Fall of Barcelona

The offensive unfolded since late December 1938; the Republicans were offering some resistance, but they were not in position to mount any larger counter-offensive and there was no major battle fought either in western Catalonia or on approaches to Barcelona.

Though after 2 weeks of combat the Nationalists were still no closer than 110 km to Barcelona, their offensive was now progressing along some 150-km long frontline from Tremp at the Pyrenean foothills in the north to Tortosa on the Mediterranean coast in the south.

The Catalan industry, since the summer of 1936 on revolutionary footing, was in decline, yet contemporary scholar concludes that "industria de guerra catalana siguió funcionando relativamente bien hasta el mismísimo final del conflicto".

[21] The press were fairly accurately reporting frontline developments, yet contrary to facts they claimed that their own troops were doing well, remained in excellent spirits and kept inflicting heavy losses upon the enemy.

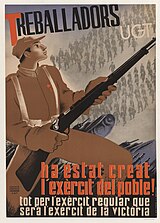

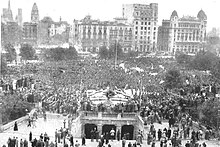

Popular Front parties started publishing repeated calls for males to volunteer for either combat troops or fortification units,[22] though with at best moderate response on the part of the population.

All active political forces represented in Barcelona seemed united behind the governmental policy of resistance and there were no official voices of dissent heard, e.g. about commencing talks on truce or surrender.

Both civilian (Negrín) and military (Rojo) leaders started to consider mounting an ultimate defence line along the Llobregat river, in its lower section flowing directly at the outskirts of Barcelona.

The local Republican advance in Extremadura, commenced on January 5 some 800 km away, was put on equal footing with the Nationalist one in Catalonia and at times even occupied more space in the papers.

Though seemingly scarcely enthusiastic, when interrogated by superiors the recruits declared they were prepared and determined to fight "hasta el final",[51] yet later Rojo wrote that "for the spirit of resistance there had been substituted the idea of salvation.

[59] A number of well-known personalities, including Martínez Barrio, Ramón Lamoneda, Nicolau d'Olwer, Antonio Machado, Manuel Irujo, and Margarita Nelken signed an open letter to the international audience; it falsely claimed that in Santa Coloma de Queralt the Nationalists machine-gunned hundreds of people.

[62] Newspapers published numerous manifestos, declarations and calls to arms; accounts from frontlines featured stories about heroism and sacrifice, highlighting episodes and personalities iconic for Republican advantages.

Nationalist troops, so far most advanced on coastal and central sectors of the front, progressed also north-west of Barcelona, reaching the slopes of Serra de Castelltalat and the outskirts of Calaf, which was taken the same day; they were starting to near approaches to Igualada and Manresa.

The Barcelona press clung to any signs of hope, e.g. referring calls to convene the House of Commons in London or to discuss war atrocities in the League of Nations headquarters in Geneva.

The Nationalists seized Vilafranca del Penedes and Vilanova i la Geltrú in the south and Saint Joan de Mediona and Sant Pere Sacarrera in the centre; all these places were some 40–45 km from Barcelona.

[67] To avoid panic, these activities were kept secret,[68] but since all drivers in service of autonomous government were told to gather at specified points in the city on Monday, January 23,[69] news started to spread.

He issued an order which suspended all industrial and commercial activities in Barcelona for the week starting Monday, January 23; the declared purpose was to enable all employees to take part in fortification works.

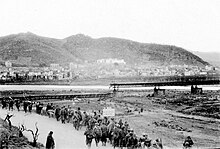

Negrín passed on the information, just received from Rojo, that attempts to mount a last line of resistance along the Llobregat failed and most likely counter-action of Republican troops would be reduced to manoeuvrable defence on the right and the left bank of the river.

[85] Starting early afternoon all institutions, organizations and entities with any vehicles and petrol available – from Institució de les Lletres Catalanes to fábrica aeronáutica Elizalde - were already busy preparing for evacuation, and some inhabitants with improvised means appeared on roads leading north of Barcelona.

[86] CNT, FAI and Juventudes Libertarias staged a plenary session; they decided to move to Figueres,[87] but stuck to the idea of defending the city and entrusted García Oliver – who attended briefly – with this task.

[90] Having rejected plans to destroy all goods stored in harbour warehouses, the undersecretary for supplies Antonio Cordón decided to distribute foodstuffs among residents; the order was delayed by bombing raid of 45 German and Italian aircraft.

[101] In the early hours of January 24 Rojo issued his last defence orders, particularly anxious to prevent encirclement by Nationalist troops advancing north of Barcelona; this would cut off evacuation routes leading towards Girona.

Offices, shops, factories were either closed or empty; public transport including metro was not operating, shortages in electricity supply caused shutdown in entire quarters.

Magazines in the Barcelona harbour, warehouses and large storage deposits came first, then looting started to affect high street shops, cafeterias (all closed by the time), empty institutions or any places where robbers expected to find any valuables.

The usual booty in the city, which for months was suffering from food shortages and rationing, were foodstuffs: canned meat, chocolate, coffee, flour, oil, vinegar, sugar, beans and others, though people were seen carrying also rolls of textile, paper, domestic or office machinery and other goods.

In some spots small groups were loading items on makeshift vehicles hoping for late evacuation, in others rare patrols of armed men were walking in unclear direction, while single individuals with bags or cases on their backs, most likely booty from looting – were sneaking around.

[134] The political amalgam emergent in early Francoist Barcelona was dominated by a coalition of Falangists and generic right-wing politicians, including the conservatives and the monarchists;[135] the Carlists, who attempted to re-institutionalize their fairly strong pre-war network, were quickly marginalised by administrative means.

[140] The birth rate, which during the war declined from monthly average of 1.410 in 1936 to 1.133 in 1938, 937 in January 1939 and the record low of 597 in July 1939, recovered quickly; in February 1940 it was already 1.533 and kept growing; similar trend marked marriages.

Except some harbour facilities, heavily bombed by Nationalist aviation, the city infrastructure did not suffer major losses during the war; out of 60.000 buildings in the municipal inventory, only 3.000 were listed as damaged.

[162] Much effort was dedicated to restoration of churches, almost all damaged or otherwise vandalised, with priority given to the Catedral, la Sagrada Família, el Tibidabo and Pedralbes; in cases of totally destroyed temples, religious service was held in the open until full reconstruction.

Catalonia developed faster than other regions, e.g. Barcelona consistently consumed more cement - a usual indicator to measure dynamics of construction business - than Madrid or Valencia, and at times even twice as much.