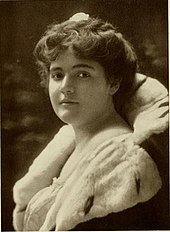

Fannie Hurst

Fannie Hurst (October 18, 1889 – February 23, 1968)[1] was an American novelist and short-story writer whose works were highly popular during the post-World War I era.

[2] Although her novels, including Lummox (1923), Back Street (1931), and Imitation of Life (1933), lost popularity over time and were mostly out of print as of the 2000s, they were bestsellers when first published and were translated into many languages.

In her last term in college, Hurst wrote the book and lyrics for a comic opera, The Official Chaperon, which was performed on the Washington University campus in June 1909.

During her early years in New York, she worked a variety of jobs: as a waitress at Childs and a sales clerk at Macy's, and acted in bit parts on Broadway.

In her spare time, Hurst attended night court sessions and visited Ellis Island and the slums, becoming in her own words "passionately anxious to awake in others a general sensitiveness to small people", and developing an awareness of "causes, including the lost and the threatened".

In 1912, after numerous rejections, Hurst finally published a story in The Saturday Evening Post, which shortly thereafter requested exclusive release of her future writings.

Early in Hurst's career, critics also considered her to be a serious artist, admiring her sensitive portrayals of immigrant life and urban "working girls".

Her second novel, Lummox (1923), about the tribulations of an oppressed domestic servant, was praised for its insights by Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

For decades, The New York Times continued to report regularly on Hurst's doings, including her walks in Central Park with her dogs, her travels abroad, her wardrobe, and the interior decoration of her apartment.

Its main character, a confident, independent young gentile woman, falls in love with a married Jewish banker and becomes his secret mistress, sacrificing her own life in the process and ultimately meeting a tragic end.

It told the story of two single mothers, one white and one African American, who become partners in a successful waffle and restaurant business (modeled after Quaker Oats Company's "Aunt Jemima" pancake mix) and have conflicts with their teenage daughters.

Hurst continued to write and publish until her death in 1968, although the commercial value of her work declined after World War II as popular tastes changed.

Throughout her life, Hurst was involved with many social activist groups supporting equal rights for women and African Americans, and occasionally assisting other people in need.

Hurst kept her maiden name and the couple maintained separate residences and arranged to renew their marriage contract every five years, if they both agreed to do so.

The revelation of the marriage in 1920 made national headlines, and The New York Times criticized the couple in an editorial for occupying two residences during a housing shortage.

[14] In 1958, Hurst published her autobiography, Anatomy of Me, which described many of her friendships and encounters with famous people of the era such as Theodore Dreiser and Eleanor Roosevelt.

She often dealt with subject matter considered "daringly frank and earthy" for its time, including unwed pregnancy, extramarital affairs, miscegnation, and homosexuality.

Hurst's work has been criticized for relying heavily on stereotypes, including "The Cad, the Alcoholic, the Egotist, the Self-Absorbed Rich Lady, the Golden-Hearted Whore, the Brave Wife, the Pure-Minded Virgin, and the Honest Burgher".

Hurst also focused on describing the "interior lives of women" and how the life choices of her female characters are driven by feelings and passions that they often cannot articulate or explain.

In 1964, Hurst established her archive at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin with the assistance of her friend, the noted civil rights lawyer Morris Ernst.

The collection of over 270 boxes includes extensive manuscripts of her works (short stories, novels, film scenarios, plays, articles, columns, speeches, and talks), both incoming and outgoing correspondence, notebooks, wills, contracts, interviews, and biographical material.

The universities used the money to endow professorships in their English departments and to create "Hurst Lounges" for writers to share their work with academics and students.

At the time of her death, and for several decades thereafter, Hurst was treated as a popular culture writer, credited with having "set the style followed by Jacqueline Susann, Judith Krantz, and Jackie Collins" and considered "one of the great trash novelists".

In 2004, The Feminist Press published a collection of her stories from the years 1912 to 1935, seeking to "propel a long overdue revival and reassessment of Hurst's work" and praising her "depth, intelligence, and artistry as a writer."

The theme song of the 1970 Mel Brooks comedy film The Twelve Chairs includes the lines, "Hope for the best, expect the worst/ You could be Tolstoy or Fannie Hurst."