Evelyn Nesbit

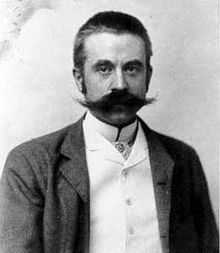

[13] Nesbit's mother finally used letters of introduction given by Philadelphia artists, contacting painter James Carroll Beckwith, whose primary patron was John Jacob Astor.

He took a protective interest in the young Nesbit and provided her with letters of introduction to other legitimate artists, such as Frederick S. Church, Herbert Morgan and Carle J. Blenner.

[15] Elsewhere, Nesbit was featured on the covers of numerous women's magazines, including Vanity Fair, Harper's Bazaar, The Delineator, Ladies' Home Journal and Cosmopolitan.

[16] She appeared in fashion advertising for a wide variety of products; and was also showcased on sheet music and souvenir items – beer trays, tobacco cards, pocket mirrors, postcards, and chromolithographs.

[16] Over time Nesbit became disaffected with the long hours spent in confined environments, maintaining the immobile poses required of a studio model.

An interview was arranged for the aspiring performer with John C. Fisher, company manager of the wildly popular play Florodora, then enjoying a long run at the Casino Theatre on Broadway.

In July 1901, costumed as a "Spanish maiden", Nesbit became a member of the show's chorus line, whose enthusiastic public dubbed them the "Florodora Girls".

He offered her a contract for a year and, more significantly, moved her out of the chorus line and into a position as a featured player – the part of the Gypsy girl "Vashti".

On May 4, 1902, the New York Herald showcased Nesbit in a two-page article, enhanced by photographs, promoting her rise as a new theatrical light and recounting her career from model to chorus line to key cast member.

[21] As a chorus girl on Broadway in 1901, at the age of 15 or 16, Nesbit was introduced to Stanford White, a prominent New York architect, by Edna Goodrich,[22] who was also a member of the company of Florodora.

[26] He soon won over Mrs. Nesbit; in addition to providing the apartment, he paid for Howard to attend the Chester County Military Academy (now Widener University) near Philadelphia.

[29] White worked to separate the couple by arranging for Nesbit's enrollment at a boarding school in New Jersey, administered by Mathilda DeMille, mother of film director Cecil B.

With a history of pronounced mental instability dating to his childhood, Thaw, heir to a $40 million fortune, led a reckless, self-indulgent life.

[41] Nesbit knew her connection with White had already compromised her reputation; if the full extent of their involvement became common knowledge, no respectable man would make her his wife.

As a teenager, she had spent her formative years thrust into the adult society of artists and theatre people; her development had proceeded without the companionship of contemporaries of her own age.

Late that day, Thaw said that he had obtained tickets for the premiere of Mam'zelle Champagne, written by Edgar Allan Woolf, at the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden.

During the finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw produced a pistol and, from two feet away, fired three shots into White's head and back, killing him instantly.

One week after the killing, the film Rooftop Murder was released for public viewing at the nickelodeon theaters, rushed into production by Thomas Edison.

[54] The hard-boiled male reporters of the yellow press were bolstered by a contingent of female counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters"[55] or "The Pity Patrol".

When the case came to trial, the judge banned women from the courtroom – excepting Thaw family members and the female news reporters there on "legitimate business".

In an article titled "The Vivisection of a Woman's Soul", Greeley-Smith described Nesbit's unmaidenly revelations as she testified on the stand: "Before her audience of many hundred men, young Mrs. Thaw was compelled to reveal in all its hideousness every detail of her association with Stanford White after his crime against her.

"[58] The rampant interest in the murder and those involved were used by both the defense and prosecution to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum.

She also knew she was sacrificing her child's soul for money ...."[59] Church groups lobbied to restrict the media coverage, asking the government to step in as censor.

He conferred with the U.S. Postmaster General on the viability of prohibiting the dissemination of such printed matter through the United States mail, and censorship was threatened but never carried out.

"[61] Richard Harding Davis, a war correspondent and reputedly the model for the "Gibson Man", was angered by the yellow press, saying they had distorted the facts about his friend.

Acutely conscious that her own family had a history of hereditary insanity, and after years of protecting her son's hidden life, Mrs. Thaw feared his past would be dragged out into the open, ripe for public scrutiny.

[62] Again maneuvering her way through the gauntlet of reporters, the curious public, the sketch artists and photographers enlisted to capture the effect the "harrowing circumstances [had] on her beauty",[63] Nesbit returned to her hotel and the assembled Thaw family.

To spite them, she then donated the money to anarchist Emma Goldman, who subsequently turned it over to investigative journalist and political activist John Reed.

[78] Despite what one reviewer called an "indifferent vaudeville exhibition", in November 1913, they packed the house at Chicago's Auditorium Theater, drawing an overall audience of 7,400 at the venue, turning away hundreds.

[86] On New Year's Eve 1925, after concluding a six-week engagement at Chicago's Moulin Rouge and before a scheduled appearance in Miami, Nesbit went on a bender and attempted suicide by swallowing disinfectant.