Favela

[3] At the time, soldiers were brought from the War of Canudos, in the northeastern state of Bahia, to Rio de Janeiro and left with no place to live.

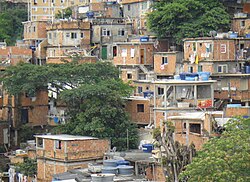

The explosive era of favela growth dates from the 1940s, when Getúlio Vargas's industrialization drive pulled hundreds of thousands of migrants into the former Federal District, to the 1970s, when shantytowns expanded beyond urban Rio and into the metropolitan periphery.

The change of Brazil's capital from Rio to Brasília in 1960 marked a slow but steady decline for the former, as industry and employment options began to dry up.

[citation needed] In the 1970s, Brazil's military dictatorship pioneered a favela eradication policy, which forced the displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents.

Changing routes of production and consumption meant that Rio de Janeiro found itself as a transit point for cocaine destined for Europe.

[13] Most of the current favelas greatly expanded in the 1970s, as a construction boom in the more affluent districts of Rio de Janeiro initiated a rural exodus of workers from poorer states in Brazil.

Because of crowding, unsanitary conditions, poor nutrition and pollution, disease is rampant in the poorer favelas and infant mortality rates are high.

The first wave of formal government intervention was in direct response to the overcrowding and outbreak of disease in Providência and the surrounding slums that had begun to appear through internal migration (Oliveira 1996).

During this period politicians, under the auspice of national industrialization and poverty alleviation, pushed for high density public housing as an alternative to the favelas (Skidmore 2010).

The military regime of the time provided limited resources to support the transition and favelados struggled to adapt to their new environments that were effectively ostracized communities of poorly built housing, inadequate infrastructure and lacking in public transport connections (Portes 1979).

Perlman (2006) points to the state's failure in appropriately managing the favelas as the main reason for the rampant violence, drugs and gang problems that ensued in the communities in the following years.

Stray-bullet killings, drug gangs and general violence were escalating in the favelas and from 1995 to mid-1995, the state approved a joint army-police intervention called "Operação Rio" (Human Rights Watch 1996).

Since 2009, Rio de Janeiro has had walls separating the rich neighborhoods from the favelas, officially to protect the natural environment, but critics charge that the barriers are for economic segregation.

The program was spearheaded by State Public Security Secretary José Mariano Beltrame with the backing of Rio Governor Sérgio Cabral.

Rio de Janeiro's state governor, Sérgio Cabral, traveled to Colombia in 2007 in order to observe public security improvements enacted in the country under Colombian President Álvaro Uribe since 2000.

The establishment of a UPP within a favela is initially spearheaded by Rio de Janeiro's elite police battalion, BOPE, in order to arrest or drive out gang leaders.

Rio's Security Chief, José Mariano Beltrame, has stated that the main purpose of the UPPs is more toward stopping armed men from ruling the streets than to put an end to drug trafficking.

Journalists within Rio studying ballot results from the 2012 municipal elections observed that those living within favelas administered by UPPs distributed their votes among a wider spectrum of candidates compared to areas controlled by drug lords or other organized crime groups such as milícias.

Seeking to build on 'Favela-Bairro', the informally coined 'Favela Chic' program was aimed at bringing favelas into the formal social fabric of the city while simultaneously empowering favelados to act as key agents in their communities (Navarro-Sertich 2011).

He points to the announcement in 2010 from Rio's Mayor Eduardo Paes concerning the removal of two inner city favelas, Morro de Prazeres and Laboriaux, and the forced relocation of its residents.

These favela eradication programs forcibly removed over 100,000 residents and placed them in public housing projects or back to the rural areas that many emigrated from.

For example: in Rio de Janeiro, the vast majority of the homeless population is black, and part of that can be attributed to favela gentrification and displacement of those in extreme poverty.

They do this by maintaining order in the favela and giving and receiving reciprocity and respect, thus creating an environment in which critical segments of the local population feel safe despite continuing high levels of violence.

Drug sales run rampant at night when many favelas host their own baile, or dance party, where many different social classes can be found.

These drug sales make up a business that in some of the occupied areas rakes in as much as US$150 million per month, according to official estimates released by the Rio media.

[29] These tours draw awareness to the needs of the underprivileged population living in these favelas, while giving tourists access to a side of Rio that often lurks in the shadows.

Tourists are given the opportunity to interact with local members of the community, leaders, and area officials, adding to their impressions of favela life.

The administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva initiated a program to further implement tourism into the structure of favela economies.

Beginning in Santa Marta, a favela of approximately 5,000 Cariocas, federal aid was administered in order to invigorate the tourism industry.

English signs indicating the location of attractions are posted throughout the community, samba schools are open, and viewing stations have been constructed so tourists can take advantage of Rio de Janeiro's vista.