Farthest South

From the late 19th century onward, the quest for Farthest South latitudes became a race to reach the pole, which culminated in Roald Amundsen's success in December 1911.

After such routes had been established and the main geographical features of the Earth had been broadly mapped, the lure for mercantile adventurers was the great fertile continent of "Terra Australis" which, according to myth, lay hidden in the south.

The British were pre-eminent in this endeavour, which was characterised by the rivalry between Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

[7][8][9][10] According to ancient legends, around the year 650 the Polynesian traveller Ui-te-Rangiora led a fleet of Waka Tīwai south until they reached "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea".

[12] Although Portuguese by birth, Ferdinand Magellan transferred his allegiance to King Charles I of Spain, on whose behalf he left Seville on 10 August 1519, with a squadron of five ships, in search of a western route to the Spice Islands in the East Indies.

[14] The first sighting of an ocean passage to the Pacific south of Tierra del Fuego is sometimes attributed to Francisco de Hoces of the Loaisa Expedition.

In January 1526, his ship San Lesmes was blown south from the Atlantic entrance of the Magellan Strait to a point where the crew thought they saw a headland, and water beyond it, which indicated the southern extremity of the continent.

[15] Sir Francis Drake sailed from Plymouth on 15 November 1577, in command of a fleet of five ships under his flagship Pelican, later renamed the Golden Hinde.

The Marigold was sunk by a giant wave; the Elizabeth managed to return into the Magellan Strait, later sailing eastwards back to England; the pinnace was lost later.

[16] On 14 June 1615, Willem Schouten, with two ships Eendracht and Hoorn, set sail from Texel in the Netherlands in search of a western route to the Pacific.

The Garcia de Nodal expedition discovered a small group of islands about 60 nautical miles (100 km; 70 mi) south-west of Cape Horn, at latitude 56°30'S.

[18] Other voyages brought further discoveries in the southern oceans; in August 1592, the English seaman John Davis had taken shelter "among certain Isles never before discovered"—presumed to be the Falkland Islands.

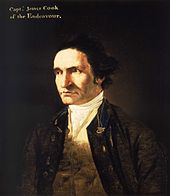

[20] The second of James Cook's historic voyages, 1772–1775, was primarily a search for the elusive Terra Australis Incognita that was still believed to lie somewhere in the unexplored latitudes below 40°S.

[24] This time Cook was able to penetrate deep beyond the Antarctic Circle, and on 30 January 1774 reached 71°10'S, his Farthest South,[25] but the state of the ice made further southward travel impossible.

[27] In the course of his voyages in Antarctic waters, Cook had encircled the world at latitudes generally above 60°S, and saw nothing but bleak inhospitable islands, without a hint of the fertile continent which some still hoped lay in the south.

[29] A few days before Bransfield's discovery, on 27 January 1820, the Russian captain Fabian von Bellingshausen, in another Antarctic sector, had come within sight of the coast of what is now known as Queen Maud Land.

[32] In 1822, Weddell, again in command of Jane and this time accompanied by a smaller ship, the cutter Beaufoy, set sail for the south with instructions from his employers that, should the sealing prove barren, he was to "investigate beyond the track of former navigators".

The expedition had first been proposed by leading astronomer Sir John Herschel, and was supported by the Royal Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

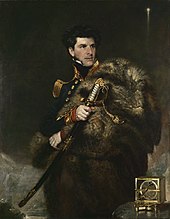

In his search for a strait or inlet, Ross explored 300 nautical miles (560 km; 350 mi) along the edge of the barrier, and reached an approximate latitude of 78°S on or about 8 February 1841.

The following season Ross returned and located an inlet in the Barrier face that enabled him, on 23 February 1842, to extend his Farthest South to 78°09'30"S,[41] a record which would remain unchallenged for 58 years.

Although Ross had not been able to land on the Antarctic continent, nor approach the location of the South Magnetic Pole, on his return to England in 1843 he was knighted for his achievements in geographical and scientific exploration.

[45] He followed this call with an appeal to British patriotism: "Is the last great piece of maritime exploration on the surface of our Earth to be undertaken by Britons, or is it to be left to those who may be destined to succeed or supplant us on the Ocean?

[48] The Norwegian-born Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink had emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked on survey teams in Queensland and New South Wales before accepting a school teaching post.

[57] The march continued, initially in favourable weather conditions,[58] but encountered increasing difficulties caused by the party's lack of ice travelling experience and the loss of all its dogs through a combination of poor diet and overwork.

[66][67] Shackleton's group continued southward, discovering and ascending the Beardmore Glacier to the polar plateau,[68] and then marching on to reach their Farthest South point at 88°23'S, a mere 97 nautical miles (180 km; 112 mi) from the pole, on 9 January 1909.

Here, they planted the Union Jack presented to them by Queen Alexandra, and took possession of the plateau in the name of King Edward VII,[69] before shortages of food and supplies forced them to turn back north.

[71] In the wake of Shackleton's near miss, Robert Scott organised the Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–1913, in which securing the South Pole for the British Empire was an explicitly stated prime objective.

[77] Avoiding the known route to the polar plateau via the Beardmore Glacier, Amundsen led his party of five due south, reaching the Transantarctic Mountains on 16 November.

[80] Since Cook's journeys, every expedition that had held the Farthest South record before Amundsen's conquest had been British; however, the final triumph indisputably belonged to the Norwegians.

[83] Dufek gave considerable assistance to the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955–1958, led by Vivian Fuchs, which on 19 January 1958, became the first party to reach the pole overland since Scott.