Cinema of Europe

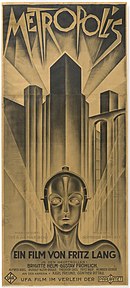

Notable European early film movements include German expressionism (1920s), Soviet montage (1920s), French impressionist cinema (1920s), and Italian neorealism (1940s); it was a period now seen in retrospect as "The Other Hollywood".

Its objective is to provide operational and financial support to cinemas that commit themselves to screen a significant number of European non-national films, to offer events and initiatives as well as promotional activities targeted at young audiences.

The proof of this claim that between 1895 – 1905 France invented the concept of cinema when the Lumière brothers first film screened on 28 December 1895, called The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station, in Paris.

[21] During this period, the French film industry faced a crisis as the number of its produced features decreased and they were surpassed by their competitors including the United States of America and Germany.

[24] In addition, the screening of French literary classics involved La Charterhouse and Rouge et le Noir attained spread great fame across the globe.

One of the main stimulations behind the French impressionist avant-garde was to discover the impression of "pure cinema" and to style film into an art form, and as an approach of symbolism and demonstration rather than merely telling a story.

[32] In the early 1900s, artistic and epic films such as Otello (1906), The Last Days of Pompeii (1908), L'Inferno (1911), Quo Vadis (1913), and Cabiria (1914), were made as adaptations of books or stage plays.

[42] Its cultural importance was considerable and influenced all subsequent avant-gardes, as well as some authors of narrative cinema; its echo expands to the dreamlike visions of some films by Alfred Hitchcock.

Its key figures were the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo.

Most of the futuristic-themed films of this period have been lost, but critics cite Thaïs (1917) by Anton Giulio Bragaglia as one of the most influential, serving as the main inspiration for German Expressionist cinema in the following decade.

Giuseppe De Santis, on other hand, used actors such as Silvana Mangano and Vittorio Gassman in his 1949 film, Bitter Rice, which is set in the Po Valley during rice-harvesting season.

Poetry and cruelty of life were harmonically combined in the works that Vittorio De Sica wrote and directed together with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini: among them, Shoeshine (1946), The Bicycle Thief (1948) and Miracle in Milan (1951).

It is widely considered to have started with Mario Monicelli's Big Deal on Madonna Street in 1958[60] and derives its name from the title of Pietro Germi's Divorce Italian Style, 1961.

[62][63][64] Rather than a specific genre, the term indicates a period (approximately from the late 1950s to the early 1970s) in which the Italian film industry was producing many successful comedies, with some common traits like satire of manners, farcical and grotesque overtones, a strong focus on "spicy" social issues of the period (like sexual matters, divorce, contraception, marriage of the clergy, the economic rise of the country and its various consequences, the traditional religious influence of the Catholic Church) and a prevailing middle-class setting, often characterized by a substantial background of sadness and social criticism that diluted the comic contents.

[65] The success of films belonging to the "Commedia all'italiana" genre is due both to the presence of an entire generation of great actors, who knew how to masterfully embody the vices and virtues, and the attempts at emancipation but also the vulgarities of the Italians of the time, both to the careful work of directors, storytellers and screenwriters, who invented a real genre, with essentially new connotations, managing to find precious material for their cinematographic creations in the folds of a rapid evolution with many contradictions.

Monicelli's works include La grande guerra (The Great War), I compagni (The Organizer), L'armata Brancaleone, Vogliamo i colonnelli (We Want the Colonels), Romanzo popolare (Come Home and Meet My Wife) and the Amici miei (My Friends) series.

Another popular Spaghetti Western film is Sergio Corbucci Django (1966), starring Franco Nero as the titular character, another Yojimbo plagiarism, produced to capitalize on the success of A Fistful of Dollars.

[81] Giallo films are generally characterized as gruesome murder-mystery thrillers that combine the suspense elements of detective fiction with scenes of shocking horror, featuring excessive bloodletting, stylish camerawork and often jarring musical arrangements.

The structure of giallo films is also sometimes reminiscent of the so-called "weird menace" pulp magazine horror mystery genre alongside Edgar Allan Poe and Agatha Christie.

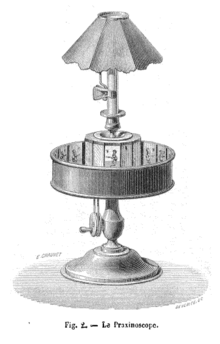

One of the key figures in the early history of film was Ottmar Anschütz (1866–1907), a German photographer and inventor who, alongside the Lumière brothers and Thomas Edison, played a role in the development of the motion picture camera and projector.

The moody lighting and stark contrasts of early Hollywood thrillers, such as The Cat and the Canary (1927) and The Invisible Man (1933), owe a great debt to the cinematic innovations pioneered in Germany.

Likewise, the film noir genre, which emerged in the 1940s, drew heavily from the visual language of German Expressionism, incorporating its chiaroscuro lighting, distorted angles, and themes of paranoia and alienation.

Films such as Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast (1946) and Orson Welles’ The Trial (1962) would echo the surreal, fragmented style of Expressionist cinema, demonstrating the enduring legacy of the movement.

Riefenstahl's stunning cinematography and groundbreaking use of camera angles, lighting, and editing made the event seem grand and inevitable, framing Hitler as a charismatic leader surrounded by a devoted, heroic populace.

DEFA's output was heavily influenced by socialist realism, the artistic doctrine that promoted themes of class struggle, collective unity, and the triumph of socialism over capitalism.

Over the decades, East German cinema evolved, adapting to changing political circumstances and growing tensions between the state’s strict control and the filmmakers' desire for creative expression.

Directors like Helmut Käutner and Wolfgang Staudte attempted to deal with the trauma of the Nazi past, but films often focused more on escapism and rebuilding national identity.

The New German Cinema was characterized by its intellectual rigor, experimental storytelling, and a willingness to confront difficult subjects, including Germany's Nazi past, the aftermath of war, and the country’s fractured identity.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent reunification of Germany in 1990 marked a profound moment in the country’s history, and this political upheaval had a direct impact on German cinema.

Filmmakers from both East and West Germany began to engage with the legacies of division and reunification, exploring how the historical and political fragmentation of the country affected individual and collective identities.