Federal Reserve Act

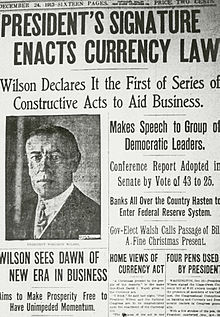

The Federal Reserve Act was passed by the 63rd United States Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913.

Wilson made the bill a top priority of his New Freedom domestic agenda, and he helped ensure that it passed both houses of Congress without major amendments.

A later amendment requires the Federal Reserve "to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates."

He argued that a central bank could bring order to the US monetary system, manage the government's revenues and payments, and provide credit to both the public and private sectors.

Included in a report of the Commission, submitted to Congress on January 9, 1912, were recommendations and draft legislation with 59 sections, for proposed changes in U.S. banking and currency laws.

The Plan called for the establishment of a National Reserve Association with 15 regional district branches and 46 geographically dispersed directors primarily from the banking profession.

[6] It is generally believed that the outline of the Plan had been formulated in a secret meeting on Jekyll Island in November 1910, which Aldrich and other well connected financiers attended.

[7] Since the Aldrich Plan gave too little power to the government, there was strong opposition to it from rural and western states because of fears that it would become a tool of bankers, specifically the Money Trust of New York City.

The platform also called for a systematic revision of banking laws in ways that would provide relief from financial panics, unemployment and business depression, and would protect the public from the "domination by what is known as the Money Trust."

The creation of congressionally authorized irredeemable currency by the Second Bank of the United States opened the door to the possibility of taxation by inflation.

In the aftermath of the Panic of 1907, there was general agreement among leaders in both parties of the necessity to create some sort of central banking system to provide coordination during financial emergencies.

Most leaders also sought currency reform, as they believed that the roughly $3.8 billion in coins and banknotes did not provide an adequate money supply during financial panics.

[12] Relying heavily on the advice of Louis Brandeis, Wilson sought a middle ground between progressives such as William Jennings Bryan and conservative Republicans like Aldrich.

Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters that the plan met their demands for an elastic currency because Federal Reserve notes would be obligations of the government.

[17] The Federal Reserve Act was amended in major ways over time, e.g. to account for Hawaii and Alaska's admission to the Union, for restructuring of the Fed's districts, and to specify jurisdictions.

[18] In June 1917 Congress passed major amendments to the Act in order to enable monetary expansion to cover the expected costs of World War I, which the US had just entered in April.

This relaxation de facto allowed less gold backing for each dollar note, and enabled the currency in circulation to more than double from $465m to $1247m just from June to December 1917.

"[22] The success of this amendment is notable, as in 1933, the US was in the throes of the Great Depression and public sentiment with regards to the Federal Reserve System and the banking community in general had significantly deteriorated.

Given the political climate, including of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and New Deal legislation, it is uncertain whether the Federal Reserve System would have survived.

On November 16, 1977, the Federal Reserve Act was amended to require the Board and the FOMC "to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates."

The Chairman was also required to appear before Congress at semi-annual hearings to report on the conduct of monetary policy, on economic development, and on the prospects for the future.

[citation needed] The passing of the Federal Reserve act of 1913 carried implications both domestically and internationally for the United States economic system.

[23] The absence of a central banking structure in the U.S. previous to this act left a financial essence that was characterized by immobile reserves and inelastic currency.

Opposition was based on protectionist sentiment; a central bank would serve a handful of financiers at the expense of small producers, businesses, farmers and consumers, and could destabilize the economy through speculation and inflation.

8, Clause 5, states: "The Congress shall have power To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures"), whether the structure of the federal reserve is transparent enough, whether the Federal Reserve is a public Cartel of private banks (also called a private banking cartel) established to protect powerful financial interests, fears of inflation, high government deficits, and whether the Federal Reserve's actions increased the severity of the Great Depression in the 1930s (and/or the severity or frequency of other boom-bust economic cycles, such as the late 2000s recession).