Eurasianism

The Eurasianists strongly opposed the territorial fragmentation of the Russian Empire that had occurred due to the Bolshevik Revolution and the following civil war (1917–1923).

Many viewed the Soviet Union as a stepping stone on the path of creating a new national identity that would reflect Russia's geopolitical situation.

Eurasianist support for the Soviet Union began in the 1920s during the Stalinist era, which witnessed the emergence of a distinct socialist nationalism through CPSU's enforcement of "Socialism in one country" policy.

In the aftermath of events like the Crimean War and the 1878 Berlin Treaty, widely decried as a national humiliation in Russia, a new breed of monarchist elites who advocated eastward expansion, known as vostochniki (Orientalizers), emerged.

Many of the vostochniki began emphasizing their "Asianness" to defend the Russian Empire from what they viewed as "intellectual colonization" from the Romano-Germanic cultures of Western Europe.

However, the terminology deployed by the vostochniki had mostly remained ambiguous, with their ideas not attaining a structural ideological character, and served within the frame of Russian imperial interests.

As anti-monarchists and proponents of an authoritarian republic, Eurasianists praised many aspects of the October Revolution, and they portrayed the Bolshevik movement as a necessary reaction to the rapid modernization of Russian society.

These Eurasianists criticized the anti-Bolshevik activities of organizations such as ROVS, believing that the émigré community's energies would be better focused on preparing for this hoped for process of evolution.

These included the American white nationalist and neo-Nazi Francis Parker Yockey,[23] the Belgian Nazi collaborator Jean-François Thiriart and interwar German National Bolsheviks.

Alexander Rutskoy, the vice president of Russia from 1991 to 1993, asserted irredentist claims to Narva in Estonia, Crimea in Ukraine, and Ust-Kamenogorsk in Kazakhstan, among other territories.

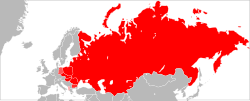

[28] Defunct Drawing on historical, geographical, ethnographical, linguistic, cultural and religious studies, the Eurasianists suggested that the lands of the Russian Empire, and then of the Soviet Union, formed a natural unity.

[29] According to French historian Marlene Laurelle, despite admiring aspects of European fascist movements, early Eurasianist intellectuals were repelled by their glorification of violence, militarism, extremism, racism, etc.

[32]For David Lewis, there are a number of people who assert "an alternative topography, articulated in a series of spatial projects – the 'Russian World', 'Eurasian integration', 'Greater Eurasia' – which aims to carve out a space in opposition to the 'spacelessness' of Western-dominated global order.

Academics such as Natalya Narochnitskaya, Yegor Kholmogorov, and Vadim Tsymburskii all espouse a messianic version of Eurasianism, and twin it with some form of Eastern Orthodox Church theology.

[38][39][40][41][42] The organization follows the neo-Eurasian ideology, which adopts an eclectic mixture of Russian patriotism, Orthodox faith, anti-modernism, and even some Bolshevik ideas.

Researchers note that in the formulation of philosophical problems and political projects, he significantly deviates from classical Eurasianism, which is presented in his numerous works very selectively, eclectically.

[47] Political scientist Anton Shekhovtsov defined Dugin's version of Neo-Eurasianism as "a form of a fascist ideology centred on the idea of revolutionising the Russian society and building a totalitarian, Russia-dominated Eurasian Empire that would challenge and eventually defeat its eternal adversary represented by the United States and its Atlanticist allies, thus bringing about a new 'golden age' of global political and cultural illiberalism".

[48] Australian russologist Paul Dibb identifies Putin, supported by Panarin, Karaganov and Dugin, as having "begun to stress the geopolitics of what they call 'Eurasianism', which is an intellectual movement promoting an ideology of Russian–Asian greatness."

[36] Igor Torbakov argued in June 2022 that "According to the Kremlin's geopolitical outlook, Russia could only successfully compete with the United States, China or the European Union if it acts as a leader of the regional bloc.

Bringing Russia and its ex-Soviet neighbours into a closely integrated community of states, Russian strategists contend, would allow this Eurasian association to become one of the major centres of global and regional governance.

"[52] Ideologically, President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev's speech in March 1994 at Moscow State University became the starting point for the implementation of a pragmatic Eurasianism.

[55] Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia and former Russian President, in 2022, has declared on his Telegram channel the state goal "to finally build Eurasia from Lisbon to Vladivostok.

The document also adopts a neo-Soviet posture, positioning Russia as the successor state of USSR and calls for spreading "accurate information" about the "decisive contribution of the Soviet Union" in shaping the post-WWII international order and the United Nations.

[60] In the future time depicted in George Orwell's novel Nineteen Eighty Four, the Soviet Union has mutated into Eurasia, one of the three superstates dominating the world.