Executive Order 9066

"This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland—resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

February 19, 1942.Originating from a proclamation that was signed on the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, December 7, 1941, Executive Order 9066 was enacted by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to strictly regulate the actions of Japanese Americans in the United States.

In addition, during the crucial period after Pearl Harbor the president had failed to speak out for the rights of Japanese Americans despite the urgings of advisors such as John Franklin Carter.

During the same period, Roosevelt rejected the recommendations of Attorney General Francis Biddle and other top advisors, who opposed the incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Notably, in a 1943 letter, Attorney General Francis Biddle reminded Roosevelt that "You signed the original Executive Order permitting the exclusions so the Army could handle the Japs.

Authored by War Department official Karl Bendetsen—who would later be promoted to Director of the Wartime Civilian Control Administration and oversee the incarceration of Japanese Americans[9]—the law made violations of military orders a misdemeanor punishable by up to $5,000 in fines and one year in prison.

"[11] As a result, approximately 112,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were evicted from the West Coast of the continental United States and held in American relocation camps and other confinement sites across the country.

Nevertheless, the tremendous cost, including the diversion of ships from the front lines, as well as the quiet resistance of the local military commander General Delos Emmons, made this proposal impractical and Japanese Americans in Hawaii were never incarcerated.

This fact supported the government's eventual conclusion that the mass removal of ethnic Japanese from the West Coast was motivated by reasons other than "military necessity.

Racially discriminatory laws prevented Asian Americans from owning land, voting, testifying against whites in court, and set up other restrictions.

[15] In early 1941, President Roosevelt secretly commissioned a study to assess the possibility that Japanese Americans would pose a threat to U.S. security.

"For the most part," the Munson Report said, "the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.

"[14] A second investigation started in 1940, written by Naval Intelligence officer Kenneth Ringle and submitted in January 1942, likewise found no evidence of fifth column activity and urged against mass incarceration.

[17] Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson was responsible for assisting relocated people with transport, food, shelter, and other accommodations and delegated Colonel Karl Bendetsen to administer the removal of West Coast Japanese.

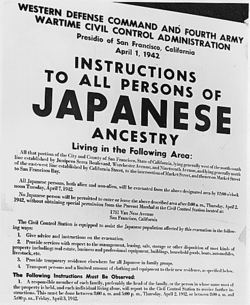

[3] Over the spring of 1942, General John L. DeWitt issued Western Defense Command orders for Japanese Americans to present themselves for removal.

The "evacuees" were taken first to temporary assembly centers, requisitioned fairgrounds and horse racing tracks where living quarters were often converted livestock stalls.

[18] In 1943 and 1944, Roosevelt did not release those incarcerated in the camps despite the urgings of Attorney General Francis Biddle, Secretary of Interior Harold L. Ickes.

On the battlefield and at home the names of Japanese Americans have been and continue to be written in history for the sacrifices and the contributions they have made to the well-being and to the security of this, our common Nation.

In December 1982, the CWRIC issued its findings in Personal Justice Denied, concluding that the incarceration of Japanese Americans had not been justified by military necessity.

The Commission recommended legislative remedies consisting of an official Government apology and redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; a public education fund was set up to help ensure that this would not happen again (Pub.

[25] After the signing of Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, all Japanese Americans were required to be removed from their homes and moved into military camps as a matter of national security.

Instead, Korematsu had plastic surgery to alter the appearance of his eyes and changed his name to Clyde Sarah, claiming Spanish and Hawaiian heritage.

[28] University of Washington student, Gordon Hirabayashi, refused to abide by the order in an act of civil disobedience, resulting in his arrest.

[34] Korematsu v. United States was officially overturned in 2018, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor, describing the case as "gravely wrong the day it was decided.

"[35] February 19, the anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066, is now the Day of Remembrance, an annual commemoration of the unjust incarceration of the Japanese-American community.