Far Eastern Party

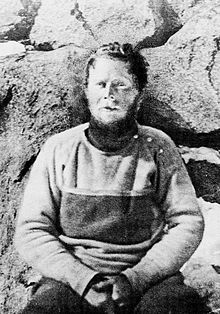

The Far Eastern Party was a sledging component of the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic expedition, which investigated the previously unexplored coastal regions of Antarctica west of Cape Adare.

Accompanying Mawson were Belgrave Edward Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz; the party used sledge dogs to increase their speed across the ice.

On 14 December 1912, with the party more than 311 miles (501 km) from the safety of the main base at Cape Denison, Ninnis and the sledge he was walking beside broke through the snow lid of a crevasse and were lost.

Their supplies now severely compromised, Mawson and Mertz turned back west, gradually shooting the remaining sledge dogs for food to supplement their scarce rations.

Mawson reached the comparative safety of Aladdin's Cave—a food depot five and a half miles (8.9 km) from the main base—on 1 February 1913, only to be trapped there for a week while a blizzard raged outside.

As a result, he missed the ship back to Australia; the SY Aurora had sailed on 8 February, just hours before his return to Cape Denison, after waiting for more than three weeks.

[2][nb 1] Battling katabatic winds that swept down from the Antarctic Plateau, the shore party erected their hut and began preparations for the following summer's sledging expeditions.

[2] The men readied clothing, sledges, tents and rations,[nb 2] conducted limited survey parties, and deployed several caches of supplies.

He hoped to travel about 500 miles (800 km) east, collecting geological data and specimens, mapping the coast, and claiming territory for the crown.

[11] Assisting him on this Far Eastern Party was Belgrave Edward Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and the Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz.

[nb 3][14][15] Each of the parties was required to return to Cape Denison by 15 January 1913, to allow time for the Aurora to collect them and escape Antarctic waters unencumbered by the winter sea ice.

"[17] Allowing Madigan and Stillwell's parties a head-start, Mawson, Ninnis, Mertz and the seventeen dogs left Cape Denison early in the afternoon, reaching Aladdin's Cave four hours later.

[nb 4][19] Heading south the following day to avoid crevasses to the east, they travelled about eight miles (13 km) before poor weather forced them to stop and camp.

Once at the bottom of the glacier they spent four days crossing fields of crevasses, battling strong winds and poor light that made navigation difficult.

[40] In the harsh conditions, the dogs began to grow restless; one of them, Shackleton, tore open the men's food bag and devoured a 2.5-pound (1.1 kg) pack of butter, crucial for their nourishment to supplement the hoosh.

[41] On 30 November, the party reached the eastern limit of the glacier and began the ascent to the plateau beyond, only to find themselves confronted at the top by sastrugi so sharp-edged the dogs were useless.

[42] Worse still, temperatures rose to 1 °C (34 °F), melting the snow and making pulling difficult; the party switched to travelling at night to avoid the worst of the conditions.

[43] From atop the ridge on the eastern side of the Ninnis Glacier, Mawson began to doubt the accuracy of the reports of land to the east by Charles Wilkes during the 1838–1842 United States Exploring Expedition.

The first option was to make for the coast, where they could supplement their meagre supplies with seal meat, and hope to meet with Madigan's party; that would considerably lengthen the journey, and the sea ice in summer could not be relied on.

Dragging Mertz's body in the sleeping bag from the tent, Mawson constructed a rough cairn from snow blocks to cover it, and used two spare beams from the sledge to form a cross, which he placed on the top.

[71] As the weather cleared on 11 January, Mawson continued west, estimating the distance back to Cape Denison at 100 miles (160 km).

The chance looked very small as the rope had sawed into the overhanging lid, my finger ends all damaged, myself weak ... With the feeling that Providence was helping me I made a great struggle, half getting out, then slipping back again several times, but at last just did it.

In it he found food and a note from Archibald Lang McLean, who along with Frank Hurley and Alfred Hodgeman had been sent out by Aurora's captain, John King Davis, to search for the Far Eastern Party.

Without them he could not hope to descend the steep ice slope to the hut, and so he began to fashion his own, collecting nails from every available source and hammering them into wood from spare packing cases.

The oncoming winter concerned Davis, and on 8 February—just hours before Mawson's return to the hut—the ship departed Commonwealth Bay, leaving six men behind as a relief party.

Upon Mawson's return, the Aurora was recalled by wireless radio, but powerful katabatic winds sweeping down from the plateau prevented the ship's boat from reaching the shore to collect the men.

[87] The delay may have saved Mawson's life; he later told Phillip Law, then-director of Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions, that he did not believe he could have survived the sea journey so soon after his ordeal.

"[97] In November 1913, shortly before the Aurora arrived to return them to Australia, the men remaining at Cape Denison erected a memorial cross for Mertz and Ninnis on Azimuth Hill to the north-west of the main hut.

A typical speaker stated that "Mawson has returned from a journey that was absolutely unparalleled in the history of exploration—one of the greatest illustrations of how the sternest affairs of Nature were overcome by the superb courage, power and resolve of man".

[104] The expedition was the first to use wireless radio in the Antarctic—transmitting back to Australia via a relay station established on Macquarie Island—and made several important scientific discoveries.