Exhumation and reburial of Richard III of England

Taking these findings into account along with other historical, scientific and archaeological evidence, the University of Leicester announced on 4 February 2013 that it had concluded beyond reasonable doubt that the skeleton was that of Richard III.

The Lord Mayor Herrick built a mansion close to Friary Lane, on a site now buried under the modern Grey Friars Street, and turned the rest of the land into gardens.

[14] The cartographer and antiquarian John Speed wrote in his Historie of Great Britaine (1611) that local tradition held that Richard's body had been "borne out of the City, and contemptuously bestowed under the end of Bow-Bridge, which giveth passage over a branch of Soare upon the west side of the town.

[16] The writer Audrey Strange suggests that the account may be a confused retelling of desecration of the remains of John Wycliffe in nearby Lutterworth in 1428, when a mob disinterred him, burned his bones and threw them into the River Swift.

[17] The independent British historian John Ashdown-Hill proposes that Speed made a mistake over the location of Richard's grave and invented the story to account for its absence.

If Speed had been to Herrick's property he would surely have seen the commemorative pillar and gardens, but instead he reported that the site was "overgrown with nettles and weeds"[18] and there was no trace of Richard's grave.

[18] Another local legend arose about a stone coffin that supposedly held Richard's remains, which Speed wrote was "now made a drinking trough for horses at a common Inn".

A coffin certainly seems to have existed; John Evelyn recorded it on a visit in 1654, and Celia Fiennes wrote in 1700 that she had seen "a piece of his tombstone [sic] he lay in, which was cut out in exact form for his body to lie in; it remains to be seen at ye Greyhound [Inn] in Leicester but is partly broken."

Herrick's mansion was demolished in 1871, the present Grey Friars Street was laid through the site in 1873, and more commercial developments, including the Leicester Trustee Savings Bank, were built.

In 1975 an article by Audrey Strange was published in the society's journal, The Ricardian, suggesting that his remains were buried under Leicester City Council's car park.

[28] Three years later, writer Annette Carson, in her book Richard III: The Maligned King (the History Press 2008, 2009, page 270), published her independent conclusion that his body probably lay under the car park.

[49] After the exhumation, work continued in the trenches over the following week, before the site was covered with soil to protect it from damage and re-surfaced to restore the car park and playground to their former condition.

The positive indicators were that the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; it had severe scoliosis of the spine, possibly making one shoulder higher than the other.

[54] Ashdown-Hill's research came about as a result of a challenge in 2003 to provide a DNA sequence for Richard's sister Margaret, to identify bones found in her burial place, the Franciscan priory church in Mechelen, Belgium.

[64] Michael Hicks, a Wars of the Roses historian, was particularly critical of the use of the mitochondrial DNA to argue that the body is Richard III's, stating that "any male sharing a maternal ancestress in the direct female line could qualify".

These include the fact that the location of the grave matches the information provided by John Rous, and that the nature of the skeleton – the age of the man, his build, injuries and scoliosis – is in agreement with historical accounts...

[70]An osteological examination of the bones showed them to be in generally good condition and largely complete except for the missing feet, which may have been destroyed by Victorian building work.

The wounds were made from behind on the back and buttocks while they were exposed to the elements, consistent with the contemporary descriptions of Richard's naked body being tied across a horse with the legs and arms dangling down on either side.

Although it was probably visible in making his right shoulder higher than the left and reducing his apparent height, it did not preclude an active lifestyle, and would not have caused what modern medicine describes as a "hunchback".

From the isotope analysis of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen in the teeth and bones the researchers discovered the diet included much freshwater fish and exotic birds such as swan, crane, and heron, and a vast quantity of wine – all items at the high end of the luxury market.

[86][87][88] The identification was based on mitochondrial DNA evidence, soil analysis, dental tests, and physical characteristics of the skeleton consistent with contemporary accounts of Richard's appearance.

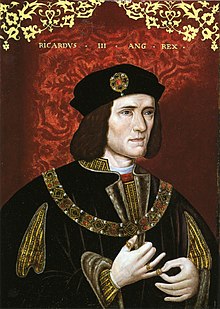

"[86] Caroline Wilkinson, Professor of Craniofacial Identification at the University of Dundee, led the project to reconstruct the face, commissioned by the Richard III Society.

However, Y chromosome DNA inherited via the male line found no link with five other claimed living relatives, indicating that at least one "false-paternity event" occurred in the generations between Richard and these men.

[91] The story of the excavation and subsequent scientific investigation was told in a Channel 4 documentary, Richard III: The King in the Car Park, broadcast on 4 February 2013.

[100] The choice of burial site proved controversial and proposals were made for Richard to be buried in places which some felt were more fitting for a Roman Catholic and Yorkist monarch.

"[102] After legal action brought by the "Plantagenet Alliance", a group representing claimed descendants of Richard's siblings, his final resting place remained uncertain for nearly a year.

Mathematician Rob Eastaway calculated that Richard III's siblings may have millions of living descendants, saying that "we should all have the chance to vote on Leicester versus York".

[107] In August 2013, Mr. Justice Haddon-Cave granted permission for a judicial review since the original burial plans ignored the common law duty "to consult widely as to how and where Richard III's remains should appropriately be reinterred".

[126] The council announced it would create a permanent attraction and subsequently spent £850,000 to buy the freehold of St Martin's Place, formerly part of Leicester Grammar School, in Peacock Lane, across the road from the cathedral.

In contrast to England where, with the possible exceptions of Henry I and Edward V, all the gravesites of English and British monarchs since the 11th century have now been discovered, in Norway about 25 medieval kings are buried in unmarked graves around the country.