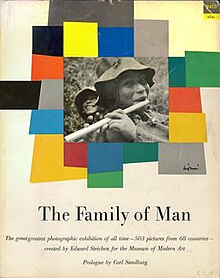

The Family of Man

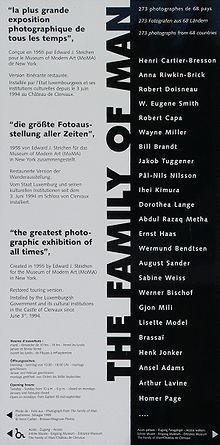

The Family of Man was an ambitious[1][2] exhibition of 503 photographs from 68 countries curated by Edward Steichen, the director of the New York City Museum of Modern Art's (MoMA) department of photography.

[9] The recently-formed United States Information Agency was instrumental in touring the photographs throughout the world in five different versions for seven years,[10] under the auspices of the Museum of Modern Art International Program.

This Moscow trade fair at Sokolniki Park was the scene of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and United States Vice President Richard Nixon's 'Kitchen Debate' over the relative merits of communism and capitalism.

Architect Paul Rudolph designed a series of temporary walls set amongst the existing structural columns,[20] which guided visitors past the images,[21] which he described as "telling a story",[22] encouraging them to pause at those that attracted their attention.

[15] Blown-up, often mural scale images, angled, floated or curved, some inset into other floor-to-ceiling prints, even displayed on the ceiling (a canted view of a silhouetted axeman and tree), on posts like finger-boards (in the final room), and the floor (for a Ring o' Roses series), were grouped together according to diverse themes.

Repeated prints of Eugene Harris' portrait of a Peruvian flute-player formed a coda, or acted as 'Pied Piper' to the audience, in the opinion of some reviewers,[23][25] and according to Steichen himself, expressed "a little bit of mischief, but much sweetness—that's the song of life.

Subjects then ranged in sequence from lovers, to childbirth, to household, and careers, then to death and, on a topical and portentous note, the hydrogen bomb (an image from LIFE magazine of the test detonation Mike, Operation Ivy, Enewetak Atoll, October 31, 1952) which was the only full-colour image; a room-filling backlit 1.8 m × 2.43 m (5.9 ft × 8.0 ft) Eastman transparency, replaced for the travelling version of the show with a different view of the same explosion in black and white.

[29] Carl Sandburg, Steichen's brother-in-law, 1951 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and known for his biography of Abraham Lincoln, inspired the title of the exhibition with a line from his poem The Long Shadow of Lincoln: A Litany (1944);[30]There is dust alive With dreams of the Republic, With dreams of the family of man Flung wide on a shrinking globe; It was Sandburg who added an accompanying poetic commentary also displayed as text panels throughout the exhibition and included in the publication, of which the following are samples; There is only one man in the world and his name is All Men.

Here are ironworkers, bridge men, musicians, sandhogs, miners, builders of huts and skyscrapers, jungle hunters, landlords, and the landless, the loved and the unloved, the lonely and abandoned, the brutal and the compassionate — one big family hugging close to the ball of Earth for its life and being.

Most images from the exhibition were reproduced with an introduction by Carl Sandburg, whose prologue reads, in part: The first cry of a baby in Chicago, or Zamboango, in Amsterdam or Rangoon, has the same pitch and key, each saying, "I am!

[37] In place of the huge colour transparency to which a space was devoted in the MoMA exhibition, and the black-and-white mural print that toured countries other than Japan, only this quotation of Bertrand Russell's anti-nuclear warning, in white type on a black page, appears in the book;[38] [...] The best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with hydrogen bombs is quite likely to put an end to the human race [...] There will be universal death — sudden for only a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

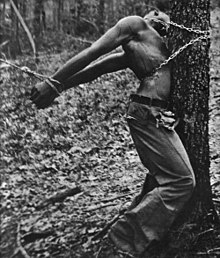

Absent also from the book, and removed by week eleven of the initial MoMA exhibition, was the distressing photograph of the aftermath of a lynching, of a dead young African American man, tied to a tree with his bound arms tautly tethered with a rope that stretches out of frame.

Steichen and his team drew heavily on Life archives for the photographs used in the final exhibition,[45] seventy-five by Abigail Solomon-Godeau's count, more than 20% of the total (111 out of 503), while some were obtained from other magazines; Vogue was represented by nine, Fortune (7), Argosy (seven, all by Homer Page), Ladies Home Journal (4); Popular Photography (3), and others Seventeen, Glamour, Harper's Bazaar, Time, the British Picture Post and the French Du, by one.

[47] The international tour of the definitive 1955 exhibition was sponsored by the now defunct United States Information Agency, whose aim was to counter Cold War propaganda by creating a better world image of American policies and values.

[46] The following lists notable participating photographers, excluding those with no professional or exhibiting history (see original 1955 MoMA checklist):[48] Photography, said Steichen, "communicates equally to everybody throughout the world.

In his book Mythologies, published in France a year after the exhibition in Paris in 1956, Barthes declared it to be a product of "conventional humanism," a collection of photographs in which everyone lives and "dies in the same way everywhere."

"[57] Some critics complained that Steichen merely transposed the magazine photo-essay from page to museum wall; in 1955 Rollie McKenna likened the experience to a ride through a funhouse,[58] while Russell Lynes in 1973 wrote that Family of Man "was a vast photo-essay, a literary formula basically, with much of the emotional and visual quality provided by sheer bigness of the blow-ups and its rather sententious message sharpened by juxtaposition of opposites — wheat fields and landscapes of boulders, peasants and patricians, a sort of 'look at all these nice folks in all these strange places who belong to this family.

Directly quoting Barthes, without acknowledgement,[29] she continues; "By purporting to show that individuals are born, work, laugh, and die everywhere in the same way, The Family of Man denies the determining weight of history - of genuine and historically embedded differences, injustices, and conflicts.

Sekula revises and expands this notion in relation to his ideas about economic globalisation in an article in October entitled "Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea: Rethinking the Traffic in Photographs".

[65] Others attacked the show as an attempt to paper over problems of race and class, including Christopher Phillips, John Berger, and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, who in her 2004 essay, while describing herself as among "those who intellectually came of age as postmodernists, poststructuralists, feminists, Marxists, antihumanists, or, for that matter, atheists, this little essay of Barthes's efficiently demonstrated the problem — indeed the bad faith — of sentimental humanism", concedes that "as photography exhibitions go, it is perhaps the ultimate "bad object" for progressives or critical theorists", but "good to think with".

A number of photographers and artists refer to their experience of The Family of Man exhibition or publication as formative or influential on them and some, including Australian Graham McCarter, being motivated by it to take up photography.

Racism, which in Steichen's show was represented by a lynching scene (replaced in the European showings by an enlargement of the famous picture of the Nuremberg trials), is confronted in the Weltausstellung der Fotografie section VIII "Das Missverständnis mit der Rasse" ('The Misunderstanding about Race') by the black man in the photograph by Gordon Parks who seems to view from his window two scenes of attacks on black people (photographed by Charles Moore).

The exhibition tour included the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), which at the time rarely showed photography, and her experience of installing it was in part the inspiration for Sue Davies to start The Photographers Gallery, London.

Independent curator Marvin Heiferman's The Family of Man 1955·1984 was a floor to ceiling collage of over 850 images and texts from magazines, newspapers and the art world shown in 1984 at PSI, The Institute for Art and Urban Resources Inc. (now MoMA PS1) Long Island City N.Y.[89] Abigail Solomon-Godeau described it as a reexamination of the themes of the 1955 show and critique of Steichen's arrangement of them into a "spectacle"; ...a grab bag of imagery and publicity ranging from baby food and sanitary napkin boxes to hard-core pornography, from detergent boxes to fashion photography, a cornucopia of consumer culture much of which, in one way or another, could be seen to engage the same themes purveyed in The Family of Man.

In the exhibit scenes of an endangered ecology and the threat to cultural identity in the global village predominate, but there are intimations that nature and love may prevail, despite everything artificial that surrounds it, notably so in family life.

In the catalogue, five authors; Ezra Stoller, Max Kozloff, Torsten Neuendorff, Bettina Allamoda and Jean Back analyse and comment on the historical model and twenty-two artists offer individual approaches around the following themes: Universalism/Separatism, Family/Anti-family, Individualisation, Common Strategies, Differences.

The works are predominantly from artist photographers rather than photojournalists; Bettina Allamoda, Aziz + Cucher, Los Carpinteros, Alfredo Jaar, Mike Kelley, Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, Lovett/Codagnone, Loring McAlpin, Christian Philipp Müller, Anna Petrie, Martha Rosler, Lisa Schmitz, Elaine Sturtevant, Mitra Tabizian and Andy Golding, Wolfgang Tillmans, Danny Tisdale, Lincoln Tobler, and David Wojnarowicz reflect major contemporary issues: identity, the information crisis, the illusion of leisure, and ethics.

[98] The show was devoted to invisible and minority figures, their demands for identity, and the possibility of reconfiguring a politics of representation to the ideal of giving a place to each member of the human community as represented in more than 200 emblematic photographs.

The works from the 1930s to 2016, drawn from the Cnap and Frac Aquitaine collections were selected on the principle of Roland Barthes' deconstruction identified by the curators in his Mythologies and in Camera Lucida, the latter being treated as a visual manifesto for minorities.

Texts by Pascal Beausse, Jacqueline Guittard, Claire Jacquet and Magali Nachtergael, Suejin Shin (Ilwoo Foundation) and Kyung-hwan Yeo (SeMA) were presented in a catalogue.