Female genital mutilation

[9] Adverse health effects depend on the type of procedure; they can include recurrent infections, difficulty urinating and passing menstrual flow, chronic pain, the development of cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth, and fatal bleeding.

[35] In 2017, during an international meeting of 98 FGM experts, which included physicians, social scientists, policymakers, and activists from 23 countries, a majority of the participants advocated for the revision of FGM/C classifications proposed by the WHO and other UN agencies.

[46] In Somalia, according to Edna Adan Ismail, the child squats on a stool or mat while adults pull her legs open; a local anaesthetic is applied if available: The element of speed and surprise is vital and the circumciser immediately grabs the clitoris by pinching it between her nails aiming to amputate it with a slash.

[k][52] Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III: The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months.

In a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara, over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts were found to have vesicovaginal fistulae (holes that allow urine to seep into the vagina).

According to the study, FGM was associated with an increased risk to the mother of damage to the perineum and excessive blood loss, as well as a need to resuscitate the baby, and stillbirth, perhaps because of a long second stage of labour.

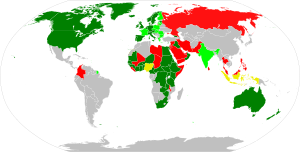

[85]: 2 Smaller studies or anecdotal reports suggest that various types of FGM are also practised in various circumstances in Colombia, Jordan, Oman, Palestine,[88] Saudi Arabia,[89][90] Malaysia,[91] the United Arab Emirates,[4] India,[92] and among Kurdish communities in Iran[88] but there are no representative data on the prevalence in these countries.

[4] As of 2023[update], UNICEF reported that "The highest levels of support for FGM can be found in Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, the Gambia, Somalia, and Egypt, where more than half of the female population thinks the practice should continue".

[114][p] Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes wrote in 1975 that educated Sudanese men who did not want their daughters to be infibulated (preferring clitoridectomy) would find the girls had been sewn up after the grandmothers arranged a visit to relatives.

[122] Fuambai Ahmadu, an anthropologist and member of the Kono people of Sierra Leone, who in 1992 underwent clitoridectomy as an adult during a Sande society initiation, argued in 2000 that it is a male-centred assumption that the clitoris is important to female sexuality.

[125] The local preference for dry sex causes women to introduce substances into the vagina to reduce lubrication, including leaves, tree bark, toothpaste and Vicks menthol rub.

Lala Baldé, president of a women's association in Medina Cherif, a village in Senegal, told Mackie in 1998 that when girls fell ill or died, it was attributed to evil spirits.

[136] The American non-profit group Tostan, founded by Molly Melching in 1991, introduced community-empowerment programs in several countries that focus on local democracy, literacy, and education about healthcare, giving women the tools to make their own decisions.

[147][u] Islamic scholars Abū Dāwūd and Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal reported that Muhammad said circumcision was a "law for men and a preservation of honor for women",[148] however some regard this Hadith as daʻīf (weak).

Gerry Mackie has suggested that, because FGM's east–west, north–south distribution in Africa meets in Sudan, infibulation may have begun there with the Meroite civilization (c. 800 BCE – c. 350 CE), before the rise of Islam, to increase confidence in paternity.

Citing the Australian pathologist Grafton Elliot Smith, who examined hundreds of mummies in the early 20th century, Knight writes that the genital area may resemble Type III because during mummification the skin of the outer labia was pulled toward the anus to cover the pudendal cleft, possibly to prevent a sexual violation.

From 1966 until 1989, he performed "love surgery" by cutting women's pubococcygeus muscle, repositioning the vagina and urethra, and removing the clitoral hood, thereby making their genital area more appropriate, in his view, for intercourse in the missionary position.

Protestant missionaries in British East Africa (present-day Kenya) began campaigning against FGM in the early 20th century, when Dr. John Arthur joined the Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) in Kikuyu.

[189] In 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council began referring to FGM as the "sexual mutilation of women", and a person's stance toward the practice became a test of loyalty, either to the Christian churches or to the Kikuyu Central Association.

[191] When Hulda Stumpf, an American missionary who opposed FGM in the girls' school she helped to run, was murdered in 1930, Edward Grigg, the governor of Kenya, told the British Colonial Office that the killer had tried to circumcise her.

At the mission in Tumutumu, Karatina, where Marion Scott Stevenson worked, a group calling themselves Ngo ya Tuiritu ("Shield of Young Girls"), the membership of which included Raheli Warigia (mother of Gakaara wa Wanjaũ), wrote to the Local Native Council of South Nyeri on 25 December 1931: "[W]e of the Ngo ya Tuiritu heard that there are men who talk of female circumcision, and we get astonished because they (men) do not give birth and feel the pain and even some die and even others become infertile, and the main cause is circumcision.

In 1956 in Meru, eastern Kenya, when the council of male elders (the Njuri Nchecke) announced a ban on FGM in 1956, thousands of girls cut each other's genitals with razor blades over the next three years as a symbol of defiance.

[204]In 1975, Rose Oldfield Hayes, an American social scientist, became the first female academic to publish a detailed account of FGM, aided by her ability to discuss it directly with women in Sudan.

[3] In December 1993, the United Nations General Assembly included FGM in resolution 48/104, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, and from 2003 sponsored International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, held every 6 February.

[219][220] UNICEF began in 2003 to promote an evidence-based social norms approach, using ideas from game theory about how communities reach decisions about FGM, and building on the work of Gerry Mackie on the demise of footbinding in China.

[222][af] In 2008 several UN bodies recognized FGM as a human-rights violation,[224] and in 2010 the UN called upon healthcare providers to stop carrying out the procedures, including reinfibulation after childbirth and symbolic nicking.

[229]: 2 The first FGM conviction in the US was in 2006, when Khalid Adem, who had emigrated from Ethiopia, was sentenced to ten years for aggravated battery and cruelty to children after severing his two-year-old daughter's clitoris with a pair of scissors.

[ai] Canada recognized FGM as a form of persecution in July 1994, when it granted refugee status to Khadra Hassan Farah, who had fled Somalia to avoid her daughter being cut.

The feminist theorist Obioma Nnaemeka, herself strongly opposed to FGM, argued in 2005 that renaming the practice female genital mutilation had introduced "a subtext of barbaric African and Muslim cultures and the West's relevance (even indispensability) in purging [it]".

[265] Ronán Conroy of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland wrote in 2006 that cosmetic genital procedures were "driving the advance" of FGM by encouraging women to see natural variations as defects.