Eureka Flag

[8] The Port Phillip District was partitioned on 1 July 1851 by the Australian Constitutions Act 1850, as Victoria gained autonomy within the British Empire after a decade of de facto independence from New South Wales.

The response was a universal mining tax based on time stayed, rather than what was seen as the more equitable option, being an export duty levied only on gold found, meaning it was always designed to make life unprofitable for most prospectors.

[15] Licence inspections, known as "digger hunts", were treated as a great sport and "carried out in the style of an English fox-hunt"[16] by mounted officials who received a fifty per cent commission from any fines imposed.

[18] Miners were often arrested for not carrying licences on their person because of the typically wet and dirty conditions in the mines, then subjected to such indignities as being chained to trees and logs overnight.

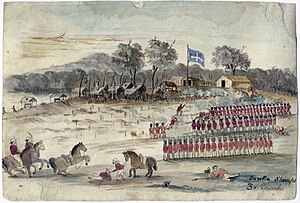

[22] On 28 November, there was a skirmish as the approaching 12th Regiment (East Suffolk) had their wagon train looted in the vicinity of the Eureka lead, where the rebels ultimately made their last stand.

[23] The next day, the Eureka Flag appeared on the platform for the first time, and mining licences were burnt at the final fiery mass meeting of the Ballarat Reform League – the miner's lobby.

The league's founding charter proclaims that "it is the inalienable right of every citizen to have a voice in making the laws he is called upon to obey" and "taxation without representation is tyranny",[24] in the language of the United States Declaration of Independence.

[26] The rebels, under their commander-in-chief Peter Lalor, who had left Ireland for the gold fields of Australia, were led down the road from Bakery Hill to the ill-fated Eureka Stockade.

They briefly wavered, with the 40th Regiment (2nd Somersetshire) having to be rallied amid a short, sharp exchange of ranged fire lasting around 15 minutes at dawn on Sunday, 3 December.

[28][29] The earliest mention of a flag was the report of a meeting held on 23 October 1854 to discuss indemnifying Andrew McIntyre and Thomas Fletcher, who had both been arrested and committed for trial over the burning of the Eureka Hotel.

"[30] In 1885, John Wilson, whom the Victorian Works Department employed at Ballarat as a foreman, claimed that he had originally conceptualised the Eureka Flag after becoming sympathetic to the rebel cause.

In a letter to the editor published in the Melbourne Age, 15 January 1855 edition, Fredrick Vern states that he "fought for freedom's cause, under a banner made and wrought by English ladies".

[53] Norm D'Angri theorises that the Eureka Flag was hastily manufactured, and the number of points on the stars is a mere convenience as eight was "the easiest to construct without using normal drawing instruments".

"[60] In a despatch dated 20 December 1854, Lieutenant-Governor Charles Hotham said: "The disaffected miners ... held a meeting whereat the Australian flag of independence was solemnly consecrated and vows offered for its defence.

There is no flag in Europe, or in the civilised world, half so beautiful and Bakery Hill as being the first place where the Australian ensign was first hoisted, will be recorded in the deathless and indelible pages of history.

"[63] Reed called for the formation of a committee of citizens to "beautify the spot, and to preserve the tree stump" upon which Lalor addressed the assembled rebels during the oath swearing ceremony.

"[67] In his report dated 14 December 1854, Captain John Thomas mentioned "the fact of the Flag belonging to the Insurgents (which had been nailed to the flagstaff) being captured by Constable King of the Force".

[73][21] The morning after the battle, "the policeman who captured the flag exhibited it to the curious and allowed such as so desired to tear off small portions of its ragged end to preserve as souvenirs.

[75] Furthermore, concerning the "overt acts" that constituted the actus reus of the offence, the indictment read: "That you raised upon a pole, and collected round a certain standard, and did solemnly swear to defend each other, with the intention of levying war against our said Lady the Queen".

[84] In Labour History, Professor Beggs-Sunter states that the art gallery displayed the flag "in various unsuitable ways" until it was put in a glass case alongside the sword of Captain Wise in October 1934, which she described as an "unlikely juxtaposition".

When peace activist Egon Kisch visited the gallery the following year, he wrote that the Eureka monument "heroes and minions of the law, fighters and executioners ... on the same level".

After being told about it by his friend Rem McClintock in December 1944, Sydney journalist Len Fox, who worked with the Communist Party media, published an article about the flag during his investigation that followed on from Withers'.

Two sketches, in particular, show the design is the same as the tattered remains of the original flag that were first put on public display at the art gallery in 1973, being unveiled during a ceremony attended by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

[116][117] Construction union boss Kevin Reynolds and the Northern Territory's nomination for Australian of the Year, Warwick Thornton, both raised fears in 2010 that the Eureka Flag could "become a swastika-like symbol of racism."

"[117][note 5] In response to the use of the Eureka Flag at violent protests in recent times, efforts have been made by some, including federal Labor MP Catherine King, to reclaim it for more progressive causes.

The marchers were singing "It's a Great Day for the Irish" and "Advance, Australia Fair" whilst carrying shamrock-shaped anti-government placards and a coffin with the label "Trade Unionism.

He was opposed to flying it at Parliament House, Canberra to mark the occasion, stating: "I think people have tried to make too much of the Eureka Stockade ... trying to give it a credibility and standing that it probably doesn't enjoy.

[153] The Australian Labor Party indicated support for the move, with opposition leader Mark Latham saying he was: "pledged to fly it [the Eureka Flag] above [Parliament House] Canberra if he became Prime Minister.

A century after it was first hoisted, however, Australian authors began to recognise that it had been an inspiration, both in spirit and design, for many banners up to and including the current official civil and state flags of the nation.

[162] However, Hugh King, who was a private in the 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot, swore in a signed contemporaneous affidavit that he recalled: ... three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me.