Feminism in Latin America

[3] Latin American feminism exists in the context of centuries of colonialism, the transportation and subjugation of slaves from Africa, and the mistreatment of native people.

With various regions in Latin America and the Caribbean, the definition of feminism varies across different groups where there has been cultural, political, and social involvement.

The expression of diversity and change from the viewpoint of those who have historically been marginalized, particularly through the experiences of colonialism and patriarchy has consistently been a focus of feminist philosophy in Latin America.

For example, a woman would know what issues impact them more than a man would), regarding how most Latina feminist philosophers enjoy a cultural and economic privilege that distances them from the living conditions of the majority of Latin American women.

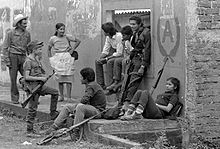

[6] There is a fairly solid consensus among academics and activists that women's participation in leftist movements has been one of the central reasons for the development of Latin American feminism.

However, there has been resistance to including the viewpoints of excluded groups, especially in relation to race, class, and sexuality, inside the mainstream feminist movement.

The two groups have brought up major concerns regarding liberal feminism's flaws especially its tendency to overlook racial, class, and colonial issues.

History has both vilified and glorified Manuela Sáenz - for her affair with Simon Bolivar, and for accusations that say she only “manipulated gender norms to advance her person and political interests.” As an early supporter of the independence cause, she spied on Spanish royalty and held intellectual gatherings called tertulias.

Similar to Sáenz, Gorriti held tertulias for literary men and women, one of whom was Clorinda Matto de Turner, a novelist sympathetic towards Indians and critical of the priesthood in Peru.

[citation needed] A prominent international figure born during this time was Gabriela Mistral, who in 1945 won the Nobel prize in literature and became a voice for women in Latin America.

The suffragists were not happy with the little progress, but this partial action allowed the PNR to seem in favor of suffrage without running the risk of electoral consequences.

Marìa del Refugio “Cuca” Garcìa's, had to negotiate state and local power institutions that operated somewhat independently of Mexico City as part of her challenge to national political authority.

Historian Alan Knight pointed out that despite the revolutionary government's promotion of "effective suffrage," elections frequently lacked democratic integrity, showing the absence of an identifiable feeling of civic duty in politics during the 1930s.

As Gloria Anzaldúa said, we must put history “through a sieve, winnow out the lies, look at the forces that we as a race, as women, have been part of.” [16] Such female groups arose amid the sharp radicalization of class struggles in the continent, which resulted in labor and mass rising.

Slogans, such as “Women give life, the dictatorships exterminates it,” “In the Day of the National Protest: Let’s make love not the beds,” and “Feminism is Liberty, Socialism, and Much More,” portrayed the demands of many Latin American feminists.

[19] Gloria Anzaldúa, of Indigenous descent, described her experience with intersectionality as a “racial, ideological, cultural, and biological crosspollination” and called it a “new mestiza consciousness.” [16] Various critiques of “internal colonialism of Latin American states toward their own indigenous populations” and “Eurocentrism in the social sciences” emerged, giving rise to Latin American Feminist Theory.

These movements organized to denounce the torture, disappearances, and crimes of the dictatorship, were headed mainly by women (mothers, grandmothers and widows).

In order to understand the change in the language of feminist movements, it is necessary to bear in mind two things: the first is that it was women that headed revelations and subsequent struggle for the punishment of those who were responsible for the state terrorism, and the second is the policy-especially of the United States- to prioritize human rights in the international agenda.

[9] Scholars argue that there is a strong correlation between the improvement of legal rights for Latin American women and the country's struggle for democracy.

It is important to note though, that the advance of Latin American women's legal equality does not get rid of the social and economic inequality present.

The more professional tactics of NGOs and political lobbying have given Latina feminists more influence on public policy, but at the cost of giving up “bolder, more innovative proposals from community initiatives.

Leaders such as Rafael de la Dehesa have contributed to describing early LGBT relations in parts of Latin America through his writings and advocacy.

Rafael has also introduced the idea of normalizing LGBT issues in patriarchal conservative societies such as Mexico and Brazil to suggest that being gay should no longer be considered taboo in the early 2000s.

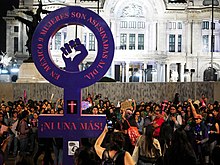

As a powerful response to gender-based violence, the Ni Una Menos campaign has grown to represent a larger fight for women's rights across the area.

The Mayan women that live in Guatemala and parts of southern Mexico, for example, have struggled to gain any political mobility over the last few years due to immigration crises, and economic and educational disadvantages.

[36][37] In the late 1990s, Shayne traveled to Cuba and interviewed Maria Antonia Figuero: she and her mother had worked alongside Castro during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista.

These gatherings were not only unique to Chile, but were found throughout Latin America - Bogota, Colombia (1981), Lima, Perú (1983), Bertioga, Brazil (1985), Taxco, Mexico (1987), and San Bernardo, Argentina (1990) - through the 1980s known as Encuentros.

[39] Some issues of great concern include: voluntary maternity/responsible paternity, divorce law reform, equal pay, personal autonomy, challenging the consistently negative and sexist portrayal of women in the media, access to formal political representation.

[41] Latina suffragists were innovative women who established the foundation for the diverse, intersectional activism that Latin American feminists continue to take part in today.

de Lopez, a high school teacher, was the first person in the state of California to give speeches in support of women's suffrage in Spanish.