Time-lapse photography

Processes that would normally appear subtle and slow to the human eye, such as the motion of the sun and stars in the sky or the growth of a plant, become very pronounced.

The inception of time-lapse photography occurred in 1872 when Leland Stanford hired Eadweard Muybridge to prove whether or not race horses hooves ever are simultaneously in the air when running.

The experiments progressed for 6 years until 1878 when Muybridge set up a series of cameras for every few feet of a track which had tripwires the horses triggered as they ran.

[2] The first use of time-lapse photography in a feature film was in Georges Méliès' motion picture Carrefour De L'Opera (1897).

[5] Time-lapse photography of biological phenomena was pioneered by Jean Comandon in collaboration with Pathé Frères from 1909,[6][7] by F. Percy Smith in 1910 and Roman Vishniac from 1915 to 1918.

By using these techniques, Ott time-lapse animated plants "dancing" up and down synchronized to pre-recorded music tracks.

His cinematography of flowers blooming in such classic documentaries as Walt Disney's Secrets of Life (1956), pioneered the modern use of time-lapse on film and television.

[citation needed] Ott wrote several books on the history of his time-lapse adventures including My Ivory Cellar (1958) and Health and Light (1979), and produced the 1975 documentary film Exploring the Spectrum.

PBS's NOVA series aired a full episode on time-lapse (and slow motion) photography and systems in 1981 titled Moving Still.

Highlights of Oxford's work are slow-motion shots of a dog shaking water off himself, with close ups of drops knocking a bee off a flower, as well as a time-lapse sequence of the decay of a dead mouse.

In the late 1990s, Adam Zoghlin's time-lapse cinematography was featured in the CBS television series Early Edition, depicting the adventures of a character that receives tomorrow's newspaper today.

A man riding a bicycle will display legs pumping furiously while he flashes through city streets at the speed of a racing car.

Longer exposure rates for each frame can also produce blurs in the man's leg movements, heightening the illusion of speed.

Cinematographers refer to fast motion as undercranking since it was originally achieved by cranking a handcranked camera slower than normal.

Some intervalometers can be connected to motion control systems that move the camera on any number of axes as the time-lapse photography is achieved, creating tilts, pans, tracks, and trucking shots when the movie is played at normal frame rate.

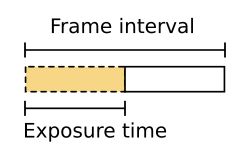

This relationship controls the amount of motion blur present in each frame and is, in principle, exactly the same as adjusting the shutter angle on a movie camera.

In time-lapse photography, the camera records images at a specific slow interval such as one frame every thirty seconds (1⁄30 fps).

Such a setup will create the effect of an extremely tight shutter angle giving the resulting film a stop-motion animation quality.

Director and cinematographer Ron Fricke designed his own motion control equipment that utilized stepper motors to pan, tilt and dolly the camera.

A panning time-lapse image can be easily and inexpensively achieved by using a widely available equatorial telescope mount with a right ascension motor.

The most classic example of this is the "slit-scan" opening of the "stargate" sequence toward the end of Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), created by Douglas Trumbull.

Three photographs are taken at separate exposure values (capturing the three in immediate succession) to produce a group of pictures for each frame representing the highlights, mid-tones, and shadows.

In the analog age, blending techniques have been used in order to handle this difference: One shot has been taken in daytime and the other one in the night from exactly the same camera angle.

Digital photography provides many ways to handle day-to-night transitions, such as automatic exposure and ISO, bulb ramping and several software solutions to operate the camera from a computer or smartphone.