Faculty of Theology, Old University of Leuven

After repeated requests from the municipal government, from the Duke of Brabant and from Philip the Good, the university received permission to grant theological degrees from Pope Eugene IV on 7 March 1432.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Adrian's successors made a name for themselves by resourcing theology through a renewed study of Augustine.

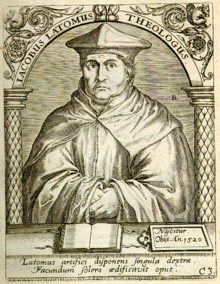

An example of this is seen in Jacobus Latomus's De trium linguarum et studii theologici ratione dialogus, which was published in 1519 as a response to the challenge posed by the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who was active at the Collegium Trilingue in Leuven.

At the same time, the faculty also opposed Martin Luther's thought, by refuting his early writings in a censure published on 7 November 1519.

This theology focused on Augustine's thought regarding grace and creation, and it produced an extremely negative view of humanity in its fallen state.

Later, in the twentieth century, theologians such as Henri de Lubac – in his famous book Surnaturel of 1946 – revived the discussion on the value of Baius' theological opinions.

Jansenius studied the original sources rather than concentrating upon scholastic subtleties in a debate over the ground and efficacy of grace precisely as Pope Clement VIII had demanded.

Jansenius' study of Augustine of Hippo's thought cost many years of work as is reflected in his book Augustinus, which was published posthumously in 1640.

Between 1677 and 1679, the faculty obtained the condemnation, through Pope Innocent XI, of 65 theses drawn from the writings of Jesuit moral theologians.

The faculty became more conciliatory toward the central doctrinal authority in the eighteenth century, becoming a center of Ultramontanism through its dismissal of Gallicanism and Febronianism.

The faculty's reputation was strengthened by its opposition to Joseph II of Austria's religious politics and to the vows imposed on clerics by the French Republic.