Expulsion of Jews from Spain

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Christian anti-Judaism in the West had intensified, which was reflected in the harsh anti-Jewish measures agreed at the Fourth Council of the Lateran called in 1215 by Pope Innocent III.

The good times of the Spain of the three religions had coincided with a phase of territorial, demographic, and economic expansion, in which Jews and Christians did not compete in the labor market: both the former and the latter had contributed to the general prosperity and shared their benefits.

As a result of the massacres of 1391 and the measures that followed, by 1415 more than half of the Jews of the crowns of Castile and Aragon had renounced Mosaic law and had been baptized, including many rabbis and important members of the community.

[37] The situation in which the Jews lived, according to Joseph Perez, posed two problems: "As subjects and vassals of the king, the Jews had no guarantee for the future – the monarch could at any time close the autonomy of the aljamas or require new Most important taxes"; and, above all, "in these late years of the Middle Ages, when a state of modern character was being developed, there could be no question of a problem of immense importance: was the existence of separate and autonomous communities compatible with the demands of a modern state?

According to Joseph Perez, it is a proven fact that, among those who converted to escape the blind furor of the masses in 1391, or by the pressure of the proselytizing campaigns of the early fifteenth century, some clandestinely returned to their old faith when it seemed that the danger had passed, of which it is said that they "Judaized".

He also points out that when a convert was accused of Judaizing, in many cases the "proofs" that were brought were, in fact, cultural elements of his Jewish ancestry – such as treating Saturday, not Sunday, as the day of rest – or the lack of knowledge of the new faith, such as not knowing the creed or eating meat during Lent.

After receiving these reports, the monarchs applied to Pope Sixtus IV for authorization to name a number of inquisitors in their kingdom, which the pontiff agreed to in his bull Exigit sincerae devotionis of 1 November 1478.

But in the Cortes de Toledo of 1480, they decided to go much further to fulfill these norms: to force the Jews to live in separate quarters, where they could not leave except during daytime to carry out their professional occupations.

[50] The text approved by the Cortes, which also applied to the Muslims of the region, read as follows:[51] We send to the aljamas of the said Jews and Moors: that each of them be put in said separation [by] such procedure and such order that within the said term of the said two years they [shall] have the said houses of their separation, and live and die in them, and henceforth not have their dwellings among the Christians or elsewhere outside the designated areas and places that have been assigned to the said Jewish and Moorish quarters.The decision of the kings approved by the Courts of Toledo had antecedents, since Jews already had been confined in some Castilian localities like Cáceres or Soria.

There are doubts as to whether the order was strictly enforced, since at the time of the final expulsion in 1492 some chroniclers speak of the fact that 8,000 families of Andalusia embarked in Cadiz and others in Cartagena and the ports of the Crown of Aragon.

[57] According to Julio Valdeón, the decision to expel the Jews from Andalusia also obeyed "the desire to move them away from the border between the crown of Castile and the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, the scene, during the 1480s and the first years of the 1490s, of the war that ended with the disappearance of the last stronghold of peninsular Islam.

[61] The Catholic Monarchs had precisely entrusted to the inquisitor general Tomás de Torquemada and its collaborators the writing of the decree fixing to them, according to the historian Luis Suarez, three previous conditions which would be reflected in the document: to justify the expulsion by charging Jews with two sufficiently serious offenses – usury and "heretical practice"; That there should be sufficient time for Jews to choose between baptism or exile; And that those who remained faithful to the Mosaic law could dispose of their movable and immovable property, although with the provisos established by the laws: they could not take either gold, silver, or horses.

As the historian Luis Suárez pointed out, the Jews had "four months to take the most terrible decision of their lives: to abandon their faith to be integrated in it [in the kingdom, in the political and civil community], or leave the territory in order to preserve it.

Many others, in order not to deprive themselves of the country where they were born and not to sell their goods at that time at lower prices, were baptized.The most outstanding Jews, with few exceptions such as that of Isaac Abravanel, decided to convert to Christianity.

A chronicler of the time attests:[69] They sold and bargained away everything they could of their estates ... and in everything there were sinister ventures, and the Christians got their estates, very many and very rich houses and inheritances, for few monies; and they went about begging with them, and found not one to buy them, and gave a house for an ass and a vine for a little cloth or linen because they could not bring forth gold or silver.They also had serious difficulties in recovering money lent to Christians because either the repayment term was after August 10, the deadline for their departure, or many of the debtors claimed "usury fraud," knowing that the Jews would not have time for the courts to rule in their favor.

This is how Andrés Bernaldez, pastor of Los Palacios, describes the time when the Jews had to "abandon the lands of their birth":[72] All the young men and daughters who were twelve years old were married to each other, for all the females of this age above were in the shadow and company of husbands...

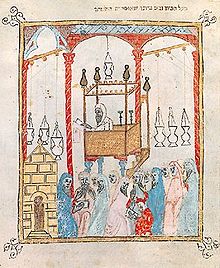

They came out of the lands of their birth, big and small children, old and young, on foot and men on asses and other beasts, and on wagons, and continued their journeys each to the ports where they were to go; and went by the roads and fields where they went with many works and fortunes; some falling, others rising, others dying, others being born, others becoming sick, that there was no Christian that did not feel their pain, and always invited them to baptism, and some, with grief, converted and remained, but very few, and the rabbis worked them up and made the women and young men sing and play tambourines.In the Castillian version of the Alhambra Decree, reference is made exclusively to religious motives.

"[74] Finally, the reason for deciding to expel the entire Jewish community, and not just those of its members who allegedly wanted to "pervert" the Christians, is explained:[66][73] Because when some serious and detestable crime is committed by some college or university [i.e. some corporation and community], it is reason that such college or university be dissolved, and annihilated and the younger ones by the elders and for each other to be punished and that those who pervert the good and honest living of cities and towns by a contagion, that can harm others, be expelled.As highlighted Julio Valdeón, "undoubtedly the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian site is one of the most controversial issues of all that have happened throughout the history of Spain."

Among the monarchs' trusted men were several who belonged to this group, such as the confessor of the queen friar Hernando de Talavera, the steward Andrés Cabrera, the treasurer of the Santa Hermandad Abraham Senior, or Mayr Melamed and Isaac Abarbanel, without counting the Jewish doctors that attended them.

[77] Current historians prefer to place expulsion in the European context, and those such as Luis Suárez Fernández or Julio Valdeón highlight that the Catholic Monarchs were, in fact, the last of the sovereigns of the great western European states to decree expulsion – the Kingdom of England did it in 1290, the Kingdom of France in 1394; in 1421 the Jews were expelled from Vienna; in 1424 from Linz and of Colonia; in 1439 from Augsburg; in 1442 from Bavaria; in 1485 from Perugia; in 1486 from Vicenza; in 1488 from Parma; in 1489 from Milan and Luca; in 1493 from Sicily; in 1494 from Florence; in 1498 from Provence...-.

[78] The objective of all of them was to achieve unity of faith in their states, a principle that would be defined in the 16th century with the maxim "cuius regio, eius religio," i.e., that the subjects should profess the same religion as their prince.

Pérez adds, "The University of Paris congratulated Spain for having carried out an act of good governance, an opinion shared by the best minds of the time (Machiavelli, Guicciardini, Pico della Mirandola)... [...] it was the so-called medieval coexistence that was strange to Christian Europe.

[84] On the other hand, Joseph Pérez, following Luis Suárez, places the expulsion within the context of the construction of the "modern State," which requires greater social cohesion based on the unity of faith to impose its authority on all groups and individuals in the kingdom.

For this reason, it is not by chance, Pérez warns, that only three months after having eliminated the last Muslim stronghold on the peninsula with the conquest of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, the monarchs decreed the expulsion of the Jews.

[92] Although the vast majority of conversos simply assimilated into the Catholic dominant culture, a minority continued to practice Judaism in secret, gradually migrating throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, mainly to areas where Sephardic communities were already present as a result of the Alhambra Decree.

As Joseph Pérez has pointed out, "in view of the published literature on taxation and economic activities, there is no doubt that the Jews were no longer a source of relevant wealth, neither as bankers nor as renters nor as merchants who conducted business at an international level.

"[95] An issue of the Amsterdam Gazette published in the Netherlands on September 12, 1672, and preserved at Beth Hatefutsoth evidences interest by the Jewish community in what was happening at that time in Madrid, and it presents the news in Spanish, 180 years after the expulsion.

"[86] Regarding Judeo-Spanish (also known as Ladino) as a socio-cultural and identity phenomenon, Garcia-Pelayo and Gross wrote in 1977: It is said of the Jews expelled from Spain in the 15th century that they preserve the language and the Spanish traditions in the East.

The expulsion of the Jews [...] sent a large number of families out of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly from Andalusia and Castile, to settle in the eastern Mediterranean countries dominated by the Turks, where they formed colonies which have survived to this day, especially in Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria [...].

Its phonetics present some archaic but not degenerate forms; Its vocabulary offers countless loan words from Hebrew, Greek, Italian, Arabic, Turkish, according to the countries of residence.