European enslavement of Indigenous Americans

[5] After the decolonization of the Americas, the enslavement of Indigenous peoples continued into the 19th century in frontier regions of some countries, notably parts of Brazil, Peru[6] Northern Mexico, and the Southwestern United States.

In Christopher Columbus's letter to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain describing the native Taíno, he remarks that "They ought to make good and skilled servants"[8] and "these people are very simple in war-like matters...

The new international market for products like tobacco, sugar, and raw materials incentivized the creation of extraction- and plantation-based economies in eastern North America, such as English Carolina, Spanish Florida, and (Lower) French Louisiana.

[12][4][1][2] Anthropologist David Graeber argued that debt and the threat of violence made this sort of transformation of human beings into commodities possible.

[citation needed] The export of slaves to European colonies (and the high death rates there) created an unprecedented population drain.

[b][14][1][2][15] By the mid eighteenth century, population decline, frequent rebellions, and the availability of African slaves had caused a shift away from the large-scale enslavement of Indigenous peoples.

[16] This created a demand for large amounts of cheap labor, and an estimated 400,000 Taíno people from across the island were soon enslaved to work in gold mines.

[21] Although based on similar grants given during the Reconquista in Spain, in the Caribbean the system quickly became indistinguishable from the slavery it replaced[5] By 1508, the original Taíno population of 400,000 or more had been reduced to around 60,000.

[23] Historian Andrés Reséndez at the University of California, Davis asserts that even though disease was a factor, the Indigenous population of Hispaniola would have rebounded the same way Europeans did following the Black Death if it were not for the constant enslavement they were subject to.

Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, author of A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, publicized the conditions of Indigenous Americans and lobbied Charles V to guarantee their rights.

[29] The implementation of the New Laws and liberation of tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans led to a number of rebellions and conspiracies by encomenderos which were put down by the Spanish crown.

"Spanish masters resorted to slight changes in terminology, gray areas, and subtle reinterpretations to continue to hold Indians in bondage.

When the market for slaves began to dry up in the early 18th century, the surplus and ex-slaves settled in New Mexico, forming communities of so-called Genízaros.

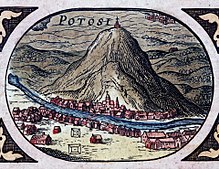

[46] This only increased the burden on the remaining natives, and by the 1600s, up to half of the eligible male population (as opposed to the repartimiento's original 7–10%) might find themselves working at Potosí in any given year.

[61] While the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal allowed the enslavement of First Nations people to continue, by the late 18th century it had largely been eclipsed by the Atlantic slave trade.

[e][66][67][f] The enslavement and trafficking of Indigenous American people was also practiced in the Province of Carolina, where historian Alan Gallay notes that during this period more slaves were exported from than imported to the major port of Charles Town.

Traded goods, such as axes, bronze kettles, Caribbean rum, European jewelry, needles, and scissors, varied among the tribes, but the most prized were rifles.

[71] The depletion of Indigenous populations coupled with revolts (such as the Yamasee War) would eventually lead to Native Americans being replaced with African slaves in the colonial southeast.

In 1661, for example, Padre António Vieira's attempts to protect native populations lead to an uprising and the temporary expulsion of the Jesuits in Maranhão and Pará.

While travelling along the Japura River in 1827, English lieutenant Henry Lister Maw noted that slave raids for men, women and children in the Putumayo and Japurá region had been going on for over one hundred years.

"[84][85] Due to the nature of California court records, it is difficult to estimate of the number of Native Americans enslaved as a result of the legislation.

[93] This move was not without opposition: soon after the treaty had been signed, a group of prominent New Mexicans petitioned Congress to prevent slavery from being made legal.

[97][98] Taking advantage of their vulnerable position, Mexican and Ute enslavers captured many Navajo and sold them as slaves in places as far away as Conejos County, Colorado.

[4] Shortly after the Mormon pioneers settled Salt Lake City on the lands of the Western Shoshone, Weber Ute,[103] and Southern Paiute,[104] conflict with nearby Native American groups began.

[105][page needed] In the winter of 1849–1850, after expanding into Parowan, Mormons attacked a group of Indians, killing around 25 men and taking the women and children as slaves.

[109][110] In 1851, Apostle George A. Smith gave Chief Peteetneet and Walkara talking papers that certified "it is my desire that they should be treated as friends, and as they wish to Trade horses, Buckskins and Piede children, we hope them success and prosperity and good bargains.

When Don Pedro León Luján was caught violating the Nonintercourse Act in November 1851 by attempting to trade slaves with the Indians without a valid license, he and his party were prosecuted.

Bent's Fort, a trading post on the Santa Fe Trail, was one customer of the enslavers, as were Comancheros, Hispanic traders based in New Mexico.

In what would become the southwestern United States, the Comanche, Chiricahua, and Ute peoples played a similar role capturing and selling slaves, first to Mexican and then American settlers.

[123] The fact that the Cherokee nation held African slaves played a role in their decision to side with the Confederacy in the American Civil War.