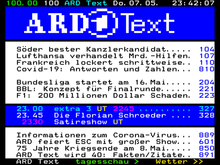

Teletext

[1][2] Teletext sends data in the broadcast signal, hidden in the invisible vertical blanking interval area at the top and bottom of the screen.

Most European teletext services continued to exist in one form or another until well into the 2000s when the expansion of the Internet precipitated a closure of some of them.

[17][18] The recent availability of digital television has led to more advanced systems being provided that perform the same task, such as MHEG-5 in the UK, and Multimedia Home Platform.

However, it was found that by combining even a slow data rate with a suitable memory, whole pages of information could be sent and stored on the TV for later recall.

[21] A major objective for Adams during the concept development stage was to make teletext affordable to the home user.

Meanwhile, the General Post Office (GPO), whose telecommunications division later became British Telecom, had been researching a similar concept since the late 1960s, known as Viewdata.

Unlike Teledata, a one-way service carried in the existing TV signal, Viewdata was a two-way system using telephones.

In 1972, the BBC demonstrated its system, now known as Ceefax ("seeing facts", the departmental stationery used the "Cx" logo), on various news shows.

Not to be outdone, the GPO immediately announced a 1200/75 baud videotext service under the name Prestel (this system was based on teletext protocols, but telephone-based).

The standard did not define the delivery system, so both Viewdata-like and Teledata-like services could at least share the TV-side hardware (which at that time was quite expensive).

The "Broadcast Teletext Specification" was published in September 1976 jointly by the IBA, the BBC and the British Radio Equipment Manufacturers' Association.

For example, state-owned RAI launched its teletext service, called Televideo,[25] in 1984, with support for Latin character set.

In France, where the SECAM standard is used in television broadcasting, a teletext system was developed in the late 1970s under the name Antiope.

Japan developed its own JTES[16] teletext system with support for Chinese, Katakana and Hiragana characters.

[28] The reason behind the replacement was that the original Cyclone system became harder to maintain over the years and the NOS even had to consult sometimes retired British teletext experts to deal with issues.

However, due to its broadcast nature, Teletext remained a reliable source of information during times of crisis, for example during the September 11 attacks when webpages of major news sites became inaccessible because of the high demand.

Teletext is also used for carrying special packets interpreted by TVs and video recorders, containing information about subjects such as channels and programming.

In the case of the Ceefax and ORACLE systems and their successors in the UK, the teletext signal is transmitted as part of the ordinary analog TV signal but concealed from view in the Vertical Blanking Interval (VBI) television lines which do not carry picture information.

Some pages, such as subtitles (closed captioning), are in-vision, meaning that text is displayed in a block on the screen covering part of the television image.

The proposed higher resolution Level 2 (1981) was not adopted in Britain (in-vision services from Ceefax & ORACLE did use it at various times, however, though even this was ceased by the BBC in 1996), although transmission rates were doubled from two to four lines a frame.

In the early 1980s, a number of higher extension levels were envisaged for the specification, based on ideas then being promoted for worldwide videotex standards (telephone dial-up services offering a similar mix of text and graphics).

After 1994 some stations adopted Level 2.5 Teletext or Hi-Text, which allows for a larger color palette and higher resolution graphics.

In addition to the UK version, several variants of the chip existed with slightly different character sets for particular localizations and/or languages.

With a suitable adapter, the computer could receive and display teletext pages, as well as software over the BBC's Ceefax service, for a time.

The Philips P2000 home computer's video logic was also based on a chip designed to provide teletext services on television sets.

In that way, two different users can be assigned the same page number at the same time as long as they do not receive the TV signals from the same source.

Spanish prisons have banned or deactivated TV sets with teletext capabilities, after finding that the inmates received coded messages from accomplices outside through the bulletin board sections.

Specific control commands can be used to switch between text and graphic pixels, and to add effects such as rasterization, blinking, or double line height.

This two-way nature allowed pages to be served on request, in contrast to the TV-based systems' sequential rolling method.

It consists only of 32 bits of data, primarily the date and time for which the broadcast of the currently running TV programme was originally scheduled.