History of the Jews in Europe

A notable early event in the history of the Jews in the Roman Empire was the 63 BCE siege of Jerusalem, where Pompey had interfered in the Hasmonean civil war.

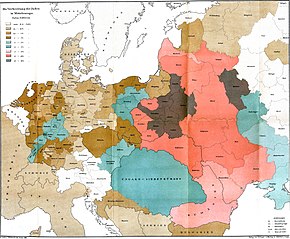

Jews have had a significant presence in European cities and countries since the fall of the Roman Empire, including Italy, Spain, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, and Russia.

Emancipation often brought more opportunities for Jews and many integrated into larger European society and became more secular rather than remaining in cohesive Jewish communities.

Large numbers of Jews lived in Greece (including the Greek isles in the Aegean and Crete) as early as the beginning of the 3rd century BCE.

[12] In the wake of Alexander the Great's conquests, Jews migrated from the Middle East to Greek settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean, spurred on by the opportunities they expected.

[13] As early as the middle of the 2nd century BCE, the Jewish author of the third book of the Oracula Sibyllina, addressing the "chosen people", says: "Every land is full of thee and every sea."

The most diverse witnesses, such as Strabo, Philo, Seneca, Cicero, and Josephus, all mention Jewish populations in the cities of the Mediterranean Basin.

[14] At the commencement of the reign of Caesar Augustus in 27 BCE, there were over 7,000 Jews in Rome: this is the number that escorted the envoys who came to demand the deposition of Archelaus.

When the Roman Empire captured Jerusalem in 63 BCE, thousands of Jewish prisoners of war were brought from Judea to Rome, where they were sold into slavery.

[16] After the enslaved Jews gained their freedom, they permanently settled in Rome on the right bank of the Tiber as traders, and some immigrated north later.

A finger ring with a menorah depiction found in Augusta Raurica (Kaiseraugst, Switzerland) in 2001 attests to Jewish presence in Germania Superior.

[33][34][35][36] This Jewish migration was motivated by economic opportunities and often at the invitation of local Christian rulers, who perceived the Jews as having the know-how and capacity to jump-start the economy, improve revenue, and enlarge trade.

In relations with Christian society, they were protected by kings, princes and bishops, because of the crucial services they provided in three areas: finance, administration, and medicine.

As a result of persecution, expulsions and massacres carried out by the Crusaders, Jews gradually migrated to Central and Eastern Europe, settling in Poland, Lithuania, and Russia, where they found greater security and a renewal of prosperity.

The Early Modern period was one of considerable transition in European Jewry, with forced expulsions and religious persecution in many Christian kingdoms, but there were significant political and cultural changes that saw more favorable conditions for Jewish populations.

One in particular, the Protestant Dutch Republic was founded with religious tolerance as a core value, such that Jews could practice their religion openly and generally without restriction and there were opportunities for Jewish merchants to compete on an equal basis in a burgeoning world economy.

Pejorative tropes of Jews in the medieval period did not entirely disappear, but there were now straightforward scenes of Jewish religious worship and everyday life, indicating more tolerant attitudes by larger Western European society.

There had already been considerable pressure for Jews to convert to Christianity and to monitor that their conversions were sincere and orthodox, the Holy Office of the Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 by Ferdinand and Isabella to maintain Catholic orthodoxy.

When the Protestant Dutch Republic revolted against Catholic Spain in what became the Eighty Years' War, Portuguese and Spanish Jews forced to convert to Catholicism (conversos or Marranos) began migrating to the northern provinces of the Netherlands.

2,000) in 1290, but in the seventeenth century, prominent Portuguese Jewish rabbi Menasseh ben Israel petition Oliver Cromwell to permit Jews to live and work in England.

His son, Sigismund II Augustus (r. 1548–1572), mainly followed the tolerant policy of his father and also granted autonomy to the Jews in the matter of communal administration, laying the foundation for the power of the Qahal, or autonomous Jewish community.

[58][59][60] In the middle of the 16th century, Poland welcomed Jewish newcomers from Italy and Turkey, mostly of Sephardi origin; while some of the immigrants from the Ottoman Empire claimed to be Mizrahim.

Polish Jewry found its views of life shaped by the spirit of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, whose influence was felt in the home, in school, and in the synagogue.

In the first half of the 16th century the seeds of Talmudic learning had been transplanted to Poland from Bohemia, particularly from the school of Jacob Pollak, the creator of Pilpul ("sharp reasoning").

His contemporary and correspondent Solomon Luria (1510–1573) of Lublin also enjoyed widespread popularity among his co-religionists; and the authority of both was recognized by the Jews throughout Europe.

At the same time, many miracle workers made their appearance among the Jews of Poland, culminating in a series of false "Messianic" movements, most famously Sabbateanism and Frankism.

Into this time of mysticism and overly formal rabbinism came the teachings of Israel ben Eliezer, known as the Baal Shem Tov, or BeShT, (1698–1760), which had a profound effect on the Jews of Central Europe and Poland in particular.

As the Czarist monarchy was openly antisemitic;[66][67] various pogroms, which were large-scale violent protests directed at Jews, took place across the western part of the vast empire since late 19th century,[68] leading to several deaths and waves of emigration.

[citation needed] Starting in the 19th century after Jewish emancipation, European Jews left the continent in huge numbers, especially for the United States and some other countries, to pursue better opportunity and to escape religious persecution, including pogroms, and to flee violence.

Although the non-Jewish Germans then began to come in lower numbers, Jewish immigration continued to be robust into the twentieth century, an estimated 250,000.