Eurovision Song Contest

Thousands of spectators attend each year, along with journalists who cover all aspects of the contest, including rehearsals in venue, press conferences with the competing acts, in addition to other related events and performances in the host city.

While having gained popularity with the viewing public in both participating and non-participating countries, the contest has also been the subject of criticism for its artistic quality as well as a perceived political aspect to the event.

[4][5][6] The EBU's general assembly agreed to the organising of the song contest in October 1955, under the initial title of the European Grand Prix, and accepted a proposal by the Swiss delegation to host the event in Lugano in the spring of 1956.

[44][45] Viewers are welcomed by one or more presenters who provide key updates during the show, conduct interviews with competing acts from the green room, and guide the voting procedure in English and French.

[59] However, there is a perception reflected in popular culture that some countries wish to avoid the costly burden of hosting – sometimes resulting in them sending deliberately subpar entries with no chance of winning.

[77] Preparations in the host venue typically begin approximately six weeks before the final, to accommodate building works and technical rehearsals before the arrival of the competing artists.

[86] A welcome reception is typically held at a venue in the host city on the Sunday preceding the live shows, which includes a red carpet ceremony for all the participating countries and is usually broadcast online.

These rules have changed over time, and typically outline, among other points, the eligibility of the competing songs, the format of the contest, and the voting system to be used to determine the winner and how the results will be presented.

[48] Previously live backing vocals were also required; since 2021 these may optionally be pre-recorded – this change has been implemented in an effort to introduce flexibility following the cancellation of the 2020 edition and to facilitate modernisation.

This was changed from a random draw used in previous years in order to provide a better experience for television viewers and ensure all countries stand out by avoiding instances where songs of a similar style or tempo are performed in sequence.

[100][112] With advances in telecommunication technology, televoting was first introduced to the contest in 1997 on a trial basis, with broadcasters in five countries allowing the viewing public to determine their votes for the first time.

[138] Historically, the announcements were made through telephone lines from the countries of origin, with satellite links employed for the first time in 1994, allowing the spokespersons to be seen visually by the audience and TV spectators.

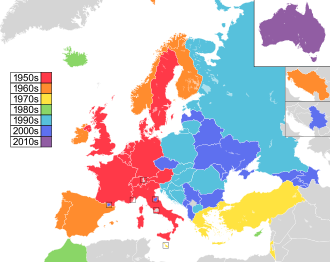

[99][158] Besides slight modifications to the voting system and other contest rules, no fundamental changes to the contest's format were introduced until the early 1990s, when events in Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to the breakup of Yugoslavia, with the subsequent admission into the EBU of the broadcasters of the countries that emerged from the breakup, and to the merger in 1993 of the EBU with its Eastern European counterpart, the International Radio and Television Organisation (OIRT), which further expanded the number of broadcasters by including those from countries of the former Eastern Bloc.

A pre-selection method was subsequently introduced for the first time in order to reduce the number of competing entries, with seven countries in Central and Eastern Europe participating in Kvalifikacija za Millstreet, held in Ljubljana, Slovenia one month before the event.

[140][184] Julio Iglesias was relatively unknown when he represented Spain in 1970 and placed fourth, but worldwide success followed his Eurovision appearance, with an estimated 100 million records sold during his career.

[185][186] Australian-British singer Olivia Newton-John represented the United Kingdom in 1974, placing fourth behind ABBA, but went on to sell an estimated 100 million records, win four Grammy Awards, and star in the critically and commercially successful musical film Grease.

[210] Many well-known composers and lyricists have penned entries of varying success over the years, including Serge Gainsbourg,[211][212] Goran Bregović,[213] Diane Warren,[214] Andrew Lloyd Webber,[215][216] Pete Waterman,[217][218] and Tony Iommi,[219] as well as producers Timbaland[220] and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo.

The Netherlands' Annie M. G. Schmidt, lyricist of the first entry performed at Eurovision, has gained a worldwide reputation for her stories and earned the Hans Christian Andersen Award for children's literature.

[223][224][225] Figures who carved a career in politics and gained international acclaim for humanitarian achievements include contest winner Dana as a two-time Irish presidential candidate and Member of the European Parliament (MEP);[226][227] Nana Mouskouri as Greek MEP and a UNICEF international goodwill ambassador;[228][229] contest winner Ruslana as member of Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine's parliament and a figure of the Orange Revolution and Euromaidan protests, who gained global honours for leadership and courage;[230][231][232] and North Macedonia's Esma Redžepova as member of political parties and a two-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee.

[246][247][248] The 2021 contest saw the next major breakthrough success from Eurovision, with Måneskin, that year's winners for Italy with "Zitti e buoni", attracting worldwide attention across their repertoire immediately following their victory.

The new record set by Justyna Steczkowska concerns only one country, namely Poland[266][267] Alongside the song contest and appearances from local and international personalities, performances from non-competing artists and musicians have been included since the first edition,[45][268] and have become a staple of the live show.

[272][273] Among other artists who have performed in a non-competitive manner are Danish Europop group Aqua in 2001,[274][275] Finnish cello metal band Apocalyptica in 2007,[276] Russian pop duo t.A.T.u.

The 1999 contest in Israel closed with all competing acts performing a rendition of Israel's 1979 winning song "Hallelujah" as a tribute to the victims of the war in the Balkans,[105][286] a dance performance entitled "The Grey People" in 2016's first semi-final was devoted to the European migrant crisis,[287][288][289] the 2022 contest featured known anti-war songs "Fragile", "People Have the Power" and "Give Peace a Chance" in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine that same year,[290][291] and an interval act in 2023's first semi-final alluded to the refugee crisis caused by the aforementioned invasion.

[296][297] Other traits in past competing entries which have regularly been mocked by media and viewers include an abundance of key changes and lyrics about love and/or peace, as well as the pronunciation of English by non-native users of the language.

[302] Although many of the competing acts each year will fall into some of the categories above, the contest has seen a diverse range of musical styles in its history, including rock, heavy metal, jazz, country, electronic, R&B, hip hop and avant-garde.

Complaints were levied against Ukraine's winning song in 2016, "1944", whose lyrics referenced the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, but which the Russian delegation claimed had a greater political meaning in light of Russia's annexation of Crimea.

[317][318][319] Georgia's planned entry for the 2009 contest in Moscow, Russia, "We Don't Wanna Put In", caused controversy as the lyrics appeared to criticise Vladimir Putin, in a move seen as opposition to the then-Russian prime minister in the aftermath of the Russo-Georgian War.

[397][398][399] Several community events have been held virtually, particularly since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe in 2020, among these EurovisionAgain, an initiative where fans watched and discussed past contests in sync on YouTube and other social media platforms.

[402] In addition, participating broadcasters have occasionally commissioned special Eurovision programmes for their home audiences, and a number of other imitator contests have been developed outside of the EBU framework, on both a national and international level.

[409][410] Following the cancellation of the 2020 contest, the EBU organised a special non-competitive broadcast, Eurovision: Europe Shine a Light, which provided a showcase for the songs that would have taken part in the competition.

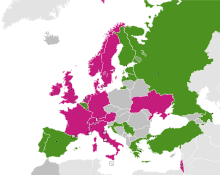

A single hosting Multiple hostings