History of the Jews in Estonia

Jews were settled in Estonia in the 19th century, especially following a statute of Russian Tsar Alexander II in 1865 allowed the so-called Jewish "Nicholas soldiers" (often former cantonists) and their descendants, First Guild merchants, artisans, and Jews with higher education to settle outside the Pale of Settlement.

A synagogue was also built in Võru as shown in the records of Estonian Jewish historian Nathan Ganns.

[3] The Jewish population spread to other Estonian cities where houses of prayer (at Valga, Pärnu and Viljandi) were erected and cemeteries were established.

At the end of the 19th century, however, several Jews entered the University of Tartu and later contributed significantly to enliven Jewish culture and education.

[4] Among the Jewish residents of Võro who graduated from the University of Tartu was Moses Wolf Goldberg.

Approximately 200 Jews fought in combat in the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920) for the creation of the Republic of Estonia.

This set the stage for energetic growth in the political and cultural activities of Jewish society.

The kibbutzim of Kfar Blum and Ein Gev were set up in part by Estonian Jews.

The administrative organ of this autonomy was the Board of Jewish Culture, headed by Hirsch Aisenstadt until it was disbanded following the Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1940.

The Jewish National Endowment Keren Kajamet presented the Estonian government with a certificate of gratitude for this achievement.

[5] From the very first days of its existence as a state, Estonia showed tolerance towards all the peoples inhabiting its territories.

For its tolerant policy towards Jews, a page was dedicated to the Republic of Estonia in the Golden Book of Jerusalem in 1927.

The Jewish Goodwill Society of the Tallinn Congregation made it their business to oversee and execute the ambitions of this system.

In Tartu the Jewish Assistance Union was active, and welfare units were set up in Narva, Valga and Pärnu.

Nazism was outlawed as a movement contrary to social order, the German Cultural Council was disbanded, and the National Socialist Viktor von Mühlen, the elected member of the Baltic German Party, was forced to resign from the Riigikogu.

"[7]In February 1937, as anti-semitism was growing elsewhere in Europe, the vice president of the Jewish Community Heinrich Gutkin was appointed by Presidential decree to the Estonian upper parliamentary chamber, the Riiginõukogu.

A relatively large number of Jews (350–450, about 10% of the total Jewish population) were deported into prison camps in Russia by the Soviet authorities on 14 June 1941, where most perished.

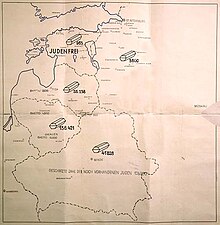

[9][10] More than 75% of Estonia's Jewish community, aware of the fate that otherwise awaited them, managed to escape to the Soviet Union; virtually all the remainder (between 950 and 1000 men, women, and children) had been killed by the end of 1941.

[11] Round-ups and killings of Jews began immediately following the arrival of the first German troops in 1941, who were closely followed by the extermination squad Sonderkommando 1a under Martin Sandberger, part of Einsatzgruppe A led by Walter Stahlecker.

Arrests and executions continued as the Germans, with the assistance of local collaborators, advanced through Estonia.

Unlike German forces, Estonians seem to have supported the anti-Jewish actions on the political level, but not on a racial basis.

Estonians often argued that their Jewish colleagues and friends were not communists and submitted proof of pro-Estonian conduct in the hope of being able to get them released.

[12] Anton Weiss-Wendt in his dissertation "Murder Without Hatred: Estonians, the Holocaust, and the Problem of Collaboration" concluded on the basis of the reports of informers to the occupation authorities that Estonians in general did not believe in Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda and by majority maintained positive opinion about Jews.

In March 1988, as Estonia regained its independence, the Jewish Cultural Society was established in Tallinn, the first of its kind in the former Soviet Union.

The restoration of Estonian independence in 1991 brought about numerous political, economic and social changes.

In support of this a new Cultural Autonomy Act, based on the original 1925 law, was passed in Estonia in October 1993, which grants minority communities, including Jewish, a legal guarantee to preserve their national identities.

[25] In contrast to many other European countries, Estonia's Jewish population peaked only after World War II, at almost 5,500 people in 1959.