European wars of religion

[3][10][11][12] In 1517, Martin Luther's Ninety-five Theses took only two months to spread throughout Europe with the help of the printing press, overwhelming the abilities of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the papacy to contain it.

He concluded that while many Puritans took up arms in protest against the religious reforms promoted by Charles I of England, they often justified their opposition as a revolt against a monarch who had violated crucial constitutional principles, and thus had to be overthrown.

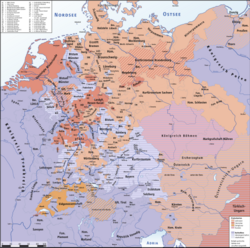

"[17] Individual conflicts that may be distinguished within this topic include: The Holy Roman Empire, encompassing present-day Germany and surrounding territory, was the area most devastated by the wars of religion.

The Austrian House of Habsburg, who remained Catholic, was a major European power in its own right, ruling over some eight million subjects in present-day Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Hungary.

A vast number of minor independent duchies, free imperial cities, abbeys, bishoprics, and small lordships of sovereign families rounded out the Empire.

In Northern Germany, Luther adopted the tactic of gaining the support of the local princes and city elites in his struggle to take over and re-establish the church along Lutheran lines.

The Elector of Saxony, the Landgrave of Hesse, and other North German princes not only protected Luther from retaliation from the edict of outlawry issued by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, but also used state power to enforce the establishment of Lutheran worship in their lands, in what is called the Magisterial Reformation.

Martin Luther rejected the demands of the insurgents and upheld the right of Germany's rulers to suppress the uprisings,[33] setting out his views in his polemic Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants.

In 1532 the Emperor, pressed by external troubles, stepped back from confrontation, offering the "Peace of Nuremberg", which suspended all action against the Protestant states pending a General Council of the Church.

The conflict ended with the advantage of the Catholics, and the Emperor was able to impose the Augsburg Interim, a compromise allowing slightly modified worship, and supposed to remain in force until the conclusion of a General Council of the Church.

[21] The Peace of Augsburg (1555), signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, confirmed the result of the 1526 Diet of Speyer and ended the violence between the Lutherans and the Catholics in Germany.

Religious tensions also broke into violence in the German free city of Donauwörth in 1606, when the Lutheran majority barred the Catholic residents from holding a procession, provoking a riot.

Beginning as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire, it gradually developed into a general war involving much of Europe, for reasons not necessarily related to religion.

Episodes of widespread famine and disease devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries and Italy, while bankrupting many of the powers involved.

Under the leadership of the exiled William the Silent, the Catholic and Protestant-dominated provinces sought to establish religious peace while jointly opposing the king's regime with the Pacification of Ghent, but the general rebellion failed to sustain itself.

Despite Governor of Spanish Netherlands and General for Spain, the Duke of Parma's steady military and diplomatic successes, the Union of Utrecht continued their resistance, proclaiming their independence through the 1581 Act of Abjuration and establishing the Calvinist-dominated Dutch Republic in 1588.

In a pattern soon to become familiar in the Netherlands and Scotland, underground Calvinist preaching and the formation of covert alliances with members of the nobility quickly led to more direct action to gain political and religious control.

In February 1563, at Orléans, Francis, Duke of Guise was assassinated, and Catherine's fears that the war might drag on led her to mediate a truce and the Edict of Amboise (1563), which again provided for a controlled religious toleration of Protestant worship.

Coligny and his troops retreated to the south-west and regrouped with Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, and in the spring of 1570, they pillaged Toulouse, cut a path through the south of France and went up the Rhone valley to La Charité-sur-Loire.

The period of the French Wars of Religion effectively removed France's influence as a major European power, allowing the Catholic forces in the Holy Roman Empire to regroup and recover.

In 1625, as part of the Thirty Years' War, Christian IV, who was also the Duke of Holstein, agreed to help the Lutheran rulers of neighbouring Lower Saxony against the forces of the Holy Roman Empire by intervening militarily.

The reformation continued to be imposed on an often unwilling population with the aid of stern laws[45] that made it treason, punishable by death, to oppose the King's actions with respect to religion.

[46] The next major armed resistance took place in the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, which was an unsuccessful rising in western England against the enforced substitution of Cranmer's English language service for the Latin Catholic Mass.

England, Scotland and Ireland, in personal union under the Stuart king, James I & VI, continued Elizabeth I's policy of providing military support to European Protestants in the Netherlands and France.

In an attempt to gain an advantage in numbers, Charles negotiated a ceasefire with the Catholic rebels in Ireland, freeing up English troops to fight on the Royalist side in England.

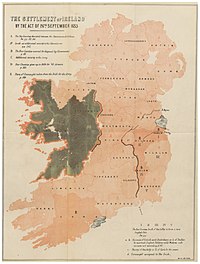

The joint Royalist and Confederate forces under the Duke of Ormonde attempted to eliminate the Parliamentary army holding Dublin, but their opponents routed them at the Battle of Rathmines (2 August 1649).

As the former Member of Parliament Admiral Robert Blake blockaded Prince Rupert's fleet in Kinsale, Oliver Cromwell could land at Dublin on 15 August 1649 with an army to quell the Royalist alliance in Ireland.

The siege of Drogheda and massacre of nearly 3,500 people[citation needed]—comprising around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and all the men in the town carrying arms, including civilians, prisoners, and Catholic priests—became one of the historical memories that has driven Irish-English and Catholic-Protestant strife during the last three centuries.

The victors confiscated almost all Irish Catholic-owned land in the wake of the conquest and distributed it to the Parliament's creditors, to the Parliamentary soldiers who served in Ireland, and to English people who had settled there before the war.

During the subsequent Jacobite rising of 1689, instigated by James' Roman Catholic and Anglican Tory supporters,[2] the Calvinist forces in the south and lowlands of Scotland triumphed.