Syncope (medicine)

Syncope ((syncopeⓘ), commonly known as fainting or passing out, is a loss of consciousness and muscle strength characterized by a fast onset, short duration, and spontaneous recovery.

[1] There are sometimes symptoms before the loss of consciousness such as lightheadedness, sweating, pale skin, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, or feeling warm.

[1][3] Psychiatric causes can also be determined when a patient experiences fear, anxiety, or panic; particularly before a stressful event, usually medical in nature.

[1] This may occur from either a triggering event such as exposure to blood, pain, strong feelings or a specific activity such as urination, vomiting, or coughing.

[1] This may occur from either a triggering event such as exposure to blood, pain, strong feelings, or a specific activity such as urination, vomiting, or coughing.

This is set in motion via the adrenergic (sympathetic) outflow from the brain, but the heart is unable to meet requirements because of the low blood volume, or decreased return.

The high (ineffective) sympathetic activity is thereby modulated by vagal (parasympathetic) outflow leading to excessive slowing of heart rate.

These consist of light-headedness, confusion, pallor, nausea, salivation, sweating, tachycardia, blurred vision, and sudden urge to defecate among other symptoms.

Another evolutionary psychology view is that some forms of fainting are non-verbal signals that developed in response to increased inter-group aggression during the paleolithic.

A 2023 study[14][15] identified neuropeptide Y receptor Y2 vagal sensory neurons (NPY2R VSNs) and the periventricular zone (PVZ) as a coordinated neural network participating in the cardioinhibitory Bezold–Jarisch reflex (BJR)[16][17] regulating fainting and recovery.

Syncope may be caused by specific behaviors including coughing, urination, defecation, vomiting, swallowing (deglutition), and following exercise.

[3] Manisty et al. note: "Deglutition syncope is characterised by loss of consciousness on swallowing; it has been associated not only with ingestion of solid food, but also with carbonated and ice-cold beverages, and even belching.

[citation needed] Long QT syndrome can cause syncope when it sets off ventricular tachycardia or torsades de pointes.

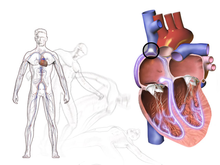

[9] Diseases involving the shape and strength of the heart can be a cause of reduced blood flow to the brain, which increases risk for syncope.

[22] In general, faints caused by structural disease of the heart or blood vessels are particularly important to recognize, as they are warning of potentially life-threatening conditions.

[24] Orthostatic (postural) hypotensive syncope is caused primarily by an excessive drop in blood pressure when standing up from a previous position of lying or sitting down.

[9] Apparently healthy individuals may experience minor symptoms ("lightheadedness", "greying-out") as they stand up if blood pressure is slow to respond to the stress of upright posture.

[citation needed] More serious orthostatic hypotension is often the result of certain commonly prescribed medications such as diuretics, β-adrenergic blockers, other anti-hypertensives (including vasodilators), and nitroglycerin.

[9] Hypoadrenergic orthostatic hypotension occurs when the person is unable to sustain a normal sympathetic response to blood pressure changes during movement despite adequate intravascular volume.

[9] These processes cause the typical symptoms of fainting: pale skin, rapid breathing, nausea, and weakness of the limbs, particularly of the legs.

A number of factors make a heart related cause more likely including age over 35, prior atrial fibrillation, and turning blue during the event.

[34][35] Signs of HCM include large voltages in the precordial leads, repolarization abnormalities, and a wide QRS with a slurred upstroke.

For people with uncomplicated syncope (without seizures and a normal neurological exam) computed tomography or MRI is not generally needed.

[30] Other diseases which mimic syncope include seizure, low blood sugar, certain types of stroke, and paroxysmal spells.

[9][42] While these may appear as "fainting", they do not fit the strict definition of syncope being a sudden reversible loss of consciousness due to decreased blood flow to the brain.

[20] Recommended acute treatment of vasovagal and orthostatic (hypotension) syncope involves returning blood to the brain by positioning the person on the ground, with legs slightly elevated or sitting leaning forward and the head between the knees for at least 10–15 minutes, preferably in a cool and quiet place.

[10] At the appearance of warning signs such as lightheadedness, nausea, or cold and clammy skin, counter-pressure maneuvers that involve gripping fingers into a fist, tensing the arms, and crossing the legs or squeezing the thighs together can be used to ward off a fainting spell.

High risk is anyone who has: congestive heart failure, hematocrit <30%, electrocardiograph abnormality, shortness of breath, or systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg.

[31] It has been shown to be more effective than older syncope risk scores even combined with cardiac biomarkers at predicting adverse events.

The term is derived from the Late Latin syncope, from Ancient Greek συγκοπή (sunkopē) 'cutting up', 'sudden loss of strength', from σύν (sun, "together, thoroughly") and κόπτειν (koptein, "strike, cut off").