Spinoza's Ethics

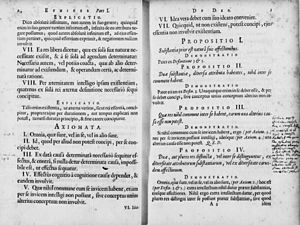

Spinoza puts forward a small number of definitions and axioms from which he attempts to derive hundreds of propositions and corollaries, such as "When the Mind imagines its own lack of power, it is saddened by it",[2] "A free man thinks of nothing less than of death",[3] and "The human Mind cannot be absolutely destroyed with the Body, but something of it remains which is eternal.

He holds the perspective that the conclusion he presents is merely the necessary logical result of combining the provided Definitions and Axioms.

Spinoza claims that the things that make up the universe, including human beings, are God's "modes".

Spinoza attacks several Cartesian positions: (1) that the mind and body are distinct substances that can affect one another; (2) that we know our minds better than we know our bodies; (3) that our senses may be trusted; (4) that despite being created by God we can make mistakes, namely, when we affirm, of our own free will, an idea that is not clear and distinct.

Regarding (1), Spinoza argues that the mind and the body are a single thing that is being thought of in two different ways.

However, we cannot mix these two ways of describing things, as Descartes does, and say that the mind affects the body or vice versa.

Sensory perception, which Spinoza calls "knowledge of the first kind", is entirely inaccurate, since it reflects how our own bodies work more than how things really are.

Spinoza considers how the affects, ungoverned, can torment people and make it impossible for mankind to live in harmony with one another.

In his previous book, Theologico-Political Treatise, Spinoza discussed the inconsistencies that result when God is assumed to have human characteristics.

[16] Spinoza's naturalism can be seen as deriving from his firm commitment to the principle of sufficient reason (psr), which is the thesis that everything has an explanation.

He articulates the psr in a strong fashion, as he applies it not only to everything that is, but also to everything that is not: Of everything whatsoever a cause or reason must be assigned, either for its existence, or for its non-existence — e.g. if a triangle exists, a reason or cause must be granted for its existence; if, on the contrary, it does not exist, a cause must also be granted, which prevents it from existing, or annuls its existence.And to continue with Spinoza's triangle example, here is one claim he makes about God: From God's supreme power, or infinite nature, an infinite number of things – that is, all things have necessarily flowed forth in an infinite number of ways, or always flow from the same necessity; in the same way as from the nature of a triangle it follows from eternity and for eternity, that its three interior angles are equal to two right angles.Spinoza rejected the idea of an external Creator suddenly, and apparently capriciously, creating the world at one particular time rather than another, and creating it out of nothing.

This view was simpler; it avoided the impossible conception of creation out of nothing; and it was religiously more satisfying by bringing God and man into closer relationship.

[17] Spinoza's ideas relating to the character and structure of reality are expressed by him in terms of substance, attributes, and modes.

And in order to express this idea, he then described Extension and Thought as attributes, reserving the term Substance for the system which they constitute between them.

Each Attribute, however, expresses itself in its finite modes not immediately (or directly) but mediately (or indirectly), at least in the sense to be explained now.

And the whole Universe or Substance is conceived as one dynamic system of which the various Attributes are the several world-lines along which it expresses itself in all the infinite variety of events.

[17][21] Given the persistent misinterpretation of Spinozism it is worth emphasizing the dynamic character of reality as Spinoza conceived it.

The moral categories, good and evil, are intimately connected with desire, though not in the way commonly supposed.

[17] Spinoza gives a detailed analysis of the whole gamut of human feelings, and his account is one of the classics of psychology.

It is the passive feelings (or "passions") which are responsible for all the ills of life, for they are induced largely by things outside us and frequently cause that lowered vitality which means pain.

At the lowest stage of knowledge, that of "opinion", man is under the dominant influence of things outside himself, and so is in the bondage of the passions.

"[17][24][25] Shortly after his death in 1677, Spinoza's works were placed on the Catholic Church's Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

In June 1678—just over a year after Spinoza's death—the States of Holland banned his entire works, since they "contain very many profane, blasphemous and atheistic propositions".

The prohibition included the owning, reading, distribution, copying, and restating of Spinoza's books, and even the reworking of his fundamental ideas.

Locke, Hume, Leibniz and Kant all stand accused by later scholars of indulging in periods of closeted Spinozism.

Spinoza rose clearly into view for Anglophone metaphysicians in the late nineteenth century, during the British craze for Hegel.

In his admiration for Spinoza, Hegel was joined in this period by his countrymen Schelling, Goethe, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.

In the twentieth century, the ghost of Spinoza continued to show itself, for example in the writings of Russell, Wittgenstein, Davidson, and Deleuze.

Among writers of fiction and poetry, the influential thinkers inspired by Spinoza include Coleridge, George Eliot, Melville, Borges, and Malamud.

Some have attempted to resolve this conflict, such as Linda Trompetter, who writes that "attributes are singly essential properties, which together constitute the one essence of a substance",[31] but this interpretation is not universal, and Spinoza did not clarify the issue in his response to de Vries.