Feminism in Russia

In the 20th century Russian feminists, inspired by socialism, shifted their focus from philanthropic works to labor organizing among peasants and factory workers.

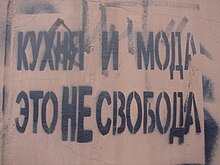

[2] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, feminist circles arose among the intelligentsia, although the term continues to carry negative connotations among contemporary Russians.

[3] Russian feminism originated in the 18th century, influenced by the Western European Enlightenment and the prominent role of women as a symbol for democracy and freedom in the French Revolution.

The male Decembrists were a group of aristocratic revolutionaries who in 1825 were convicted of plotting to overthrow Emperor Nicholas I, and many of whom were sentenced to serve in labor camps in Siberia.

Though the wives, sisters, and mothers of the Decembrist men shared the same liberal democratic political views as their male relatives, they were not charged with treason, because they were women; however, 11 of them, including Sheremeteva and Princess Mariya Volkonskaya, still chose to accompany their husbands, brothers, and sons to the labor camps.

Together with Maria Trubnikova, Nadezhda Stasova and Evgenia Konradi, she lobbied the Emperor to create and fund higher education courses for women.

[14] Demonstrating "considerable skill in rallying popular support", according to the historian Christine Johanson, the women wrote a carefully-worded petition to Tsar Alexander II.

[16] He rejected the petition in late 1868, but allowed mixed-gender public lectures which women could attend, under pressure from the Tsar (then Alexander II).

[16] The triumvirate also appealed to war minister Dmitry Milyutin, who agreed to host the courses after being persuaded by his wife, daughter, and Filosofova.

However, as part of Konstantin Pobedonostsev's efforts to bring educational institutions under government control, Stasova was forced to step down as director, officially accused of "inefficiency and muddleheadedness".

In his later years, Leo Tolstoy argued against the traditional institution of marriage, comparing it to forced prostitution and slavery, a theme that he also touched on in his novel Anna Karenina.

[17] In his plays and short stories, Anton Chekhov portrayed a variety of working female protagonists, from actresses to governesses, who sacrificed social esteem and affluence for the sake of financial and personal independence; in spite of this sacrifice, these women are among the few Chekhovian characters who are truly satisfied with their lives.

[18] In his influential 1863 novel What is to be Done?, the writer Nikolai Chernyshevski embodied the new feminist ideas in the novel's heroine, Vera Pavlovna, who dreams of a future utopian society with perfect equality among the sexes.

[20] Vladimir Lenin, who led the Bolsheviks to power in the October Revolution, recognized the importance of women's equality in the Soviet Union (USSR) they established.

"To effect [woman's] emancipation and make her the equal of man," he wrote in 1919, two years after the Revolution, following the Marxist theories that underlaid Soviet communism, "it is necessary to be socialized and for women to participate in common productive labor.

"A man can fool around with other women, drink, even be lackadaisical toward his job, and this is generally forgiven," wrote Hedrick Smith, former Russian correspondent for The New York Times, but "if a woman does the same things, she is criticized for taking a light-hearted approach toward her marriage and her work.

"[29] In an open letter to the country's leadership shortly before he was expelled from it in 1974, the dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn talked about an alleged heavy burden placed on women to do the menial work in Soviet society: "How can one fail to feel shame and compassion at the sight of our women carrying heavy barrows of stones for paving the street?

[failed verification][citation needed] Yet, sociological studies at the time found that Soviet women tended not to see their inequality as a problem.

Citizens of the Soviet Union could file complaints and receive redress through the Communist Party, but the post-Soviet government had not developed systems of state recourse.

During glasnost and after the fall of the Soviet Union, feminist circles began to emerge among intelligentsia women in major cultural centers like Moscow and St.

From this struggle emerged female communities which empowered many women to assert themselves in their pursuit of work, equitable treatment and political voice.

However, Larisa Pavlova, the lawyer representing the Church, insisted this view "does not correspond with reality" and called feminism a "mortal sin".

[43] In 2022, Feminist Anti-War Resistance launched itself with a manifesto opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[44] and organizing a symbolic laying of flowers at Soviet war memorials on International Women's Day.