The Faerie Queene

In Spenser's "Letter of the Authors", he states that the entire epic poem is "cloudily enwrapped in Allegorical devices", and that the aim of publishing The Faerie Queene was to "fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline".

But despite its title, Cambell's companion in Book IV is actually named Triamond, and the plot does not center on their friendship; the two men appear only briefly in the story.

Book V is centred on the virtue of Justice as embodied in Sir Artegall, who defeats a demagogic giant and mediates several conflicts, including a joust held in honor of Florimell's nuptials.

Departing from Artegall, Spenser presents Prince Arthur's quest to slay the beast Gerioneo in order to restore the lady Belge to her rights.

Book VI is centred on the virtue of Courtesy as embodied in Sir Calidore who is on a mission from the Faerie Queene to slay the Blatant Beast.

After helping reconcile two lovers and taking on the courteous young Tristram as his page, he falls prey to the pleasant distractions of pastoral life and eventually wins the affections of Pastorella away from the ultimately agreeable but somewhat cowardly Coridon.

Calidore rescues his love from the Blatant Beast, capturing and binding the monster, which nonetheless, we are told, eventually escapes to prowl about the world once more to seek the ruin of more reputations.

The Aeneid states that Augustus descended from the noble sons of Troy; similarly, The Faerie Queene suggests that the Tudor lineage can be connected to King Arthur.

She appears in the guise of Gloriana, the Faerie Queen, but also in Books III and IV as the virgin Belphoebe, daughter of Chrysogonee and twin to Amoret, the embodiment of womanly married love.

The world of The Faerie Queene is based on English Arthurian legend, but much of the language, spirit, and style of the piece draw more on Italian epic, particularly Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso and Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered.

Spenser integrates these patterns to focus the meaning of the past on the present, emphasizing the significance of Elizabeth's reign by converting myth into event rather than the other way around.

For instance, the British Chronicle, which Arthur reads in the House of Alma, serves as a poetical equivalent for factual history despite its partially imaginary nature.

[18] However, marginal notes jotted in early copies of The Faerie Queene suggest that Spenser's contemporaries were unable to come to a consensus about the precise historical referents of the poem's "myriad figures".

[21] Specific examples include the swine present in Lucifera's castle who embodied gluttony,[22] and Duessa, the deceitful crocodile who may represent Mary, Queen of Scots, in a negative light.

[23] The House of Busirane episode in Book III in The Faerie Queene is partially based on an early modern English folktale called "Mr. Fox's Mottos".

[32] Throughout The Faerie Queene, virtue is seen as "a feature for the nobly born" and within Book VI, readers encounter worthy deeds that indicate aristocratic lineage.

[33] By giving the Salvage Man a "frightening exterior", Spenser stresses that "virtuous deeds are a more accurate indication of gentle blood than physical appearance.

During his initial encounter with Arthur, Turpine "hides behind his retainers, chooses ambush from behind instead of direct combat, and cowers to his wife, who covers him with her voluminous skirt".

[34] Scholars believe that this characterization serves as "a negative example of knighthood" and strives to teach Elizabethan aristocrats how to "identify a commoner with political ambitions inappropriate to his rank".

Elizabethans learned to embrace religious studies in petty school, where they "read from selections from the Book of Common Prayer and memorized Catechisms from the Scriptures".

[38] In Book I of The Faerie Queene the discussion of the path to salvation begins with original sin and justification, skipping past initial matters of God, the Creeds, and Adam's fall from grace.

[42] Spenser's characters embody Elizabethan values, highlighting political and aesthetic associations of Tudor Arthurian tradition in order to bring his work to life.

While Spenser respected British history and "contemporary culture confirmed his attitude",[42] his literary freedom demonstrates that he was "working in the realm of mythopoeic imagination rather than that of historical fact".

[42] In fact, Spenser's Arthurian material serves as a subject of debate, intermediate between "legendary history and historical myth" offering him a range of "evocative tradition and freedom that historian's responsibilities preclude".

[46] The tradition begun by Geoffrey of Monmouth set the perfect atmosphere for Spenser's choice of Arthur as the central figure and natural bridegroom of Gloriana.

[48] Samuel Johnson found Spencer's writings "a useful source for obsolete and archaic words", but also asserted that "in affecting the ancients Spenser writ no language".

[49] Herbert Wilfred Sugden argues in The Grammar of Spenser's Faerie Queene that the archaisms reside "chiefly in vocabulary, to a high degree in spelling, to some extent in the inflexions, and only slightly in the syntax".

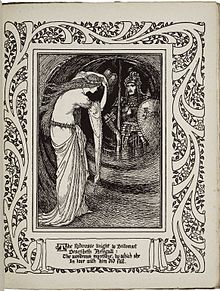

[57] Additionally, Walter Crane illustrated a six-volume collection of the complete work, published 1897, considered a great example of the Arts and Crafts movement.

[58][59] In "The Mathematics of Magic", the second of Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp's Harold Shea stories, the modern American adventurers Harold Shea and Reed Chalmers visit the world of The Faerie Queene, where they discover that the greater difficulties faced by Spenser's knights in the later portions of the poem are explained by the evil enchanters of the piece having organized a guild to more effectively oppose them.

A considerable part of Elizabeth Bear's "Promethean Age" series[60] takes place in a Kingdom of Faerie which is loosely based on the one described by Spenser.