History of life

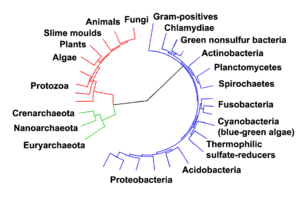

Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as Ga, for gigaannum) and evidence suggests that life emerged prior to 3.7 Ga.[1][2][3] The similarities among all known present-day species indicate that they have diverged through the process of evolution from a common ancestor.

[4] The earliest clear evidence of life comes from biogenic carbon signatures[2][3] and stromatolite fossils[5] discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks from western Greenland.

While eukaryotes may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when aerobic cellular respiration by the endosymbiont mitochondria provided a more abundant source of biological energy.

[18] While microorganisms formed the earliest terrestrial ecosystems at least 2.7 Ga, the evolution of plants from freshwater green algae dates back to about 1 billion years ago.

Many scientists think that about 40 million years after the formation of Earth, it collided with a body the size of Mars, throwing crust material into the orbit that formed the Moon.

[51] This event may well have stripped away any previous atmosphere and oceans; in this case gases and water from comet impacts may have contributed to their replacement, although outgassing from volcanoes on Earth would have supplied at least half.

[53] The earliest identified organisms were minute and relatively featureless, and their fossils looked like small rods that are very difficult to tell apart from structures that arise through abiotic physical processes.

Other good solvents, such as ammonia, are liquid only at such low temperatures that chemical reactions may be too slow to sustain life, and lack water's other advantages.

[72][73] Even the simplest members of the three modern domains of life use DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array of RNA and protein molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance and self-replication.

[85] Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form liposomes, double-walled "bubbles", and then reproduce themselves.

[98] Modeled pH and phosphate levels of early Earth carbonate-rich lakes nearly match the conditions used in current laboratory experiments on the origin of life.

[98] Similar to the process predicted by geothermal hot spring hypotheses, changing lake levels and wave action deposited phosphorus-rich brine onto dry shore and marginal pools.

[98] Microbial mats are multi-layered, multi-species colonies of bacteria and other organisms that are generally only a few millimeters thick, but still contain a wide range of chemical environments, each of which favors a different set of microorganisms.

[147] Not long after this primary endosymbiosis of plastids, rhodoplasts and chloroplasts were passed down to other bikonts, establishing a eukaryotic assemblage of phytoplankton by the end of the Neoproterozoic Eon.

[148] Furthermore, contrary to the expectations of the Red Queen hypothesis, Kathryn A. Hanley et al. found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites was significantly higher in sexual geckos than in asexuals sharing the same habitat.

[158] In addition, biologist Matthew Parker, after reviewing numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance, failed to find a single example consistent with the concept that pathogens are the primary selective agent responsible for sexual reproduction in the host.

An alternative view is that sex arose and is maintained as a process for repairing DNA damage, and that the genetic variation produced is an occasionally beneficial byproduct.

[162] Multicellularity evolved independently in organisms as diverse as sponges and other animals, fungi, plants, brown algae, cyanobacteria, slime molds and myxobacteria.

[157] Deuterostomes Ecdysozoa Spiralia Xenacoelomorpha Cnidaria Placozoa Ctenophora Porifera Animals are multicellular eukaryotes,[note 1] and are distinguished from plants, algae, and fungi by lacking cell walls.

For example, brown algae accumulate inorganic mineral antioxidants such as rubidium, vanadium, zinc, iron, copper, molybdenum, selenium and iodine, concentrated more than 30,000 times more than in seawater.

[citation needed] When plants and animals began to enter rivers and land about 500 Ma, environmental deficiency of these marine mineral antioxidants was a challenge to the evolution of terrestrial life.

[202] Lichens, which are symbiotic combinations of a fungus (almost always an ascomycete) and one or more photosynthesizers (green algae or cyanobacteria),[215] are also important colonizers of lifeless environments,[202] and their ability to break down rocks contributes to soil formation where plants cannot survive.

Life on land requires plants to become internally more complex and specialized: photosynthesis is most efficient at the top; roots extract water and nutrients from the ground; and the intermediate parts support and transport.

[222] However, some earlier trace fossils from the Cambrian-Ordovician boundary about 490 Ma are interpreted as the tracks of large amphibious arthropods on coastal sand dunes, and may have been made by euthycarcinoids,[223] which are thought to be evolutionary "aunts" of myriapods.

[225] Arthropods were well pre-adapted to colonise land, because their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.

[228] Osteolepiformes Panderichthyidae Obruchevichthidae Acanthostega Ichthyostega Tulerpeton Early labyrinthodonts Anthracosauria Amniotes Tetrapods, vertebrates with four limbs, evolved from other rhipidistian fish over a relatively short timespan during the Late Devonian (370 to 360 Ma).

Iodine and T4/T3 stimulate the amphibian metamorphosis and the evolution of nervous systems transforming the aquatic, vegetarian tadpole into a "more evolved" terrestrial, carnivorous frog with better neurological, visuospatial, olfactory and cognitive abilities for hunting.

Instead, they write, eusociality evolves only in species that are under strong pressure from predators and competitors, but in environments where it is possible to build "fortresses"; after colonies have established this security, they gain other advantages through co-operative foraging.

[261] The idea that, along with other life forms, modern-day humans evolved from an ancient, common ancestor was proposed by Robert Chambers in 1844 and taken up by Charles Darwin in 1871.

[266] There is also debate about whether anatomically modern humans had an intellectual, cultural and technological "Great Leap Forward" under 40,000–50,000 years ago and, if so, whether this was due to neurological changes that are not visible in fossils.