rather than continuous assistance.

The Supreme Court, in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), upheld the constitutionality of private school vouchers, turning away an Establishment Clause challenge.

The case involved the mandatory daily recitation by public school officials of a prayer written by the New York Board of Regents, which read "Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country".

In Abington Township v. Schempp (1963), the case involving the mandatory reading of the Lord's Prayer in class, the Supreme Court introduced the "secular purpose" and "primary effect" tests, which were to be used to determine compatibility with the establishment clause.

In Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), the Supreme Court struck down an Alabama law whereby students in public schools would observe daily a period of silence for the purpose of private prayer.

In Lee v. Weisman (1992), the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the offering of prayers by religious officials before voluntarily attending ceremonies such as graduation.

In 2002, controversy centered on a ruling by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow (2002), which struck down a California law providing for the recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance (which includes the phrase "under God") in classrooms.

The Supreme Court heard arguments on the case, but did not rule on the merits, instead reversing the Ninth Circuit's decision on standing grounds.

The inclusion of religious symbols in public holiday displays came before the Supreme Court in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), and again in Allegheny County v. Greater Pittsburgh ACLU (1989).

At the same time, the Allegheny County Court upheld the display of a nearby menorah, which appeared along with a Christmas tree and a sign saluting liberty, reasoning that "the combined display of the tree, the sign, and the menorah ... simply recognizes that both Christmas and Hanukkah are part of the same winter-holiday season, which has attained a secular status in our society."

On March 2, 2005, the Supreme Court heard arguments for two cases involving religious displays, Van Orden v. Perry and McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky.

In Van Orden, the Court upheld, by a 5–4 vote, the legality of a Ten Commandments display at the Texas State Capitol due to the monument's "secular purpose".

In the 1964 case McGowan v. Maryland, the Supreme Court held that blue laws which restricted the sale of goods on Sundays (and were originally intended to increase Church attendance) did not violate the Establishment Clause because they served a present secular purpose of providing a uniform day of rest for everyone.