Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-born American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which he was an advocate of judicial restraint.

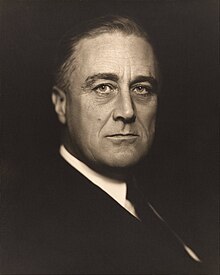

He became a friend and adviser of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed him to fill the Supreme Court vacancy caused by the death of Benjamin N. Cardozo.

Frankfurter wrote the Court's majority opinions in cases such as Minersville School District v. Gobitis, Gomillion v. Lightfoot, and Beauharnais v. Illinois.

He became lifelong friends with Walter Lippmann and Horace Kallen, became an editor of the Harvard Law Review, and graduated first in his class with one of the best academic records since Louis Brandeis.

His government position restricted his ability to publicly voice his Progressive views, though he expressed his opinions privately to friends such as Judge Learned Hand.

Among the disturbances he investigated were the 1916 Preparedness Day Bombing in San Francisco, where he argued strongly that the radical leader Thomas Mooney had been framed and required a new trial.

[26][27] Overall, Frankfurter's work gave him an opportunity to learn firsthand about labor politics and extremism, including anarchism, communism and revolutionary socialism.

He came to sympathize with labor issues, arguing that "unsatisfactory, remediable social conditions, if unattended, give rise to radical movements far transcending the original impulse."

[28] As the war drew to a close, Frankfurter was among the nearly one hundred intellectuals who signed a statement of principles for the formation of the League of Free Nations Associations, intended to increase United States participation in international affairs.

[10] Following the arrest of suspected communist radicals in 1919 and 1920 during the Palmer raids, Frankfurter, together with other prominent lawyers including Zechariah Chafee, signed an ACLU report which condemned the "utterly illegal acts committed by those charged with the highest duty of enforcing the laws" and noted they had committed entrapment, police brutality, prolonged incommunicado detention, and violations of due process in court.

When A. Lawrence Lowell, the President of Harvard University, proposed to limit the enrollment of Jewish students, Frankfurter worked with others to defeat the plan.

[28][38] In the late 1920s, he attracted public attention when he supported calls for a new trial for Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant anarchists who had been sentenced to death on robbery and murder charges.

Frankfurter wrote an influential article for The Atlantic Monthly and subsequently a book, The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti: A Critical Analysis for Lawyers and Laymen.

He critiqued the prosecution's case and the judge's handling of the trial; he asserted that the convictions were the result of anti-immigrant prejudice and enduring anti-radical hysteria of the Red Scare of 1919–20.

[41] He argued against the economic plans of Raymond Moley, Adolf Berle and Rexford Tugwell, while recognizing the need for major changes to deal with the inequalities of wealth distribution that had led to the devastating nature of the Great Depression.

"[46][47] Following the death of Supreme Court associate justice Benjamin N. Cardozo in July 1938, President Roosevelt turned to Frankfurter for recommendations of prospective candidates to fill the vacancy.

[56] In his judicial restraint philosophy, Frankfurter was strongly influenced by his close friend and mentor Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who had taken a firm stand during his tenure on the bench against the doctrine of "economic due process".

A frequent ally, Justice Robert H. Jackson, wrote the majority opinion in this case, which reversed the decision only three years prior in poetic passionate terms as a fundamental constitutional principle, that no government authority has the right to define official dogma and require its affirmation by citizens.

Frankfurter's extensive dissent began by raising and then rejecting the notion that as a Jew, he ought "to particularly protect minorities," although he did say that his personal political sympathies were with the majority opinion.

[61][62] But, in the Baker case, the majority of justices ruled to settle the matter – saying that the drawing of state legislative districts was within the purview of federal judges, despite Frankfurter's warnings that the Court should avoid entering "the political thicket".

"[64] He recognized that curtailing the free speech of those who advocate the overthrow of government by force also risked stifling criticism by those who did not, writing that "[it] is a sobering fact that in sustaining the convictions before us we can hardly escape restriction on the interchange of ideas.

The case was scheduled for re-argument when Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, whose crucial vote appeared to be opposed to overruling the pro-segregation precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson, died before the court's decision was made.

Frankfurter reportedly remarked that Vinson's death was the first solid piece of evidence he had seen to prove the existence of God, though some believe the story to be "possibly apocryphal".

[72] Later in his career, Frankfurter's judicial restraint philosophy frequently put him on the dissenting side of ground-breaking decisions taken by the Warren Court to end discrimination.

[76] Throughout his career on the court, Frankfurter was a large influence on many justices, such as Tom C. Clark, Harold Hitz Burton, Charles Evans Whittaker, and Sherman Minton.

[83] Frankfurter was in his time the leader of the conservative faction of the Supreme Court; he would for many years feud with liberals such as justices Hugo Black and William O.

[85] Douglas, Murphy, and then Rutledge were the first justices to agree with Hugo Black's notion that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the Bill of Rights protection into it; this view would later mostly become law, during the period of the Warren Court.

"[54] In the Court's biweekly conference sessions, traditionally a period for vote-counting, Frankfurter had the habit of lecturing his colleagues for forty-five minutes at a time or more with his book resting on a podium.

[92] However, Frankfurter's influence over other justices was limited by his failure to adapt to new surroundings, his style of personal relations (relying heavily on the use of flattery and ingratiation, which ultimately proved divisive), and his strict adherence to the ideology of judicial restraint.

However, in 1972 it was discovered that more than a thousand pages of his archives, including his correspondence with Lyndon B. Johnson and others, had been stolen from the Library of Congress; the crime remains unsolved and the perpetrator and motive are unknown.