Faraday paradox

[2][3]This version of Faraday's law strictly holds only when the closed circuit is a loop of infinitely thin wire,[4] and is invalid in other circumstances.

(This step implicitly uses Gauss's law for magnetism: Since the flux lines have no beginning or end, they can only get into the loop by getting cut through by the wire.)

Putting these together, Meanwhile, EMF is defined as the energy available per unit charge that travels once around the wire loop.

[8] These paradoxes are generally resolved by the fact that an EMF may be created by a changing flux in a circuit as explained in Faraday's law or by the movement of a conductor in a magnetic field.

The disc and the magnet are fitted a short distance apart on the axle, on which they are free to rotate about their own axes of symmetry.

The discussion below shows this viewpoint stems from an incorrect choice of surface over which to calculate the flux.

In Faraday's model of electromagnetic induction, a circuit received an induced current when it cut lines of magnetic flux.

As is shown in the next section, modern physics (since the discovery of the electron) does not need the lines-of-flux picture and dispels the paradox.

If, on the other hand, one keep only one part of the rim from the radius junction to the brush, then the whole circuit is now a true loop whose shape varies with the time; then Faraday's law applies and leads to correct results.

If you hold the view that the field flux is a physical entity, it does rotate or depends on how it is generated.

Several experiments have been proposed using electrostatic measurements or electron beams to resolve the issue, but apparently none have been successfully performed to date.

A frame is set on a specific spacetime point, not an extending field or a flux line as a mathematical object.

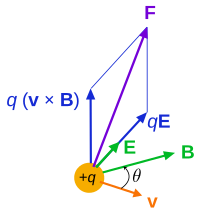

In Figure 1 this force (on a positive charge, not an electron) is outward toward the rim according to the right-hand rule.

Of course, this radial force, which is the cause of the current, creates a radial component of electron velocity, generating in turn its own Lorentz force component that opposes the circular motion of the electrons, tending to slow the disc's rotation, but the electrons retain a component of circular motion that continues to drive the current via the radial Lorentz force.

Mathematically, the law is stated: where ΦB is the flux, and dA is a vector element of area of a moving surface Σ(t) bounded by the loop around which the EMF is to be found.

The sign is chosen based upon Lenz's law: the field generated by the motion must oppose the change in flux caused by the rotation.

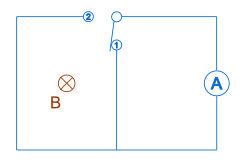

For example, the circuit with the radial segment in Figure 2 according to the right-hand rule adds to the applied B-field, tending to increase the flux linkage.

That suggests that the flux through this path is decreasing due to the rotation, so dθ / dt is negative.

In choosing the surface Σ(t), the restrictions are that (i) it has to be bounded by a closed curve around which the EMF is to be found, and (ii) it has to capture the relative motion of all moving parts of the circuit.

The flux is calculated though the entire path, return loop plus disc segment, and its rate-of change found.

To provide some intuition about this path independence, in Figure 3 the Faraday disc is unwrapped onto a strip, making it resemble a sliding rectangle problem.

Whether the magnet is "moving" is irrelevant in this analysis, due to the flux induced in the return path.

It is possible in principle to measure the distribution of charge, for example, through the electromotive force generated between the rim and the axle (though not necessarily easy).

In the case when the disk alone spins there is no change in flux through the circuit, however, there is an electromotive force induced contrary to Faraday's law.

However the galvanometer did not deflect meaning there was no induced voltage, and Faraday's law does not work in this case.

Nussbaum suggests that for Faraday's law to be valid, work must be done in producing the change in flux.

Meaning, Faraday's Law is only valid if work is performed in bringing about the change in flux.

A mathematical way to validate Faraday's Law in these kind of situations is to generalize the definition of EMF as in the proof of Faraday's law of induction: The galvanometer usually only measures the first term in the EMF which contributes the current in circuit, although sometimes it can measure the incorporation of the second term such as when the second term contributes part of the current which the galvanometer measures as motional EMF, e.g. in the Faraday's disk experiment.

However, Faraday's Law still holds since the apparent change of the magnetic flux goes to the second term in the above generalization of EMF.

After all, both/all these situations are consistent with the concern of relativity and microstructure of matter, and/or the completeness of Maxwell equation and Lorentz formula, or the combination of them, Hamiltonian mechanics.