Felice Beato

[7] In 1855 Felice Beato and Robertson travelled to Balaklava, Crimea, where they took over reportage of the Crimean War following Roger Fenton's departure.

[13] In February 1858 Beato arrived in Calcutta and began travelling throughout Northern India to document the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The two accompanied the Anglo-French forces travelling north to Talien Bay, then to Pehtang and the Taku Forts at the mouth of the Peiho, and on to Peking and Qingyi Yuan, the suburban Summer Palace.

[note 5] Beato's photographs of the Second Opium War are the first to document a military campaign as it unfolded,[23] doing so through a sequence of dated and related images.

Signor Beato was here in great excitement, characterising the group as 'beautiful,' and begging that it might not be interfered with until perpetuated by his photographic apparatus, which was done a few minutes afterwards.

On 18 and 19 October, the buildings were torched by the British First Division on the orders of Lord Elgin as a reprisal against the emperor for the torture and deaths of twenty members of an Allied diplomatic party.

[28] The two formed and maintained a partnership called "Beato & Wirgman, Artists and Photographers" during the years 1864–1867,[29] one of the earliest[30] and most important[16] commercial studios in Japan.

Accompanying ambassadorial delegations[32] and taking any other opportunities created by his personal popularity and close relationship with the British military, Beato reached areas of Japan where few westerners had ventured, and in addition to conventionally pleasing subjects sought sensational and macabre subject matter such as heads on display after decapitation.

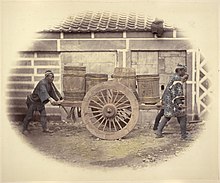

[35] Aside from the Portrait of Prince Kung, any appearances of Chinese people in Beato's earlier work had been peripheral (minor, blurred, or both) or as corpses.

With the exception of his work in September 1864 as an official photographer on the British military expedition to Shimonoseki,[28] Beato was eager to portray Japanese people, and did so uncondescendingly, even showing them as defiant in the face of the elevated status of westerners.

[40] By 1868 Beato had readied two volumes of photographs, "Native Types", containing 100 portraits and genre works, and "Views of Japan", containing 98 landscapes and cityscapes.

[41] Many of the photographs in Beato's albums were hand-coloured, a technique that in his studio successfully applied the refined skills of Japanese watercolourists and woodblock printmakers to European photography.

He owned land[49] and several studios, was a property consultant, had a financial interest in the Grand Hotel of Yokohama,[37] and was a dealer in imported carpets and women's bags, among other things.

[51] Following the sale to Stillfried & Andersen, Beato apparently retired for some years from photography, concentrating on his parallel career as a financial speculator and trader.

[54] Arriving in April 1885, however, he had missed the unsuccessful relief mission by three months and had to turn his attention to documenting the withdrawal of Wolseley's troops to the coastal town of Suakin.

Much publicity had been made in the British press about the three Anglo-Burmese Wars, which had started in 1825 and culminated in December 1885 with the fall of Mandalay and the capture of King Thibaw Min.

While he arrived in Burma after the main military operations ended, he would still get to see more of the action, as the annexation by the British led to an insurgency which lasted for the following decade.

This allowed Beato to take a number of pictures of the British military in operations or at the Royal Palace, Mandalay, as well as insurgency soldiers and prisoners.

Beato set up a photographic studio in Mandalay and, in 1894, a curiosa and antiques dealership, running both businesses separately and, according to records at the time, very successfully.

His past experience and the credibility derived from his time in Japan brought him a large clientele of opulent locals, posing in traditional attire for official portraits.

In 1896, Trench Gascoigne published some of Beato's images in Among Pagodas and Fair Ladies and, the following year, Mrs Ernest Hart's Picturesque Burma included more, while George W. Bird in his Wanderings in Burma not only presented thirty-five credited photographs but published a long description of Beato's businesses and recommended visitors to come by his shop.

In his old age, Beato had become an important business party in Colonial Burma, involved in many enterprises from electric works to life insurance and mining.

Whether acknowledged as his own work, sold as Stillfried & Andersen's, or encountered as anonymous engravings, Beato's work had a major impact: For over fifty years into the early twentieth century, Beato's photographs of Asia constituted the standard imagery of travel diaries, illustrated newspapers, and other published accounts, and thus helped shape "Western" notions of several Asian societies.

Throughout his career, Beato's work is marked by spectacular panoramas, which he produced by carefully making several contiguous exposures of a scene and then joining the resulting prints together, thereby re-creating the expansive view.