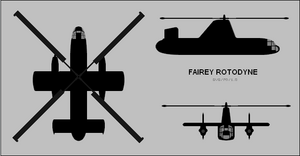

Fairey Rotodyne

[1] A development of the earlier Fairey Jet Gyrodyne, which had established a world helicopter speed record, the Rotodyne featured a tip-jet-powered rotor that burned a mixture of fuel and compressed air bled from two wing-mounted Napier Eland turboprops.

The termination has been attributed to the type failing to attract any commercial orders; this was in part due to concerns over the high levels of rotor tip jet noise generated in flight.

[2] While some progress in Britain had been made prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, wartime priorities placed upon the aviation industry meant that British programmes to develop rotorcraft and helicopters were marginalised at best.

Having little in common with the later Rotodyne, it was characterised by its inventor, Dr JAJ Bennett, formerly chief technical officer of the pre-Second World War Cierva Autogiro Company as an intermediate aircraft designed to combine the safety and simplicity of the autogyro with hovering performance.

[4] The programme was not trouble-free however, a fatal accident involving one of the prototypes occurring in April 1949 due to poor machining of a rotor blade flapping link retaining nut.

[4] The second FB-1 was modified to investigate a tip-jet driven rotor with propulsion provided by propellers mounted at the tip of each stub wing, being renamed the Jet Gyrodyne.

[6] The BEA Bus requirement was met with a variety of futuristic proposals; both practical and seemingly impractical submissions were made by a number of manufacturers.

[6] Fairey had produced multiple arrangements and configurations for the aircraft, typically varying in the powerplants used and the internal capacity; the firm made its first submission to the Ministry on 26 January 1949.

[7] Due to complaints by Armstrong Siddeley that it too was lacking resources, Fairey also proposed the alternative use of engines such as the de Havilland Goblin and the Rolls-Royce Derwent turbojet to drive the forward propellers.

[9] In April 1953, the Ministry of Supply contracted for the building of a single prototype of the Rotodyne Y, powered by the Eland engine, later designated with the serial number XE521, for research purposes.

[5] As contracted, the Rotodyne would have been the largest transport helicopter of its day, seating a maximum of 40 to 50 passengers, while possessing a cruise speed of 150 mph and a range of 250 nautical miles.

The government agreed to maintain funding for the project only if, among other qualifications, Fairey and Napier (through their parent English Electric) contributed to development costs of the Rotodyne and the Eland engine respectively.

The American company Kaman Helicopters also showed strong interest in the project, and was known to have studied it closely as the firm considered the potential for licensed production of the Rotodyne for both civil and military customers.

[13] During 1956, the Defence Research Policy Committee had declared that there was no military interest in the type, which quickly led to the Rotodyne becoming solely reliant upon civil budgets as a research/civil prototype aircraft instead.

[13] After a series of political arguments, proposals, and bargaining; in December 1956, HM Treasury authorised work on both the Rotodyne and Eland engine to be continued until the end of September 1957.

Amongst the demands exerted by the Treasury were that the aircraft had to be both a technical success and would need to acquire a firm order from BEA; both Fairey and English Electric (Napier's parent company) also had to take on a portion of the costs for its development as well.

By January 1959, British European Airways (BEA) announced that it was interested in the purchase of six aircraft, with a possibility of up to 20, and had issued a letter of intent stating such, on the condition that all requirements, including noise levels, were met.

[12] In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies.

Considerable importance was placed upon BEA supporting the Rotodyne by issuing an order; however, the airline refused to procure the aircraft until it was satisfied that guarantees were given over its performance, economy, and noise criteria.

[14] Shortly after Fairey's merger with Westland, the latter was issued a £4 million development contract for the Rotodyne, which was intended to see the type enter service with BEA as a result.

[25] As flight testing with the Rotodyne prototype had proceeded, Fairey had become increasingly dissatisfied with Napier and the Eland engine as progress to improve the latter had been less than expected.

[29] As a result of being unable to resolve the issues with the Eland, Fairey opted to adopt the rival Rolls-Royce Tyne turboprop engine to power the larger Rotodyne Z instead.

According to some of the later proposals, the Rotodyne Z would have had a gross weight of 58,500 lb, an extended rotor diameter of 109 ft, and a tapered wing with a span of 75 ft.[31] However, the Tyne engines were also starting to appear under-powered for the larger design.

[25] Despite the strenuous efforts of Fairey to achieve its support, the expected order from the RAF did not materialise — at the time, the service had no particular interest in the design, being more focused on effectively addressing the issue of nuclear deterrence.

[8][32] The project's final end came when BEA chose to decline placing its own order for the Rotodyne, principally because of its concerns regarding the high-profile tip-jet noise issue.

The one great criticism of the Rotodyne was the noise the tip jets made; however, the jets were only run at full power for a matter of minutes during departure and landing and, indeed, the test pilot Ron Gellatly made two flights over central London and several landings and departures at Battersea Heliport with no complaints being registered,[35] though John Farley, chief test pilot of the Hawker Siddeley Harrier later commented: From two miles away it would stop a conversation.

[38] This effort, however, was insufficient for BEA which, as expressed by Chairman Sholto Douglas, "would not purchase an aircraft that could not be operated due to noise", and the airline refused to order the Rotodyne, which in turn led to the collapse of the project.

[5] It featured an unobstructed rectangular fuselage, capable of seating between 40 and 50 passengers; a pair of double-clamshell doors were placed to the rear of the main cabin so that freight and even vehicles could be loaded and unloaded.