Father Christmas

Although now known as a Christmas gift-bringer, and typically considered to be synonymous with Santa Claus, he was originally part of a much older and unrelated English folkloric tradition.

In 1572, the riding was suppressed on the orders of Edmund Grindal, the Archbishop of York (term 1570–1576), who complained of the "undecent and uncomely disguising" which drew multitudes of people from divine service.

[3] In his allegorical play Summer's Last Will and Testament,[7] written in about 1592, Thomas Nashe introduced for comic effect a miserly Christmas character who refuses to keep the feast.

[15] Its anonymous author, a parliamentarian, presents Father Christmas in a negative light, concentrating on his allegedly popish attributes: "For age, this hoarie headed man was of great yeares, and as white as snow; he entred the Romish Kallender time out of mind; [he] is old ...; he was full and fat as any dumb Docter of them all.

He got Prentises, Servants, and Schollars many play dayes, and therefore was well beloved by them also, and made all merry with Bagpipes, Fiddles, and other musicks, Giggs, Dances, and Mummings.

if at any time any have abused themselves by immoderate eating, and drinking or otherwise spoil the creatures, it is none of this old mans fault; neither ought he to suffer for it; for example the Sun and the Moon are by the heathens worship’d are they therefore bad because idolized?

The notion had a profound influence on the way that popular customs were seen, and most of the 19th century writers who bemoaned the state of contemporary Christmases were, at least to some extent, yearning for the mythical Merry England version.

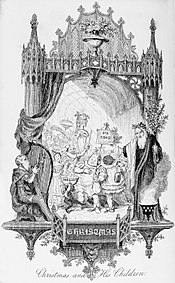

His children are identified as Roast Beef (Sir Loin) and his faithful squire or bottle-holder Plum Pudding; the slender figure of Wassail with her fount of perpetual youth; a 'tricksy spirit' who bears the bowl and is on the best of terms with the Turkey; Mumming; Misrule, with a feather in his cap; the Lord of Twelfth Night under a state-canopy of cake and wearing his ancient crown; Saint Distaff looking like an old maid ("she used to be a sad romp; but her merriest days we fear are over"); Carol singing; the Waits; and the twin-faced Janus.

[43] Hervey ends by lamenting the lost "uproarious merriment" of Christmas, and calls on his readers "who know anything of the 'old, old, very old, gray-bearded gentleman' or his family to aid us in our search after them; and with their good help we will endeavor to restore them to some portion of their ancient honors in England".

[46] Although not explicitly named Father Christmas, the character wears a holly wreath, is shown sitting among food, drink and wassail bowl, and is dressed in the traditional loose furred gown—but in green rather than the red that later become ubiquitous.

[48][49] One unusual portrayal (below centre) was described several times by William Sandys between 1830 and 1852, all in essentially the same terms:[32] "Father Christmas is represented as a grotesque old man, with a large mask and comic wig, and a huge club in his hand.

"[50] This representation is considered by the folklore scholar Peter Millington to be the result of the southern Father Christmas replacing the northern Beelzebub character in a hybrid play.

"[52] A mummers play mentioned in The Book of Days (1864) opened with "Old Father Christmas, bearing, as emblematic devices, the holly bough, wassail-bowl, &c".

In a Hampshire folk play of 1860 Father Christmas is portrayed as a disabled soldier: "[he] wore breeches and stockings, carried a begging-box, and conveyed himself upon two sticks; his arms were striped with chevrons like a noncommissioned officer.

Moore's poem became immensely popular[1] and Santa Claus customs, initially localized in the Dutch American areas, were becoming general in the United States by the middle of the century.

[48] The January 1848 edition of Howitt's Journal of Literature and Popular Progress, published in London, carried an illustrated article entitled "New Year's Eve in Different Nations".

This noted that one of the chief features of the American New Year's Eve was a custom carried over from the Dutch, namely the arrival of Santa Claus with gifts for the children.

"[61] In 1851 advertisements began appearing in Liverpool newspapers for a new transatlantic passenger service to and from New York aboard the Eagle Line's ship Santa Claus,[62] and returning visitors and emigrants to the British Isles on this and other vessels will have been familiar with the American figure.

"[70] Discussing the shops of Regent Street in London, another writer noted in December of that year, "you may fancy yourself in the abode of Father Christmas or St. Nicholas himself.

The young guests "tremblingly await the decision of the improvised Father Christmas, with his flowing grey beard, long robe, and slender staff".

[74] The first retail Christmas Grotto was set up in JR Robert's store in Stratford, London in December 1888,[73] and shopping arenas for children—often called 'Christmas Bazaars'—spread rapidly during the 1890s and 1900s, helping to assimilate Father Christmas/Santa Claus into society.

From the 1840s it had been accepted readily enough that presents were left for children by unseen hands overnight on Christmas Eve, but the receptacle was a matter of debate,[79] as was the nature of the visitor.

"[81] Before Santa Claus and the stocking became ubiquitous, one English tradition had been for fairies to visit on Christmas Eve to leave gifts in shoes set out in front of the fireplace.

In a short fantasy piece, the editor of the Cheltenham Chronicle in 1867 dreamt of being seized by the collar by Father Christmas, "rising up like a Geni of the Arabian Nights ... and moving rapidly through the aether".

[86] Folklorists and antiquarians were not, it seems, familiar with the new local customs and Ronald Hutton notes that in 1879 the newly formed Folk-Lore Society, ignorant of American practices, was still "excitedly trying to discover the source of the new belief".

[9] In January 1879 the antiquarian Edwin Lees wrote to Notes and Queries seeking information about an observance he had been told about by 'a country person': "On Christmas Eve, when the inmates of a house in the country retire to bed, all those desirous of a present place a stocking outside the door of their bedroom, with the expectation that some mythical being called Santiclaus will fill the stocking or place something within it before the morning.

[48][89] By the 1880s the American myth had become firmly established in the popular English imagination, the nocturnal visitor sometimes being known as Santa Claus and sometimes as Father Christmas (often complete with a hooded robe).

"[91] The commercial availability from 1895 of Tom Smith & Co's Santa Claus Surprise Stockings indicates how deeply the American myth had penetrated English society by the end of the century.

"[93] It took many years for authors and illustrators to agree that Father Christmas's costume should be portrayed as red—although that was always the most common colour—and he could sometimes be found in a gown of brown, green, blue or white.

In 1991, Raymond Briggs's two books were adapted as an animated short film, Father Christmas, starring Mel Smith as the voice of the title character.