Felix Mendelssohn

His sister Fanny Mendelssohn received a similar musical education and was a talented composer and pianist in her own right; some of her early songs were published under her brother's name and her Easter Sonata was for a time mistakenly attributed to him after being lost and rediscovered in the 1970s.

Mendelssohn enjoyed early success in Germany, and revived interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, notably with his performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829.

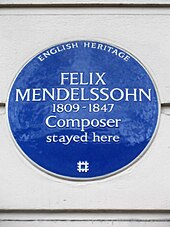

He became well received in his travels throughout Europe as a composer, conductor and soloist; his ten visits to Britain – during which many of his major works were premiered – form an important part of his adult career.

[8] The family moved to Berlin in 1811, leaving Hamburg in disguise in fear of French reprisal for the Mendelssohn bank's role in breaking Napoleon's Continental System blockade.

Frequent visitors to the salon organised by his parents at their home in Berlin included artists, musicians and scientists, among them Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt, and the mathematician Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet (whom Mendelssohn's sister Rebecka would later marry).

[15] In an 1829 letter to Felix, Abraham explained that adopting the Bartholdy name was meant to demonstrate a decisive break with the traditions of his father Moses: "There can no more be a Christian Mendelssohn than there can be a Jewish Confucius".

[16] On embarking on his musical career, Felix did not entirely drop the name Mendelssohn as Abraham had requested, but in deference to his father signed his letters and had his visiting cards printed using the form 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'.

[34][n 5] This translation also qualified Mendelssohn to study at the University of Berlin, where from 1826 to 1829 he attended lectures on aesthetics by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, on history by Eduard Gans, and on geography by Carl Ritter.

[47] In the spring of that year Mendelssohn directed the Lower Rhenish Music Festival in Düsseldorf, beginning with a performance of George Frideric Handel's oratorio Israel in Egypt prepared from the original score, which he had found in London.

[53] A landmark event during Mendelssohn's Leipzig years was the premiere of his oratorio Paulus, (the English version of this is known as St. Paul), given at the Lower Rhenish Festival in Düsseldorf in 1836, shortly after the death of the composer's father, which affected him greatly; Felix wrote that he would "never cease to endeavour to gain his approval ... although I can no longer enjoy it".

[61] He made ten visits to Britain, lasting altogether about 20 months; he won a strong following, which enabled him to make a good impression on British musical life.

[67] On Mendelssohn's eighth British visit in the summer of 1844, he conducted five of the Philharmonic concerts in London, and wrote: "[N]ever before was anything like this season – we never went to bed before half-past one, every hour of every day was filled with engagements three weeks beforehand, and I got through more music in two months than in all the rest of the year."

"[79] While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy, and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer's death,[80] this was misleading.

The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's.

The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state".

[88] Felix was notably reluctant, either in his letters or conversation, to comment on his innermost beliefs; his friend Devrient wrote that "[his] deep convictions were never uttered in intercourse with the world; only in rare and intimate moments did they ever appear, and then only in the slightest and most humorous allusions".

He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but in his letters expresses his frank disapproval of their works, for example writing of Liszt that his compositions were "inferior to his playing, and […] only calculated for virtuosos";[92] of Berlioz's overture Les francs-juges "[T]he orchestration is such a frightful muddle [...] that one ought to wash one's hands after handling one of his scores";[93] and of Meyerbeer's opera Robert le diable "I consider it ignoble", calling its villain Bertram "a poor devil".

[100] The family papers inherited by Marie's and Lili's children form the basis of the extensive collection of Mendelssohn manuscripts, including the so-called "Green Books" of his correspondence, now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

[107] In 1847, Mendelssohn attended a London performance of Meyerbeer's Robert le diable – an opera that musically he despised – in order to hear Lind's British debut, in the role of Alice.

"[114] This approach was recognized by Mendelssohn himself, who wrote that, in his meetings with Goethe, he gave the poet "historical exhibitions" at the keyboard; "every morning, for about an hour, I have to play a variety of works by great composers in chronological order, and must explain to him how they contributed to the advance of music.

"[113] The musicologist Greg Vitercik considers that, while "Mendelssohn's music only rarely aspires to provoke", the stylistic innovations evident from his earliest works solve some of the contradictions between classical forms and the sentiments of Romanticism.

[123] These four works show an intuitive command of form, harmony, counterpoint, colour, and compositional technique, which in the opinion of R. Larry Todd justifies claims frequently made that Mendelssohn's precocity exceeded even that of Mozart in its intellectual grasp.

He visited Fingal's Cave, on the Hebridean isle of Staffa, as part of his Grand Tour of Europe, and was so impressed that he scribbled the opening theme of the overture on the spot, including it in a letter he wrote home the same evening.

1 in D minor, Mendelssohn uncharacteristically took the advice of his fellow composer, Ferdinand Hiller, and rewrote the piano part in a more Romantic, "Schumannesque" style, considerably heightening its effect.

[146] Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words (Lieder ohne Worte), eight cycles each containing six lyric pieces (two published posthumously), remain his most famous solo piano compositions.

[40] 1829 saw Die Heimkehr aus der Fremde (Son and Stranger or Return of the Roamer), a comedy of mistaken identity written in honour of his parents' silver anniversary and unpublished during his lifetime.

[152] Although he never abandoned the idea of composing a full opera, and considered many subjects – including that of the Nibelung saga later adapted by Wagner, about which he corresponded with his sister Fanny[153] – he never wrote more than a few pages of sketches for any project.

[156] Strikingly different is the more overtly Romantic Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night), a setting for chorus and orchestra of a ballad by Goethe describing pagan rituals of the Druids in the Harz mountains in the early days of Christianity.

One of his obituarists noted: "First and chiefest we esteem his pianoforte-playing, with its amazing elasticity of touch, rapidity, and power; next his scientific and vigorous organ playing [...] his triumphs on these instruments are fresh in public recollection.

[188] In the 20th century the Nazi regime and its Reichsmusikkammer cited Mendelssohn's Jewish origin in banning performance and publication of his works, even asking Nazi-approved composers to rewrite incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream (Carl Orff obliged).