Federal Reserve Bank

Several policy questions have arisen with these institutions, including the degree of influence by private interests, the balancing of regional economic concerns, the prevention of financial panics, and the type of reserves used to back currency.

[2] A financial crisis known as the Panic of 1907 threatened several New York banks with failure, an outcome avoided through loans arranged by banker J. P. Morgan.

In response, Congress formed the National Monetary Commission to investigate options for providing currency and credit in future panics.

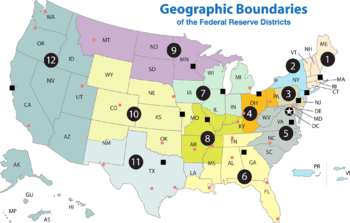

[4] The Reserve Banks are organized as self-financing corporations and empowered by Congress to distribute currency and regulate its value under policies set by the Federal Open Market Committee and the Board of Governors.

Legal cases involving the Federal Reserve Banks have concluded that they are "private", but can be held or deemed as "governmental" depending on the particular law at issue.

If a Reserve Bank were ever dissolved or liquidated, the Act states that members would be eligible to redeem their stock up to its purchase value, while any remaining surplus would belong to the federal government.

The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA) of 2008 additionally authorized the Reserve Banks to pay interest on member bank reserves, while the FAST Act of 2015 imposed an additional dividend limit equal to the yield determined in the most recent 10-year Treasury Note auction.

It manages the System Open Market Account (SOMA), a portfolio of government-issued or government-guaranteed securities that is shared among all of the Reserve Banks.

[13] The Federal Reserve Banks fund their own operations, primarily by distributing the earnings from the System Open Market Account.

Expenses and dividends paid are typically a small fraction of a Federal Reserve Bank's revenue each year.

This process connects the Reserve Banks' different functions – monetary policy, payment clearing and currency issue – as an integrated system.