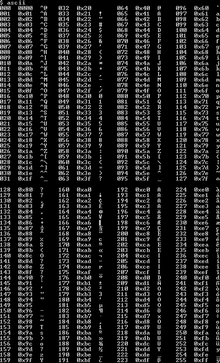

Extended ASCII

There is no formal definition of "extended ASCII", and even use of the term is sometimes criticized,[1][2][3] because it can be mistakenly interpreted to mean that the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) had updated its ANSI X3.4-1986 standard to include more characters, or that the term identifies a single unambiguous encoding, neither of which is the case.

However, extended ASCII remains important in the history of computing, and supporting multiple extended ASCII character sets required software to be written in ways that made it much easier to support the UTF-8 encoding method later on.

Of the 27=128 codes, 33 were used for controls, and 95 carefully selected printable characters (94 glyphs and one space), which include the English alphabet (uppercase and lowercase), digits, and 31 punctuation marks and symbols: all of the symbols on a standard US typewriter plus a few selected for programming tasks.

Some popular peripherals only implemented a 64-printing-character subset: Teletype Model 33 could not transmit "a" through "z" or five less-common symbols (`, {, |, }, and ~).

The ASCII character set is barely large enough for US English use, lacks many glyphs common in typesetting, and is far too small for universal use.

Programming languages however had assigned meaning to many of the replaced characters, work-arounds were devised such as C three-character sequences ?

[4] Languages with dissimilar basic alphabets could use transliteration, such as replacing all the Latin letters with the closest match Cyrillic letters (resulting in odd but somewhat readable text when English was printed in Cyrillic or vice versa).

Thus encodings which covered all the major Western European (and Latin American) languages and more could be made.

There were eventually attempts at cooperation or coordination by national and international standards bodies in the late 1990s, but manufacturer-proprietary sets remained the most popular by far, primarily because the international standards excluded characters popular in or peculiar to specific cultures.

Various proprietary modifications and extensions of ASCII appeared on mainframe computers[a] and minicomputers – especially in universities, to meed their need to support teaching of mathematics, science and languages.

The larger character set made it possible to create documents in a combination of languages such as English and French (though French computers usually use code page 850), but not, for example, in English and Greek (which required code page 737).

The added characters included "curly" quotation marks, the em dash, the euro sign, and the French and Finnish letters from ISO-8859-15.

Choosing the wrong encoding causes the display of often wildly-incorrect characters, known by the Japanese term mojibake.