Euoplocephalus

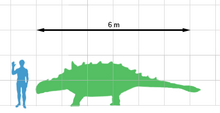

Euoplocephalus (/juːˌɒploʊˈsɛfələs/ yoo-OP-loh-SEF-ə-ləs) is a genus of large herbivorous ankylosaurid dinosaurs, living during the Late Cretaceous of Canada.

The skull of Euoplocephalus can be distinguished from most other ankylosaurids by several anatomical details, including: the pattern of bony sculpturing in the region in front of the eyes; the form of the palpebral bones (small bones over the eyes),[2] which may have served as bony eyelids;[3] the shallowness of the nasal vestibule at the entrance of the nasal cavity;[2] the medial curve of the tooth rows in the upper jaw; and the teeth, which are relatively small, lacking true cingula, and having variable fluting of the denticles.

[5] In 2013, Victoria Arbour and Phil Currie provided a differential diagnosis, setting Euoplocephalus apart from its nearest relatives.

It differs from Scolosaurus in possessing keeled osteoderms with a round or oval base on the top and sides of the first cervical half-ring and having a shorter rear blade of the ilium.

Euoplocephalus differs from Ankylosaurus in possessing anteriorly directed external nostrils and in lacking a continuous keel between the squamosal horn and the supraorbitals.

The strongly drooping snout is blunt, wide and high, and filled with very complex air passages and sinuses, the form and function of which are not yet completely understood.

This is an error based on a restoration of Scolosaurus by Franz Nopcsa; the specimen he used had an incomplete tail that stopped just beyond the pair of conical spikes now known to have been positioned halfway along its length.

[4] The head and body of Euoplocephalus were covered with bony armor, except for parts of the limbs and possibly the distal tail.

This armor was in 1982 extensively described by Kenneth Carpenter, who however, largely based himself on the very complete specimen NHMUK R5161, the holotype of Scolosaurus,[6] which genus no longer is seen as a synonym of Euoplocephalus.

[4] In any case, much of the armor was made up of small ossicles, bony round scutes with a diameter of less than five millimetres, of which often hundreds have been found with a single specimen.

If the armor was configured in an identical way to that of Scolosaurus, many of these small ossicles had fused into a kind of pavement, forming transverse bands on the body.

[6] Four of these bands might have been present on the anterior half of the tail, three on the pelvis, perhaps fused into a single "sacral shield", and four across the front part of the torso.

It might be that the scutes on the shoulder, near the midline of the body, were largest and tallest; ROM 1930 includes some osteoderms with a base length of fifteen centimeters.

Earlier seen as a fusion of osteoderms,[6] this was doubted by Arbour et al. in 2013, who pointed out that they formed a lower layer, possibly consisting of ossified cartilage, as indicated by a smooth surface and a woven bone texture.

At the lower rear side of the skull, a quadratojugal horn is present, in the form of an enormous tongue-shaped osteoderm projecting below.

[4] Canadian paleontologist Lawrence Morris Lambe discovered the first specimen on 18 August 1897 in the area of the present Dinosaur Provincial Park, in the valley of the Red Deer River, Alberta, Canada.

The generic name was derived from Greek στερεός, stereos, "solid", and κεφαλή, kephalè, "head", which refers to the formidable armour.

[15] The fossils now referred to this species contained more than forty individuals discovered in Alberta, Canada and Montana in the United States, which would have made Euoplocephalus the best known ankylosaurid.

A 2009 study found that Dyoplosaurus is in fact a valid taxon, and identified unique characteristics that differentiated it from Euoplocephalus, including its triangular claws.

[21] In 2013 Arbour limited the specimens that could be reliably referred to Euoplocephalus to the lowest thirty metres of the Dinosaur Park Formation.

[22] In 1910, Lambe assigned Euoplocephalus to the Stegosauria, a group then encompassing all armoured dinosaur forms and thus having a much wider range than the present concept.

The recent splitting of the ankylosaurid Campanian material of North America has complicated the issue of the direct affinities of Euoplocephalus.

[19] The following cladogram is based on a 2015 phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosaurinae conducted by Arbour and Currie:[24] Crichtonpelta Tsagantegia Zhejiangosaurus Pinacosaurus Saichania Tarchia Zaraapelta Dyoplosaurus Talarurus Nodocephalosaurus Ankylosaurus Anodontosaurus Euoplocephalus Scolosaurus Ziapelta The results of an earlier analysis of the ankylosaurid tree by Thompson et al. (2011), is shown by this cladogram.

[25] Minmi Liaoningosaurus Cedarpelta Gobisaurus Shamosaurus Tsagantegia Zhongyuansaurus Shanxia Crichtonsaurus Dyoplosaurus Pinacosaurus mephistocephalus Ankylosaurus Euoplocephalus Minotaurasaurus Pinacosaurus Nodocephalosaurus Talarurus Tianzhenosaurus Tarchia Saichania Euoplocephalus, following the synonymizations proposed by Coombs (1971), was thought to exist for far longer, and was a member of more distinct faunas, than any of its contemporaries, as these fossils dated to between 76.5 and 67 million years ago in the Campanian-Maastrichtian ages of the late Cretaceous period, and came from the Dinosaur Park and Horseshoe Canyon Formations of Alberta, Two Medicine Formation of Montana, and possibly from the Oldman Formation of Alberta.

[18] Although the stratigraphic range of the holotype of Euoplocephalus is uncertain, all specimens that can be reliably referred to E. tutus came from the lower 40 m and the upper >10 m of the Dinosaur Park Formation.

[30] A 2009 study concluded that "large ankylosaurian clubs could generate sufficient force to break bone during impacts, while average and small ones could not".

The complex respiratory passages observed in the skull suggest that Euoplocephalus had a good sense of smell, although in 1978 an examination of casts of the endocranium did not show an enlarged olfactory region of the brain.

[32] Teresa Maryanska, who has worked extensively on Mongolian ankylosaurids, suggested that the respiratory passages were primarily used to perform a mammal-like treatment[clarification needed] of inhaled air, based on the presence and arrangement of specialized bones,[9] which are present in Euoplocephalus.

[33] A 2011 study found that the nasal passages of Euoplocephalus were looped and complex; possibly an adaptation for heat and water balance and vocal resonance, and researchers discovered an enlarged and vascularised chamber at the back of the nasal tract, which was considered by the authors to be an adaptation to improve its sense of smell.

[36] A study conducted in 2014 found that the ankylosaurs were capable of eating of tough fibrous plant material, though not to the same degree as their nodosaur relatives or the ceratopsians and hadrosaurs.