Federal Radio Commission

In addition to increased regulatory powers, the FRC introduced the standard that, in order to receive a license, a radio station had to be shown to be "in the public interest, convenience, or necessity".

This law set up procedures for the Department of Commerce to license radio transmitters, which initially consisted primarily of maritime and amateur stations.

Herbert Hoover became the Secretary of Commerce in March 1921, and thus assumed primary responsibility for shaping radio broadcasting during its earliest days, which was a difficult task in a fast-changing environment.

To aid decision-making, he sponsored a series of four national conferences from 1922 to 1925, where invited industry leaders participated in setting standards for radio in general.

The Department of Commerce planned to request a review by the Supreme Court, but the case was rendered moot when Intercity decided to shut down the New York City station.

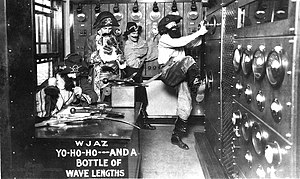

[6] Invoking the Intercity Radio Company case rulings, Zenith ignored the Commerce Department's order to return WJAZ to its assigned frequency.

McDonald expected a narrow ruling in his favor, claiming that only a small number of stations, including WJAZ, held the "Class D Developmental" licenses that were free from normal restrictions.

On April 16, 1926, Judge James H. Wilkerson's ruling stated that, under the 1912 Act, the Commerce Department in fact could not limit the number of broadcasting licenses issued, or designate station frequencies.

[7] The immediate result was that, until Congress passed new legislation, the Commerce Department could not limit the number of new broadcasting stations, which were now free to operate on any frequency and use any power they wished.

This effectively was granting established stations "property rights" in the use of their assignments, which the government wanted to avoid, because it generally considered the radio spectrum to be a public resource.

The legislation ultimately passed was known as the Dill-White Bill, which was proposed and sponsored by Senator Clarence Dill (D-Washington) and Representative Wallace H. White Jr. (R-Maine) on December 21, 1926.

It was brought to the Senate floor on January 28, 1927, and, as a compromise, specified that a five member commission would be given the power to reorganize radio regulation, but most of its duties would end after one year.

The FRC's commissioners, by zone, from 1927 to 1934 were: The five initial appointments, made by President Coolidge on March 2, 1927, were: Admiral William H. G. Bullard as chairman, Colonel John F. Dillon, Eugene O. Sykes, Henry A. Bellows, and Orestes H. Caldwell.

[10] It was not until March 1928, after Caldwell was approved by a one vote margin and Ira E. Robinson was appointed as chairman, that all five commissioner posts were filled with confirmed members.

The opening paragraph of the Radio Act of 1927 summarized its objectives as: "...this Act is intended to regulate all forms of interstate and foreign radio transmissions and communications within the United States, its Territories and possessions; to maintain the control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission; and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by individuals, firms, or corporations, for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal authority, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license.

[13] The FRC conducted a review and census of the existing stations, then notified them that if they wished to remain on the air they had to file a formal license application by January 15, 1928, as the first step in determining whether they met the new "public interest, convenience, or necessity" standard.

Although generally accepted as being successful on a technical level of reducing interference and improving reception, there was also a perception that large companies and their stations had received the best assignments.

Commissioner Ira E. Robinson publicly dissented, stating that: "Having opposed and voted against the plan and the allocations made thereunder, I deem it unethical and improper to take part in hearings for the modification of same".

[19] Most of the FRC decisions reviewed by the courts were upheld, however a notable exception involved WGY in Schenectady, New York, a long established high-powered station owned by General Electric.

"[22] Denied this station, Brinkley moved his operations to a series of powerful Mexican outlets located on the U.S. border, which helped to lead to implementation of the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement in 1941.

[23] Its programming was dominated by long denunciations made by pastor Robert "Fighting Bob" Shuler,[24] who stated that he operated the station in order to "make it hard for the bad man to do wrong in the community", but his strident broadcasts soon became very controversial.

[11] After a 1931 evaluation of the station's renewal application, chief examiner Ellis A. Yost expressed misgivings about Shuler's "extremely indiscreet" broadcasts, but recommended approval.

[26] The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia affirmed the Commission's decision and held that, despite First Amendment protections: "...this does not mean that the Government, through agencies established by Congress, may not refuse a renewal license to one who has abused it to broadcast defamatory and untrue matter.

[26] The court also ruled that denying license renewal as not in the public interest did not violate the Fifth Amendment's prohibition of "taking of property" without due process of law.

A prominent example under the FRC's jurisdiction occurred when a Gary, Indiana station, WJKS, proposed the deletion of its two timeshare partners, WIBO and WPCC, both located in Chicago, Illinois.

The law also transferred jurisdiction over communications common carriers, such as telephone and telegraph companies, from the Interstate Commerce Commission to the FCC.