Family in the Soviet Union

[1] According to the 1968 law "Principles of Legislation on Marriage and the Family of the USSR and the Union Republics", parents are "to raise their children in the spirit of the Moral Code of the Builder of Communism, to attend to their physical development and their instruction in and preparation for socially useful activity".

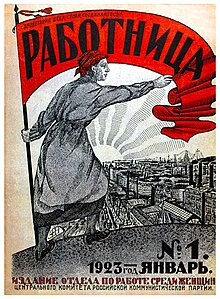

Prior to the 1917 revolution, women did not have equal rights to men and, since most of the population were peasants, they lived under the patriarchal village structure; they had to take care of the home as well as playing an important role in looking after farms.

[2] One of the main aims of the Lenin period was to abolish the bourgeois family, and free both men and women from the drudgery of housework.

Despite this strong push for change by the Zhenotdel, the immensely patriarchal society that had existed for hundreds of years prior, would supersede these efforts.

This left in unequal workload on the woman, who would also have a job outside of the home to help provide in a particularly difficult economy where food and adequate housing was often scarce.

The principals are: The nuclear family unit is an economic arrangement structured to maintain the ideological functions of Capitalism.

Goikhbarg considered the nuclear family unit to be a necessary but transitive social arrangement that would quickly be phased out by the growing communal resources of the state and would eventually "wither away".

The jurists intended for the code to provide a temporary legal framework to maintain protections for women and children until a system of total communal support could be established.

[6] Hundreds of thousands of unemployed women did not have registered marriages and were left with no means of support or protections following a divorce under the 1918 code.

This meant that women who ran the household and cared for the children would not be entitled to any material share of what the "provider" had brought to the marriage.

[6] With intentions similar to the legal recognition of de facto marriages, this new property law was a response to the lack of protections offered to women in the event of divorce.

[11] Additionally the code would do away with the 1918 concept of "collective paternity" where multiple men could be assigned to pay alimony if the father of a child could not be determined.

The jurists were not pursuing an ideological maneuver away from socialism, rather than taking more "temporary" measures to ensure the well-being of women and children since communal care had yet to materialize.

Insurance stipends, pregnancy leave, job security, light duty, child care services and payments for large families.

Citing the heavy manpower losses and social disruption following World War II, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet enacted laws that would further encourage marriage and childbirth.

[15] In the early 1920s, however, the weakening of family ties, combined with the devastation and dislocation caused by the Russian Civil War (1918–21), resulted in nearly 7 million homeless children.

This situation prompted senior Bolshevik Party officials to conclude that the State needed a more stable family life to rebuild the country's economy and shattered social structure.

In 1936 the government began to award payments to women with large families, banned abortions, and made divorces more difficult to obtain.

[15] Beginning in the mid-1980s, the government promoted family planning in order to slow the growth of the Central Asian indigenous populations.

For many years prior to the October Revolution, abortion was not uncommon in Russia, although it was illegal and carried a possible sentence of hard labor or exile.

Abortions were free for all women, although they were seen as a necessary evil due to economic hardship rather than a woman's right to control her own reproductive system.

This, along with stipends granted to recent mothers and bonuses given for women who bore many children, was part of an effort to combat the falling birthrate.

The younger and better educated Uzbeks and working women, however, were more likely to behave and think like their counterparts in the European areas of the Soviet Union, who tended to emphasize individual careers.

Various public institutions, for example, took responsibility for supporting individuals during times of sickness, incapacity, old age, maternity, and industrial injury.

State-run nurseries, preschools, schools, clubs, and youth organizations took over a great part of the family's role in socializing children.

[15] The transformation of the patriarchal, three-generation rural household to a modern, urban family of two adults and two children attests to the great changes that Soviet society had undergone since 1917.

[15] The history of the Soviet Union diet prior to World War II encompasses different periods that have varying influences on food production and availability.

The traditional types of food found in the Soviet Union were made up of various grains for breads and pastries, dairy products such as cheese and yogurt, and various meats such as pork, fish, beef and chicken.

[19] By 1940, certain products, such as vegetables, meat and grains, were less abundant than other forms of food due to the strain on resources and poor crop yields.

Soups and broths made of meats and vegetables when available, were common meals for the Soviet peasant family.