Faith Ringgold

[5]: 27 Her childhood friend, Sonny Rollins, who became a prominent jazz musician, often visited her family and practiced saxophone at their parties.

[5]: 28 Because of her chronic asthma, Ringgold explored visual art as a major pastime through the support of her mother, often experimenting with crayons as a young girl.

'[5]: 24 With all of these influences combined, Ringgold's future artwork was greatly affected by the people, poetry, and music she experienced in her childhood, as well as the racism, sexism, and segregation she dealt with in her everyday life.

She was inspired by the writings of James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka, African art, Impressionism, and Cubism to create the works she made in the 1960s.

Though she received a great deal of attention with these images, many of her early paintings focused on the underlying racism in everyday activities;[16] which made sales difficult, and disquieted galleries and collectors.

[11]: 145 In a 2019 article with Hyperallergic magazine, Ringgold explained that her choice for a political collection comes from the turbulent atmosphere around her: "( ... ) it was the 1960s and I could not act like everything was okay.

[6] Oil paintings like For Members Only, Neighbors, Watching and Waiting, and The Civil Rights Triangle also embody these themes.

The large-scale mural is an anti-carceral work, composed of depictions of women in professional and civil servant roles, representing positive alternatives to incarceration.

He sent a couple of representatives to buy a piece, and they realized, only after the artist suggested they actually read the text on her work, that the stars and stripes of the American flag as depicted also optically incorporated the phrase "DIE NIGGER".

[24] In 2013, Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger was shown in the artist's solo exhibition at ACA Galleries in New York, where it was highlighted by the artist and critic Paige K. Bradley in the first solo show coverage Ringgold had ever received from Artforum[23] up until then, preceding Beau Rutland's own review two months later.

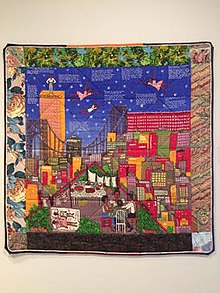

[26] In The French Collection, a multi-paneled series that touches on the truths and mythologies of modernism, Ringgold explored a different solution to overcoming the painful historical legacy of women and men of African descent.

[27] In terms of the place of painting in her practice as whole, the artist considered it her "primary means of expression," as she noted in an interview on the occasion of a retrospective at the New Museum in New York City, from 2022.

In Amsterdam, she visited the Rijksmuseum, which became one of the most influential experiences affecting her mature work, and subsequently, led to the development of her quilt paintings.

In the museum, Ringgold encountered a collection of 14th- and 15th-century Tibetan and Nepali paintings, which inspired her to produce fabric borders around her own work.

[5]: 44–45 Ringgold was also taught the art of quilting in an African-American style by her grandmother,[6] who had in turn learned it from her mother, Susie Shannon, who was a slave.

(1983) depicts the story of Aunt Jemima as a matriarch restaurateur and fictionally revises "the most maligned black female stereotype.

"[34] Another piece, titled Change: Faith Ringgold's Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986), engages the topic of "a woman who wants to feel good about herself, struggling to [the] cultural norms of beauty, a person whose intelligence and political sensitivity allows her to see the inherent contradictions in her position, and someone who gets inspired to take the whole dilemma into an artwork".

[35] It also calls out and redirects of the male gaze, and illustrates the immersive power of historical fantasy and childlike imaginative storytelling.

She later began making dolls with painted gourd heads and costumes (also made by her mother, which subsequently lead her to life-sized soft sculptures).

The sculptures had baked and painted coconuts shell heads, anatomically-correct foam and rubber bodies covered in clothing, and hung from the ceiling on invisible fishing lines.

[40] As many of Ringgold's mask sculptures could also be worn as costumes, her transition from mask-making to performance art was a self-described "natural progression".

[11]: 206 Though art performance pieces were abundant in the 1960s and 1970s, Ringgold was instead inspired by the African tradition of combining storytelling, dance, music, costumes, and masks into one production.

She voiced the opinion of many other African Americans—there was "no reason to celebrate two hundred years of American Independence ... for almost half of that time we had been in slavery".

She described in her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, that her performance pieces were not meant to shock, confuse or anger, but rather "simply another way to tell my story".

[42] In her picture books, Ringgold approached complex issues of racism in straightforward and hopeful ways, combining fantasy and realism to create an uplifting message for children.

Members of the committee demanded that women artists account for fifty percent of the exhibitors and created disturbances at the museum by singing, blowing whistles, chanting about their exclusion, and leaving raw eggs and sanitary napkins on the ground.

In 1970, Ringgold and her daughter Michele Wallace founded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL).

"[47] Ringgold spoke about black representation in the arts in 2004, saying: When I was in elementary school I used to see reproductions of Horace Pippin's 1942 painting called John Brown Going to His Hanging in my textbooks.

[61] The show included three of her murals: The Flag is Bleeding, U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, and Die.

Along with Ringgold, the exhibiting artists included Tschabalala Self, Xaviera Simmons, Romare Bearden, Juana Valdez, Edward Clark, Kevin Beasley, and others.