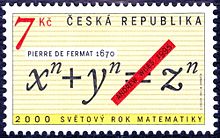

Fermat's Last Theorem

Attempts to prove it prompted substantial development in number theory, and over time Fermat's Last Theorem gained prominence as an unsolved problem in mathematics.

[6] Separately, around 1955, Japanese mathematicians Goro Shimura and Yutaka Taniyama suspected a link might exist between elliptic curves and modular forms, two completely different areas of mathematics.

[2] These papers by Frey, Serre and Ribet showed that if the Taniyama–Shimura conjecture could be proven for at least the semi-stable class of elliptic curves, a proof of Fermat's Last Theorem would also follow automatically.

Unlike Fermat's Last Theorem, the Taniyama–Shimura conjecture was a major active research area and viewed as more within reach of contemporary mathematics.

A flaw was discovered in one part of his original paper during peer review and required a further year and collaboration with a past student, Richard Taylor, to resolve.

The remaining parts of the Taniyama–Shimura–Weil conjecture, now proven and known as the modularity theorem, were subsequently proved by other mathematicians, who built on Wiles's work between 1996 and 2001.

As described above, the discovery of this equivalent statement was crucial to the eventual solution of Fermat's Last Theorem, as it provided a means by which it could be "attacked" for all numbers at once.

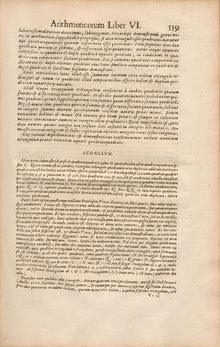

Alternative proofs of the case n = 4 were developed later[45] by Frénicle de Bessy (1676),[46] Leonhard Euler (1738),[47] Kausler (1802),[48] Peter Barlow (1811),[49] Adrien-Marie Legendre (1830),[50] Schopis (1825),[51] Olry Terquem (1846),[52] Joseph Bertrand (1851),[53] Victor Lebesgue (1853, 1859, 1862),[54] Théophile Pépin (1883),[55] Tafelmacher (1893),[56] David Hilbert (1897),[57] Bendz (1901),[58] Gambioli (1901),[59] Leopold Kronecker (1901),[60] Bang (1905),[61] Sommer (1907),[62] Bottari (1908),[63] Karel Rychlík (1910),[64] Nutzhorn (1912),[65] Robert Carmichael (1913),[66] Hancock (1931),[67] Gheorghe Vrănceanu (1966),[68] Grant and Perella (1999),[69] Barbara (2007),[70] and Dolan (2011).

[71] After Fermat proved the special case n = 4, the general proof for all n required only that the theorem be established for all odd prime exponents.

[44][80][81] Independent proofs were published[82] by Kausler (1802),[48] Legendre (1823, 1830),[50][83] Calzolari (1855),[84] Gabriel Lamé (1865),[85] Peter Guthrie Tait (1872),[86] Siegmund Günther (1878),[87] Gambioli (1901),[59] Krey (1909),[88] Rychlík (1910),[64] Stockhaus (1910),[89] Carmichael (1915),[90] Johannes van der Corput (1915),[91] Axel Thue (1917),[92] and Duarte (1944).

[123] Since they became ever more complicated as p increased, it seemed unlikely that the general case of Fermat's Last Theorem could be proved by building upon the proofs for individual exponents.

She also worked to set lower limits on the size of solutions to Fermat's equation for a given exponent p, a modified version of which was published by Adrien-Marie Legendre.

[129] In 1985, Leonard Adleman, Roger Heath-Brown and Étienne Fouvry proved that the first case of Fermat's Last Theorem holds for infinitely many odd primes p.[130] In 1847, Gabriel Lamé outlined a proof of Fermat's Last Theorem based on factoring the equation xp + yp = zp in complex numbers, specifically the cyclotomic field based on the roots of the number 1.

This gap was pointed out immediately by Joseph Liouville, who later read a paper that demonstrated this failure of unique factorisation, written by Ernst Kummer.

Kummer set himself the task of determining whether the cyclotomic field could be generalized to include new prime numbers such that unique factorisation was restored.

Using the general approach outlined by Lamé, Kummer proved both cases of Fermat's Last Theorem for all regular prime numbers.

In the 1920s, Louis Mordell posed a conjecture that implied that Fermat's equation has at most a finite number of nontrivial primitive integer solutions, if the exponent n is greater than two.

Around 1955, Japanese mathematicians Goro Shimura and Yutaka Taniyama observed a possible link between two apparently completely distinct branches of mathematics, elliptic curves and modular forms.

If Fermat's equation had any solution (a, b, c) for exponent p > 2, then it could be shown that the semi-stable elliptic curve (now known as a Frey-Hellegouarch[note 3]) would have such unusual properties that it was unlikely to be modular.

[137]: 259–260 [144][145] In response, he approached colleagues to seek out any hints of cutting-edge research and new techniques, and discovered an Euler system recently developed by Victor Kolyvagin and Matthias Flach that seemed "tailor made" for the inductive part of his proof.

Since his work relied extensively on this approach, which was new to mathematics and to Wiles, in January 1993 he asked his Princeton colleague, Nick Katz, to help him check his reasoning for subtle errors.

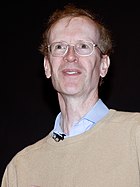

[155] Wiles states that on the morning of 19 September 1994, he was on the verge of giving up and was almost resigned to accepting that he had failed, and to publishing his work so that others could build on it and fix the error.

Nothing I ever do again will mean as much.On 24 October 1994, Wiles submitted two manuscripts, "Modular elliptic curves and Fermat's Last Theorem"[158][159] and "Ring theoretic properties of certain Hecke algebras",[160] the second of which was co-authored with Taylor and proved that certain conditions were met that were needed to justify the corrected step in the main paper.

For the Diophantine equation an/m + bn/m = cn/m with n not equal to 1, Bennett, Glass, and Székely proved in 2004 for n > 2, that if n and m are coprime, then there are integer solutions if and only if 6 divides m, and a1/m, b1/m, and c1/m are different complex 6th roots of the same real number.

[179][180] In 1857, the academy awarded 3,000 francs and a gold medal to Kummer for his research on ideal numbers, although he had not submitted an entry for the prize.

[181] In 1908, the German industrialist and amateur mathematician Paul Wolfskehl bequeathed 100,000 gold marks—a large sum at the time—to the Göttingen Academy of Sciences to offer as a prize for a complete proof of Fermat's Last Theorem.

[185] In March 2016, Wiles was awarded the Norwegian government's Abel prize worth €600,000 for "his stunning proof of Fermat's Last Theorem by way of the modularity conjecture for semistable elliptic curves, opening a new era in number theory".

According to some claims, Edmund Landau tended to use a special preprinted form for such proofs, where the location of the first mistake was left blank to be filled by one of his graduate students.

[188] According to F. Schlichting, a Wolfskehl reviewer, most of the proofs were based on elementary methods taught in schools, and often submitted by "people with a technical education but a failed career".

The popularity of the theorem outside science has led to it being described as achieving "that rarest of mathematical accolades: A niche role in pop culture.