Exemptions for fracking under United States federal law

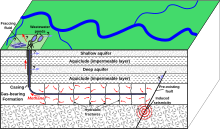

The process to extract oil and natural gas begins with thousands of gallons of water, mixed with a slurry of chemicals, some of which are undisclosed.

This liquid mixture is then forced into well casings under high pressure, and then is horizontally injected into bedrock to create cracks or fissures.

The six regulated criteria pollutants include: particulate matter, lead, ozone, NOx, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide.

[2] All pollutant levels are calculated by associated health risks that would harm the most sensitive subgroup of people, which are considered to be inner city children.

[5] Most oil and gas production sites are not required to obtain a Title V permit because their emissions threshold is just slightly below the categorical statutory definition.

In addition to not having to obtain a Title V permit, the oil and gas exploration and production wells are exempt from the "Aggregation Rule" within the definition of "major source" as defined under the act, essentially to be unregulated under this federal statute.

[8][9] One of the major mechanisms for implementing this statute was to create a permitting process for all discharging methods that involved dumping pollutants into streams, lakes, rivers, wetlands, or creeks.

The National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permitting requirements apply to all phases of the petroleum industry.

[10] In 1987, Congress amended the Act,[11] requiring the EPA to develop a permitting program for storm water runoff,[12] but the exploration, production, and processing of oil and gas was exempt.

"[13][16] Any discharges containing other than precipitation runoff, such as petroleum or produced wastewater are still subject to criminal prosecution under the Clean Water Act.

[22] The policy was overturned in 1997 by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, which ruled that "hydraulic fracturing activities constitute underground injection according to Section C of the SDWA.

The EPA responded with a study of potential and actual impacts of hydraulic fracturing of coalbed methane wells on drinking water, published in 2004.

Section 7.4 of the report "concluded that the injection of hydraulic fracturing fluids into coalbed methane wells poses little or no threat to USDWs and does not justify additional study at this time."

If the assessment determines that the federal action may significantly alter the environment, then an environmental impact statement (EIS) is required.

[26][27] The Energy Policy Act of 2005 created a rebuttable presumption that certain oil and gas related activities authorized by the U.S. Department of the Interior in managing public lands, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture in managing National Forest System lands are subject to a "categorical exclusion" under NEPA, and do not require an EIS, unless it can be demonstrated that they pose a risk to the environment,[6][28] Congress specified five circumstances for which there would be such a rebuttable presumption that an additional EIS is not required: 1.

[29]Other than for the exclusions listed above, federal agencies are required by NEPA to do Environmental Impact Statements to evaluate any oil and gas activities which have the potential to seriously affect the environment.

"[33] Subtitle C of RCRA gives the EPA the authority to regulate the generation, transport, treatment, storage and disposal of all deemed hazardous waste.

The Act requires federal, state, local governments and Indian tribes to inform the public of hazardous and toxic chemicals being used or stored at facilities, their use, and any release into the environment.

[6] The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, also known as Superfund was enacted in 1980 to clean up sites where toxic or hazardous substances have been dumped into the environment.

"Moreover, if the petroleum product and an added hazardous substance are so commingled that, as a practical matter, they cannot be separated, then the entire oil spill is subject to CERCLA response authority."

[44] Despite the petroleum exemption, the EPA has exercised its power under CERCLA to intervene where it considers oil and gas operations to pose "imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare."

These factors include: insufficient pre- and post-fracturing data on the quality of drinking water resources; the paucity of long-term systematic studies; the presence of other sources of contamination precluding a definitive link between hydraulic fracturing activities and an impact; and the inaccessibility of some information on hydraulic fracturing activities and potential impacts.