Battle of Vukovar

[16] Following the death of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980, long-suppressed ethnic nationalism revived and the individual republics began to assert their authority more strongly as the federal government weakened.

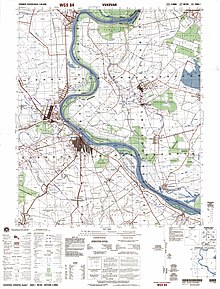

[30] Serb militias systematically blocked transport routes in the predominantly Serb-inhabited countryside around Vukovar, and within days the town could only be reached by an unpaved track running through Croat-inhabited villages.

[37][38] A Croatian government representative in Vukovar told the Zagreb authorities that "the city is again [the] victim of terror, armed strife and provocative shoot-outs with potentially unfathomable consequences.

Its head, General Veljko Kadijević, the Yugoslav Minister of Defence and a committed communist, initially sought to forcibly keep Yugoslavia together and proclaimed the army's neutrality in the Serb-Croat conflict.

The JNA did not intend to make Vukovar the main focus of the offensive, but as happened with Stalingrad in the Second World War, an initially inconsequential engagement became an essential political symbol for both sides.

[74] Croatian forces countered the JNA's attacks by mining approach roads, sending out mobile teams equipped with anti-tank weapons, deploying many snipers, and fighting back from heavily fortified positions.

[90] A JNA officer who served at Vukovar later described how his men refused to obey orders on several occasions, "abandoning combat vehicles, discarding weapons, gathering on some flat ground, sitting and singing Give Peace a Chance by John Lennon."

General Anton Tus, commander of the Croatian forces outside the Vukovar perimeter, put Dedaković in charge of a breakthrough operation to relieve the town and launched a counter-offensive on 13 October.

[97] During the battle's final phase, Vukovar's remaining inhabitants, including several thousand Serbs, took refuge in cellars and communal bomb shelters, which housed up to 700 people each.

Blaine Harden of The Washington Post wrote: Not one roof, door or wall in all of Vukovar seems to have escaped jagged gouges or gaping holes left by shrapnel, bullets, bombs or artillery shells – all delivered as part of a three-month effort by Serb insurgents and the Serb-led Yugoslav army to wrest the city from its Croatian defenders.

[112]Chuck Sudetic of The New York Times reported: Only soldiers of the Serbian-dominated army, stray dogs and a few journalists walked the smoky, rubble-choked streets amid the ruins of the apartment buildings, stores and hotel in Vukovar's center.

[124] In 1997, the journalist Miroslav Lazanski, who has close ties to the Serbian military, wrote in the Belgrade newspaper Večernje novosti that "on the side of the JNA, Territorial Defence and volunteer units, exactly 1,103 members were killed."

[131] The non-Serb population of the town and the surrounding region was systematically ethnically cleansed, and at least 20,000 of Vukovar's inhabitants were forced to leave, adding to the tens of thousands already expelled from across eastern Slavonia.

A JNA soldier who fought at Vukovar told the Serbian newspaper Dnevni Telegraf that "the Chetnik [paramilitaries] behaved like professional plunderers, they knew what to look for in the houses they looted.

[145] Three JNA officers – Mile Mrkšić, Veselin Šljivančanin and Miroslav Radić – were indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) on multiple counts of crimes against humanity and violations of the laws of war, having surrendered or been captured in 2002 and 2003.

[149] Serbian paramilitary leader Vojislav Šešelj was indicted on war crimes charges, including several counts of extermination, for the Vukovar hospital massacre, in which his "White Eagles" were allegedly involved.

[151] On 11 April 2018, the Appeals Chamber of the follow-up Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals convicted him of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 10 years' imprisonment for a speech delivered in May 1992 in which he called for the expulsion of Croats from Vojvodina.

[153] The Croatian Serb leader Goran Hadžić was indicted for "wanton destruction of homes, religious and cultural buildings" and "devastation not justified by military necessity" across eastern Slavonia, and for deporting Vukovar's non-Serb population.

The Croatian media described the Serbian forces as "Serb terrorists" and a "Serbo-Communist army of occupation" intent on crushing the thousand-year dream of an independent Croatia.

There were overt appeals to racial and gender prejudice, including claims that Croatian combatants had "put on female dress to escape from the town" and had recruited "black men".

According to Human Rights Watch, the bodies belonged to those who had died of their injuries at the hospital, whose staff had been prevented from burying them by the intense Serbian bombardment, and had been forced to leave them lying in the open.

The United Nations (UN) imposed an arms embargo on all of the Yugoslav republics in September 1991 under Security Council Resolution 713, but this was ineffective, in part because the JNA had no need to import weapons.

[179] When the surrender could no longer be denied, the two newspapers interpreted the loss as a demonstration of Croatian bravery and resistance, blaming the international community for not intervening to help Croatia.

[95] The Croatian government also suppressed an issue of the newspaper Slobodni tjednik that published a transcript of a telephone call from Vukovar, in which Dedaković had pleaded with an evasive Tuđman for military assistance.

The survivors, veterans and journalists wrote numerous memoirs, songs and testimonies about the battle and its symbolism, calling it variously "the phenomenon", "the pride", "the hell" and "the Croatian knight".

"[188] The Serbian geographer Jovan Ilić set out a vision for the future of the region, envisaging it being annexed to Serbia and its expelled Croatian population being replaced with Serbs from elsewhere in Croatia.

Desimir Tošić of the Democratic Party accused Milošević of "using the conflict to cling to power", and Vuk Drašković, the leader of the Serbian Renewal Movement, appealed to JNA soldiers to "pick up their guns and run".

The army's leaders realised that they had overestimated their ability to pursue operations against heavily defended urban targets, such as the strategic central Croatian town of Gospić, which the JNA assessed as potentially a "second Vukovar".

[208] After the Erdut Agreement was signed in 1995, the United Nations Transitional Authority for Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Sirmium (UNTAES) was established to enable the return of Croatian refugees and to prepare the region for reintegration into Croatia.

This represents the expulsion of the town's Croat inhabitants and involves a five-kilometre (3.1 mile) walk from the city's hospital to the Croatian Memorial Cemetery of Homeland War Victims.